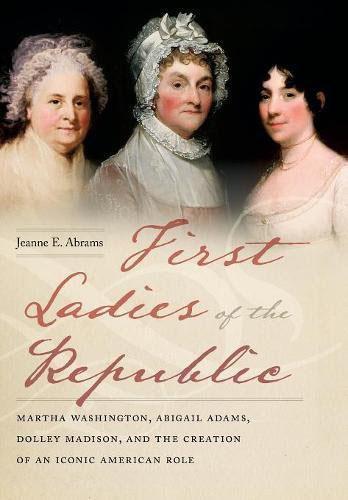

In the early days of the republic, it wasn’t clear what the wife of the president should be called. Sometimes it was “The Presidentess” or “Mrs. President.” Martha Washington was often referred to as “Lady Washington.” Like her husband George, she had to navigate a brand new role. Historian Jeanne Abrams from The University of Denver has written "First Ladies of the Republic," a new book about Martha Washington, Abigail Adams, and Dolley Madison. Abrams tells Colorado Matters what it was like to be one of the first, first ladies at a time when women couldn't vote and largely stayed out of politics.

Excerpt: "First Ladies of the Republic"

PROLOGUE When George Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States on April 30, 1789, King George III and Queen Charlotte occupied the throne in Great Britain. Queen Charlotte had been raised as a princess in a small German duchy, and the proposed royal union was cemented only after intense secret negotiations. Charlotte met her future husband just hours before their evening wedding at the Chapel Royal in St. James’s Palace in London on September 8, 1761, and she spoke no English at the time. The English-born George was the heir to the Hanoverian royal line and ascended to the throne in 1760 at the age of twenty-two. Yet, despite their exceedingly short acquaintance prior to their marriage, by all accounts they shared many mutual interests, led a relatively simple lifestyle compared to earlier British monarchs, and before the development of George’s mental illness, their amiable and long union resulted in fifteen children, thirteen who survived to adulthood. For their official coronation at London’s Westminster Abbey, just two weeks after their marriage, the English royal couple had been decked out in elaborate costumes, and the event followed intricate ceremonial rituals that had been developed over centuries. The coronation reflected the pomp, splendor, and opulence that had long characterized the investiture of European crowned heads of state, and it was witnessed by a crowd made up of members of the British royalty and the aristocracy in resplendent dress. The new Queen Charlotte wore a lavishly decorated ermine-trimmed silver and gold embroidered gown, which was studded with diamonds, pearls “as big as Cherrys” and other priceless gems, and on her head rested a “Circlet of Gold adorned with Jewels.” The train of her dress was supported by a royal princess and sixteen barons held up a canopy over her head. In contrast, Washington’s wife Martha was still in Virginia at their Mount Vernon plantation home at the time of his far less ostentatious first-term inauguration, when he took the oath of office on the balcony of Federal Hall on April 30, 1789 in New York City. It was witnessed by members of Congress, marked by the ringing of church bells, and then cheered enthusiastically by a crowd of ordinary citizens, who had stood respectfully outside the building. George wore a simple but well-made brown suit of American broadcloth woven at the Hartford Woolen Mill in Connecticut. The buttons on the suit featured carved eagles, the symbol of the fledgling republic. Washington’s choice of dress was consciously made to reflect that he was a man of the people. And when they had wed over twenty years earlier in 1757 in a modest ceremony attended by family and friends at her home, Martha and George Washington entered into the marriage by mutual consent without the need for the outside official negotiations that characterized royal marriages. Although the Washingtons had never traveled to England, in his earlier years one of George’s highest aspirations had been to become a respected Englishman, one who reflected British values and displayed unwavering loyalty to the Crown. Washington had always been an avid reader, and as a young man, he had undoubtedly read popular newspaper and magazine accounts about King George’s coronation, so he was likely familiar with the rituals surrounding European royalty. And after his election as president, Washington had two close advisers at his side, both of whom had first-hand experience at the European courts. John Adams, the new vice president, had served as a United States emissary first to France, and then later to the English Court of St. James, and Thomas Jefferson, appointed the first secretary of state, had returned to America from Paris at the end of 1789, after having spent five years as the minister to France then under the reign of Louis XVI. When Martha later joined the newly elected president during May of 1789 in the young nation’s first capital of New York City, she arrived in an elegantly simple gown sewn from material made in America rather than a more fashionable European import. It was clearly a symbolic gesture made to convey the egalitarian underpinnings of the newly minted nation. As The Gazette, the local Federalist newspaper, approvingly noted, “She was clothed in the manufacture of our Country.” The glittering canopy at Queen Charlotte’s coronation was sewn of Cloth of Gold. As the original First Lady of the United States, as the position would later become known, Martha Washington had to create her new quasi- official role from whole cloth. Despite the fact that it was not an elected position, Martha, as well as her two successors, First Ladies Abigail Adams and Dolley Madison, would all come to symbolize the heart and character of their husbands’ administrations. Never officially authorized, nevertheless, the position became a highly influential role in American history. These three women were responsible for essentially creating the role of First Lady without a roadmap to follow. To do so, they often had to walk a social and political tightrope. None of the three could simply imitate the role of European queens, but instead had to construct a unique and distinctively American style as the partner of the young nation’s leading political figure, the President. |