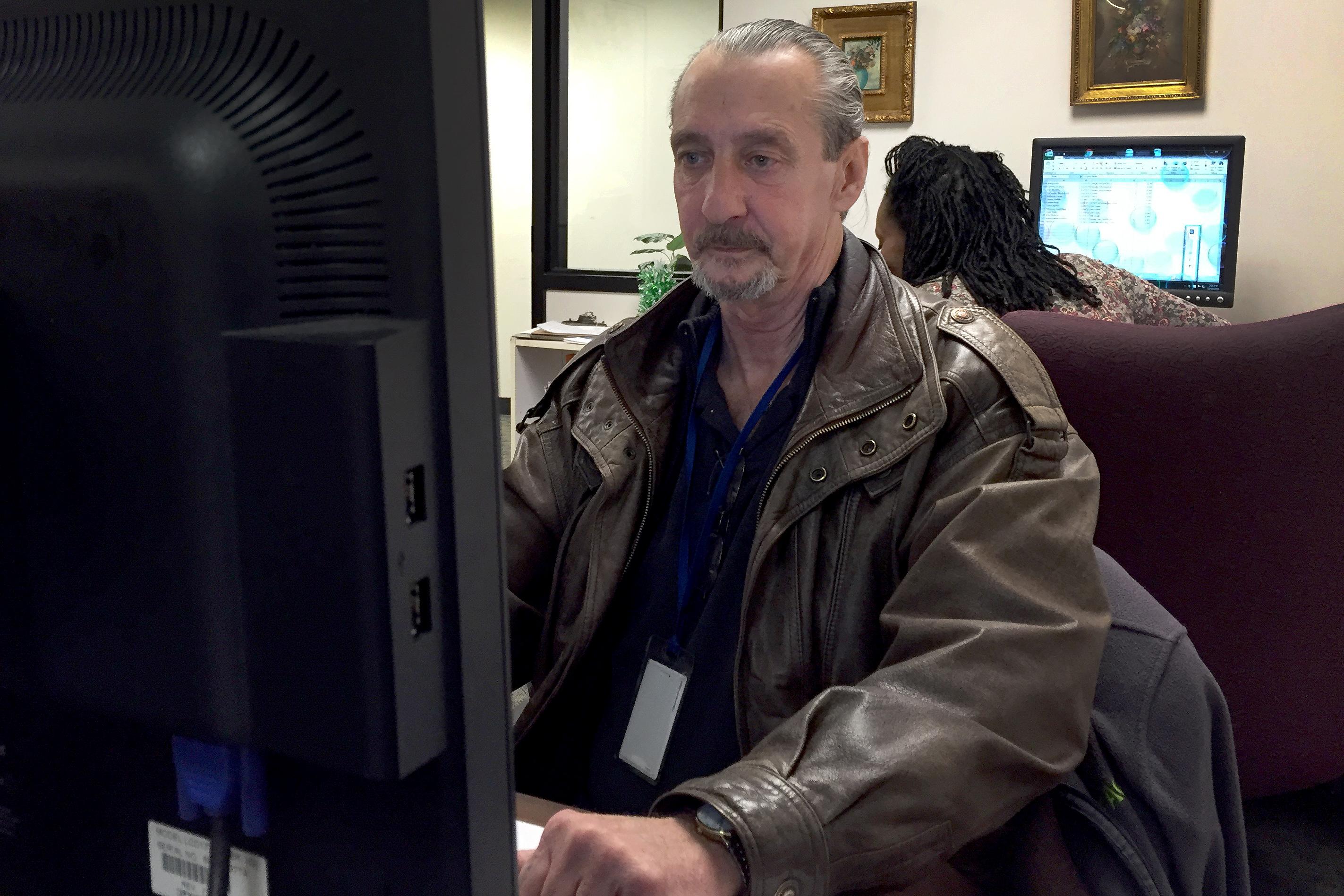

Robert Martinez is quite the popular guy at his office.

He works for AARP’s Senior Community Service Employment Program, which helps low-income seniors find jobs. And co-workers like Iola Washington rave about his work ethic and how nice of a guy he is.

“He’s a model to us and an inspiration,” she said.

Project director Sandra Wagner goes a step further.

“I trust him with my life,” she said.

Martinez shyly deflects the compliments.

“I’m not going to tell you how much I had to pay all these ladies to say these good things about me,” he said to laughter. “Unfortunately, I’m not going to have a paycheck coming.”

But there was a time when in Martinez’s life when few had anything good to say about him.

That was when the only thing he cared about was driving a needle full of heroin into his veins.

Martinez’s addiction drove him to a life of crime, which landed him in jail for 27 years after committing a string of armed robberies around Denver.

“I had never been a violent person,” he said. “But that drug addiction, boy, when that devil’s got you by the back of the hair, he’s not letting go. And you’re married to him.”

Although Martinez has since turned his life around, he initially found it difficult finding a job before coming to AARP. That’s a problem many people with criminal backgrounds face: They apply for work, but they just can’t get to the point of an interview because, if they're honest, they check the box on a job application that asks whether they have a criminal history.

Now, legislation is in the works that aims to remove that barrier. The movement behind it is being dubbed, “Ban the Box.” A bill expected to be introduced this session would make it illegal for many private sector employers to inquire about a person’s criminal background, prior to an interview being offered.

Supporters say that many employers who see the box checked disregard applicants before meeting them.

“What we hope to do is to allow these folks to have an opportunity to re-enter the workforce by at least being entitled to an interview before having a background check – which in many cases is often decades-old – held against them,” says Jack Regenbogen, an attorney with the Colorado Center on Law and Policy, a group that is backing the effort.

Martinez, who says he was rejected multiple times while looking for employment, believes the bill will do some good.

“Why is that box so intimidating? Because right away, it makes us feel that we are being set aside,” Martinez says. “If that box isn’t there maybe, just maybe, this employer is going to look at me and my qualifications. Not what I did in the past, but what I can do now.”

Extends Current Law

Colorado already has a law that prohibits asking that question on state government job applications. The bill as it's currently conceived would extend the prohibition to the private sector.

The bill would not prohibit employers from inquiring about a person’s criminal background. But it would postpone the background check until after an applicant has been offered an interview, according to a current bill draft.

The changes would not apply to employers who are required by law to consider an applicant’s criminal history.

If the bill passes, Colorado would join seven other states that have some sort of “ban the box” laws.

Supporters also argue that the more opportunities there are for people to find work, the less inclined they are to re-commit crimes.

Rep. Beth McCann, D-Denver, who expects to sponsor the bill, says the state’s “horrific recidivism rate” is affected when criminals re-offend out of frustration over not finding work.

“Are we really keeping the community safe by putting people in prison, but then when they get out, not providing them the opportunity to be productive?” McCann says.

That was the case for Martinez when he was released from prison in 2011. He applied for any kind of job he could find.

“Even shoveling snow,” he said. “My criminal background would not allow them to hire me. I was ready to throw the towel in. I was demoralized."

Martinez’s story is not unique, according to Regenbogen.

“I think that just really demonstrates how, in our state, these barriers to employment for people who are re-entering from the criminal justice system are particularly strong and difficult to overcome,” he said. “It’s heartbreaking, some of the stories I’ve heard since I started doing this work."

Opponents Say Legislation Is Unnecessary, Adds Costs

Business groups say the bill is unnecessary, and also believe that it would prevent employers from having all of the facts about an applicant when they’re deciding who to interview.

Tony Gagliardi, the Colorado state director of the National Federation of Independent Business, says the potential law change would slow the hiring process for small business owners looking to hire someone immediately. And he says a slower hiring process could mean added costs when employers have to pay overtime for workers filling in for positions left open.

Gagliardi also takes issue with the suggestion that employers would automatically disqualify an applicant based on one question on an application.

“I take exception to their assertion that businesses are just arbitrarily, the minute they see that box checked, throwing that application in the trash bag,” he said. “That’s an insult to my 700 members in Colorado.”

“Am I going to sit here and say it’s a perfect world? No, I’m not. Will this happen occasionally? Maybe. But nobody on the proponent’s side has ever shown one piece of empirical evidence that this happens. So, what they’re doing is trying to legislate to the exception rather than the rule," he said.

Jim Noon, president of Centennial Container, an east Denver-based cardboard box manufacturing and shipping supplies business, says the law wouldn’t affect him because he doesn’t ask about a person’s criminal history on his application.

“Someone here sorting boxes in the back and driving a forklift, whether they’ve spent time in jail or not, isn’t a problem,” he said. “And sometimes, I also don’t mind being the one to give someone a second chance.”

But Noon says he may testify against the legislation due to philosophical concerns.

“The policy side of me is totally against government banning what you can ask somebody,” he says. And he's unmoved by the argument that applications may end up in the trash, once an employer sees the box checked.

“Well, that’s totally up to them,” he said. “And I don’t think the government should be involved in telling them who they have to consider and how they have to consider.”

Gagliardi dismisses the effort as a “feel-good” piece of legislation that won’t solve anything.

“I think the question that needs to be asked is: What are our policy-makers doing for rehabilitative purposes if someone is incarcerated? Are they teaching the skills necessary, so when (prisoners) come out they have the skills they need to enter back in the workplace?” Gagliardi said.

“The answer is no. They are not doing enough. So, what they’re doing is shifting blame away from the public policy side of it to the small businesses,” he said.

But supporters like McCann say some people need help getting back on their feet.

“I believe that we as a society can do more to help folks find housing, find jobs, give them a chance after they’ve paid their debt,” she said.

Martinez agrees. The program that helped him get his job with AARP is ending soon. So, he’ll once again have to apply for jobs. But he has renewed hope this time.

“I have the confidence and the ability where I’ll get out there and I’ll pound those streets and I’ll get a job,” he said. “I don’t care if it’s shoveling manure. I will work. And so will a lot of other folks if you give them a chance.”

Martinez knows he’s made mistakes in the past, but he’s proud of how he’s turned his life around.

“I know I’m a better person, and I want to be that better person,” he said. “And, my God… I look in the mirror and I like myself. I like that man.”