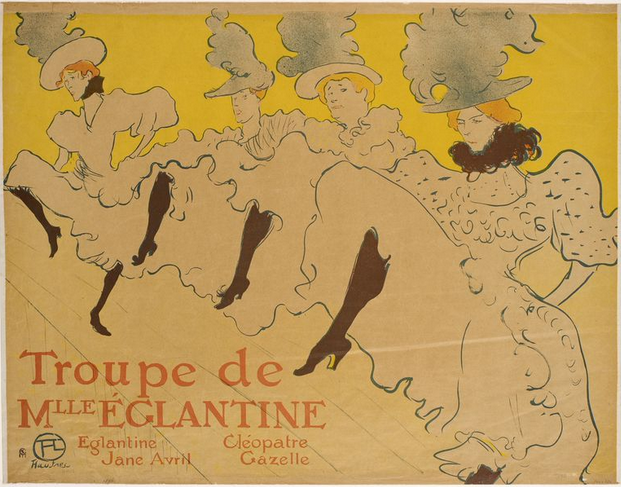

Showgirls in fishnet stockings and ruffled skirts kicking their legs to the sky flanked by musicians strumming their instruments. This is just some of the imagery captured in the artwork of French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Showgirls in fishnet stockings and ruffled skirts kicking their legs to the sky flanked by musicians strumming their instruments. This is just some of the imagery captured in the artwork of French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Toulouse-Lautrec's art is indicative of his time and, more specifically, of the artistic home he found in the bohemian neighborhood of Montmarte in Paris.

But the stories the artist tells of colorful people living seemingly glamorous and debaucherous lives continue to fascinate art lovers and influence other artists.

Starting this weekend, Toulouse-Lautrec's paintings, prints, drawings and posters will be on display at the Foothills Arts Center in Golden.

The exhibition, titled “Toulouse-Lautrec and La Vie Moderne: Paris 1880-1910," comes to Colorado after stints in Reno, Nevada and Columbus, Ohio. It encompasses an expansive array of Toulouse-Lautrec’s artwork as well as 100 other artists who worked and lived in Paris during the creative boom era of “La Belle Époque.”

The small Foothills Arts Center has pared down the large-scale exhibition to highlight three specific themes of this avant-garde artistic period: cabaret, circus and theater life in Paris as seen through the eyes of Toulouse-Lautrec, realist and naturalist art of the era as well as French symbolism.

Foothills Art Center curator Marianne Lorenz feels an affinity for Toulouse-Lautrec’s work. She says the artist's vibrant prints and paintings inspired her to become an art historian.

Lorenz talked to Colorado Public Radio about her museum’s upcoming exhibition and why Toulouse-Lautrec's style and voice continue to resonate with audiences today.

CPR: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was drawn to an area of Paris known as Montmartre, which was famous for its bohemian lifestyle and artistic cliques. How did Toulouse-Lautrec's environment influence his paintings, prints and illustrations?

Marianne Lorenz: It is important to remember that during Toulouse-Lautrec’s lifetime, Montmartre was a semi-rural working class district that was somewhat isolated from the rest of Paris. That isolation gave rise to a sub-culture that did not feel bound by the social and artistic conventions that characterized mainstream Paris. Artists and anarchists alike were drawn to Montmartre’s cheap rents, brothels and bawdy dance halls. Lautrec became acquainted with Montmartre because that is where his teacher, Fernand Cormon, had his studio and school. Lautrec began to do commercial work for some of the nightclubs and café-concerts in Montmartre that featured the dancers and patrons so often depicted in his lithographs and paintings. Lautrec was hired by the owners of cabarets such as the Chat Noir and the Divan Japonais to create advertising posters for their establishments. Those posters were intentionally simple and direct in their message and Lautrec’s talent was able to capture the personalities and atmosphere that characterized Montmartre’s nightlife.

CPR: Please highlight some of your favorite Toulouse-Lautrec pieces in the exhibition. Why do these works in particular stand out for you?

CPR: Please highlight some of your favorite Toulouse-Lautrec pieces in the exhibition. Why do these works in particular stand out for you?

Marianne Lorenz: There are two works in the exhibition that I feel capture not only life in Montmartre during the period, but also demonstrate the influence Toulouse-Lautrec had on later art. “Le Divan Japonais” really captures what was happening in Parisian artistic circles at the time. First, the name of the establishment reflects the interest European culture had in general for Japanese art and culture during the period. The angular composition and cropping of figures as well as the large areas of flat color reflect Toulouse-Lautrec’s careful study of Japanese woodblock prints. Finally, Toulouse-Lautrec included in this advertising poster three of the most popular and influential people of the time: the dancer Jane Avril, the performer Yvette Guilbert and the symbolist writer and critic Édouard Dujardin. The other work that stands out to me is Lautrec’s lithograph “May Milton” that was created for the English dancer’s American tour. The tour reportedly never actually took place and Milton left for the U.S. and was never heard from again. Critics of the period asserted that Milton was neither talented nor attractive. This print is especially interesting because it carries on the bottom right a "remarque" -- a small, personalized drawing or symbol that Toulouse-Lautrec added to a select number of the prints. In this case, Toulouse-Lautrec added a figure of a clown banjo player. This might be a personal reference to May Milton, whose face was described as looking clownish.

CPR: Toulouse-Lautrec's work is colorful and sometimes playful. How do these characteristics contribute to the longevity of his art?

Marianne Lorenz: Toulouse-Lautrec was above all else a modern artist. One can trace a line from his work all the way to the work of Andy Warhol and beyond. He was one of the first artists who understood that the boundaries between popular, or "low-brow" art, and academic, or "high-brow" art, were no longer clear. He fully utilized the new lithographic technology of his day and was able to transform simple advertising posters into influential and highly-collectible works of art. The artistic and cultural environment communicated through his paintings and prints no longer exists. But his unflinching, truthful exploration of that environment, and more importantly the people who created it and enjoyed it, continue to fascinate us today. Toulouse-Lautrec portrayed those who occupied the fringes of society -- the prostitutes and popular entertainers -- without judgment or comment. He told it like it was without moralizing, so we believe him. And because we believe him, he is important to us. Truth is timeless.

CPR: The exhibition is intended to be more than a showcase of Toulouse-Lautrec’s work, and is touted as an examination of the avant-garde movement in art. What can you share about some of the other artists whose work will be on display?

Marianne Lorenz: The exhibition has countless examples of the diversity and richness of the visual arts in France between 1880 and 1910. It begins with an exploration of the theater and cabaret world in Paris through the eyes of artists like Jules Chéret, Henri Riviere and Theophile-Alexandre Steinlen. We have one of the original “Tournée du Chat Noir” posters by Steinlen that took on a new cultural meaning in 2001 when it re-entered our consciousness in the crime scene photographs in the Michael Peterson murder trial. Peterson was a novelist convicted of murdering his second wife. There are numerous broadsides, theater posters, menus and brochure covers by artists like Pierre Bonnard, Edward Vuillard and Alfred Jarry. From there, the exhibition takes the visitor to landscapes, seascapes, portraits and still lifes by artists like Claude-Émile Schuffecker and Pierre-Georges Jeanniot. And visitors will be able to view a number of paintings that reveal the ideas and aspirations of the French Symbolist and Nabi movements.

CPR: Can you transport us back to Paris at the turn of the 19th century? What type of impact did this Bohemian Parisian era -- known as “La Belle Époque” -- have on art and culture, not just in France, but around the globe?

Marianne Lorenz: History has romanticized “La Belle Époque” in ways that would probably make it unrecognizable to the people who lived then. It was a period of great progress, which witnessed the emergence of a true middle-class consumer society and the beginnings of the emancipation of women. But it was also a time when an estimated 10 to 15 percent of the population suffered from syphilis with no cure in sight. Family visits to the viewing room at the Paris morgue on a Saturday afternoon were commonplace and anarchists carried out random assassinations on a regular basis. We also cannot forget the Dreyfus affair that revealed the anti-Semitic underpinnings of French institutions and divided French society. But the “Belle Époque” also gave us some of the most important symbols of modernity: the Paris metro, the Eiffel Tower, effective sewer systems and Louis Pasteur. Art Nouveau was the first great international art movement with centers not only in Paris, but also in Munich, Scotland, Vienna, Barcelona and Belgium. The social, cultural and aesthetic exchanges that occurred during the Belle Époque World Fairs in Paris in 1889 and 1900 created new, innovative exchanges among people of all cultures and backgrounds.

The “Toulouse-Lautrec and La Vie Moderne: Paris 1880-1910” exhibition runs June 7 through August 17 at the Foothills Art Center in Golden. For more information, visit FoothillsArtsCenter.org.