Denver could be the future home of a new museum devoted to the recipients of the Medal of Honor.

The National Medal of Honor Museum Foundation was in Denver this week to meet with media, government, transportation officials and members of the Downtown Denver Partnership to present its ideas for the project.

“Whether your politics are on the left or right, the idea of building a National Medal of Honor museum that celebrates those that have earned the highest award, our nation's highest award for valor in combat, that's objectively a good thing,” foundation CEO Joe Daniels told CPR News Wednesday morning.

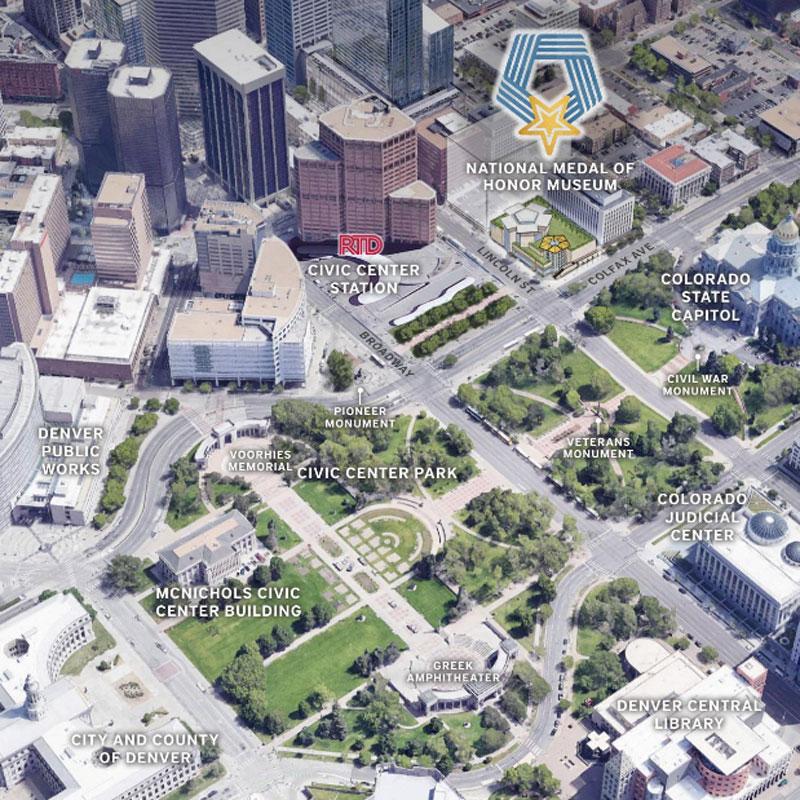

Denver and Arlington, Texas, are the two cities the foundation is considering. They plan to go to Texas in about a week to speak with officials and media there. If the museum were to land here, officials have their eye on two parcels in Denver’s Civic Center.

One of the plots is a 20,000 square-foot piece of land south of the Civic Center bus station. The museum hopes to build a gateway park there and approached the Regional Transportation District. But at a meeting Tuesday night, RTD’s board indicated they would not lease the real estate to the museum for their requested amount of $1 a year.

Daniels said this will be “an ongoing conversation” with RTD.

“I think that when we're able to sit down and talk with our government partners about how special would be for this city to play a role in building America's next national treasure, there's generally been a lot of enthusiasm,” he said.

The other plot of land, on the west corner of Colfax and Lincoln, is owned by the state.

Daniels appeared optimistic about Denver as a prospect, adding that the city hits a lot of the major factors the foundation seeks: a philanthropic market, available land, a sizable tourism market and “the sort of cultural mindset, the embracing of patriotism.”

A Big Ticket Project

The proposed museum will cost roughly $150 million. The city and state would need to contribute 10 to 20 percent of the cost and the foundation expects to make up the rest from private gifts.

Daniels, who was formerly the CEO of the National September 11 Memorial and Museum in New York City, said international museum planning firm Gallagher and Associates has signed onto the project. The company designed the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

The Medal of Honor Museum would include artifacts, as well as multimedia exhibitions. Daniels wants to go beyond “flat panel text” and take visitors into “an immersive environment where when you leave, you know the stories behind the names of those that have earned the medal.”

After the foundation announces the selected city around Oct. 2, it will launch a national design competition. The foundation anticipates about four to four and half years to build the museum.

A statement from Gov. Jared Polis’ office said, "We are thrilled and honored that Denver is a finalist for the National Medal of Honor Museum. It presents an historic opportunity to showcase all of the unique military and veterans assets in Colorado. If we do win this project, any consideration of state resources would follow standard State procedures.”

President and CEO of the Downtown Denver Partnership, Tami Door, said few cities still have space in their “core civic area where another piece of the puzzle can be placed.”

“We have that piece and what is really important to us as a community is that we fill that piece with the right project,” she said. “The fact that these two things have convened at the same time, that we still have that land on our premier civic space and that this couldn't be a more premier project, we feel very fortunate to be in these discussions.”

A False Start In South Carolina

The museum was initially planned for a site in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, a suburb in Charleston County. After six years of talks and negotiations, the plan collapsed and the foundation started to look elsewhere.

Daniels said the foundation had a change of heart when it began to look at the Mount Pleasant tourist market, questioning if it was big enough to sustain such a project. The foundation wants the museum to measure “visitation in millions and not in thousands and that's why we embarked on this national search,” Daniels said.

The Charleston area saw about 6.9 million visitors in 2017, while the Denver metro drew 31.7 million. Daniels said they expect 750,000 to a million visitors every year, depending on the size of the museum building.

A lengthy report from the Charleston Post and Courier recounted the communication breakdowns between the foundation and the town. The local newspaper reviewed thousands of emails and correspondence between the museum and town leaders, as well as people involved with the original proposed site, and found that “acrimony and suspicion had infested the much-vaunted project for many months. Each party involved, in some way, had felt bullied, misled or both.”

There was also confusion over the design plans, as the foundation’s proposed design, in particular the height of the museum, wasn’t in accordance with zoning ordinances.

Daniels said the failed attempt in South Carolina taught the foundation that “you don’t build on public land without public input.” The CEO added that, this time around, they’ll be “very transparent about the process of how decisions get made.”

“We want to feel that the city of Denver, on the day that we open, is this proud as anybody who is connected to the museum,” he said. “This should be a project of Denver, not being imposed on to Denver.”

Back in South Carolina, a new effort has formed to launch the area’s own Medal of Honor tribute. Led by Medal of Honor recipient and retired Marine Maj. Gen. James Livingston, who was once with the foundation but left in 2017, the National Medal of Honor Heritage Center would cost around $35 million. The county council recently voted in favor of some taxpayer money for the project, according to The Post and Courier.

Of the effort, Daniels said he supports it, pointing to several other similar institutions, such as the Charles H. Coolidge Medal of Honor Heritage Center in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He’s not concerned about any kind of saturation or confusion in the marketplace.

“From our perspective, as many projects that exist around the country really just help raise the profile of the medal,” he said.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that RTD's board voted on the proposal from the foundation.