The students use prison-issued inch-long pencils. They sit down to write, like they always do, but now it’s about how people around the country are dying behind bars. They try to imagine what the world outside thinks of them.

As the world exhales,

diseased exhaustion overwhelms us.

We wheeze in contaminated air as we lumber past,

struggling, coughing, and glaring through disgusting judgmental eyes.

This is our hot zone, right here, right now.

But who cares when the disposable die?

Pain has been passed forward, and the truly moral

know we deserve a cold sweat-laced

suffocating death, alone, chained to a

hospital bed.

"No intensive care for this one doc

He's below us doc.

Below the winter grass doc.

Below the clay lining Victorian cesspools doc.

No… Let 'em go doc.

Let 'em go."

Viral clouds linger among our

crowded bunks.

Fugitives no more,

we breathe in and hope to meet God

-Todd Deal, Lansing Correctional Facility, Lansing, Kansas

When you live in a cell, your cellmate is within sneezing distance. Coughs ricochet off the cement walls. Everyone is vulnerable to coronavirus infection, and in prisons it’s especially true, since in addition to close quarters, high numbers of inmates have underlying medical conditions.

That vulnerability has quickly turned into infection: In Colorado, more than 200 inmates have tested positive at the Sterling Correctional Facility. Last week, a state inmate who had symptoms of COVID-19 died. Across the country, as of April 29, at least 14,513 people in prison had tested positive, a more than 50 percent increase from the week before, according to the Marshall Project.

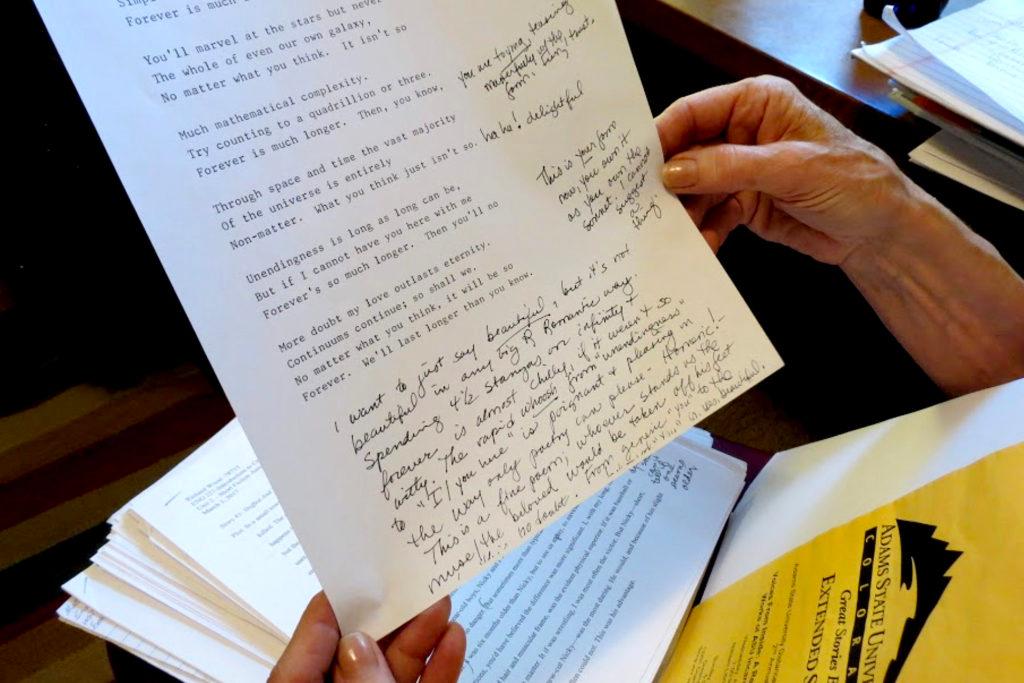

Some prisoners, faced with the pandemic but powerless to do anything about it, are writing about their own experiences, and interviewing the people around them, as part of Adams State University’s Prison College Program.

“I’m really afraid I could die any day,” one California inmate tells a fellow inmate as part of an assignment for an Adams State course, adding that “the fear among inmates is not widely known, but it’s real and palpable.”

The writings in this story were provided by Adams State University and the program’s instructors, Carol Guerrero-Murphy and Kathy Park Woolbert, who live in Colorado. The prisoners live around the country, and unless otherwise noted, we are not using their names to protect their privacy.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, across the country, prison education programs have largely shut down.

That’s because many are onsite. But Guerrero-Murphy of Superior, Colorado, continues to teach writing to students enrolled in the Adams State program. She does so via correspondence. Some prisons have onsite higher education programs affiliated with them, but for prisons that don't, Adams State is one of the only prison education programs nationwide that offers classes through the mail.

Starting in early March, Guerrero-Murphy and Park Woolbert of Alamosa began seeing bits and pieces of writing about the coronavirus from their incarcerated students who are on lockdown because of the pandemic. An incarcerated student in Tennessee writes:

I fear Covid-19 is sweeping this prison. I live in very close proximity to seven other guys and the whole pod is open. The prison system has suspended visitation state-wide, but we're still at the mercy of free-world staff working here. Staff and inmates don't generally come in that close of contact, but that is small comfort for a virus that can spread by mere talking, even by asymptomatic people.

Guerrero-Murphy says amidst all that uncertainty, “These students' descriptions of the increased confinement, confusion, and pressure around them, written while they struggle to meet the requirements of an academic course within a crumbling prison education infrastructure, reveal how being part of a prison education program really is a light in an often dark world for them.” She continues, “just as their motivation and dedication to their coursework is a light to me in an often dark world. As ever, I learn from my students.”

The courses Guerrero-Murphy and Park Woolbert teach have included fiction writing, foundations in literature, poetry, argumentative research, creative writing and the prison memoir. The instructors believe writing allows self-reflection, healing and ultimately, a way to start to come to terms with the crimes they’ve committed. One major study showed that prisoners who take part in educational programs are 43 percent less likely to reoffend, and those who participated in vocational programs had a 28 percent higher chance of getting a job than those that didn’t.

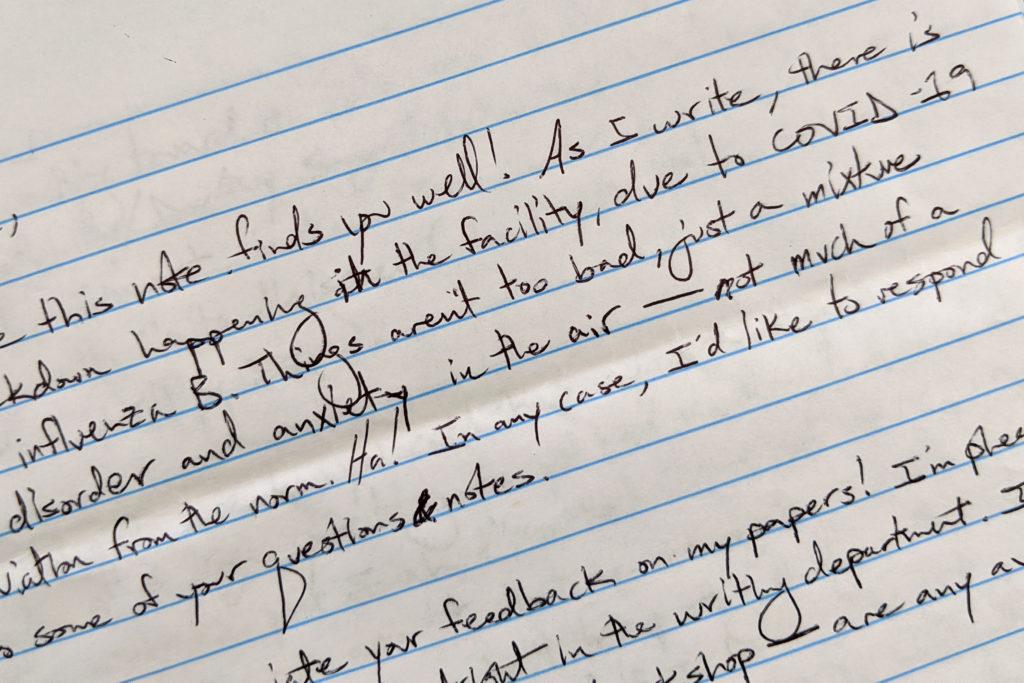

Sometimes students write brief greetings to the teachers on their cover letters, a small window of what life feels like in prison during the pandemic. From an incarcerated student in Michigan:

“I hope you are staying healthy during this chaos. I believe in a lifetime we only experience two or three historic happenings and I believe this is one. My facility has the virus spreading like crazy. When a guy tests positive they put all the guys near him into a makeshift quarantine housing unit for at least 14 days. A guy near me tested positive so I was moved to quarantine. We are crammed into a small space with no tables or desks. I wrote this while lying in bed. And the noise! It is so difficult to concentrate. I'm not making excuses but I feel this is not up to the writing I want.”

In their writings, inmates show a self-awareness about what people on the outside might think of them. An inmate in California, in a two-page essay on whether overcrowding in prisons in a time like this is a violation of the constitution’s Eighth Amendment, wrote that some argue that sickness and death are among the risks an inmate assumes when they are sentenced to prison.

“.... there are those who are not particularly empathetic to prisoners because of society’s belief that they are to expect risks like this when they went to prison. A fellow inmate of mine [name] said matter-of-factly, “we face death every day from all the guys around us. Those guys who have life sentences are as good as dead already. Dying of the virus may be a quicker way to end this misery.”

He’s not alone. Others write of their increasing isolation when prisons went on lockdown, where they have no access to phones or email.

“Right now I feel like I'm seeing everything crash and go under… I'm seeing the impact that this virus is having on the global, national, and local economy at a time when I'm nearing my release from prison and will have to reenter the workforce.”

This incarcerated student in Florence, Colorado, worries about his girlfriend back home, a hospital administrator who has been “shaken to the core” after recent earthquakes during the pandemic. He writes of his lack of ability to support her and worries about his father.

“My father is 64 years old with a heart complication. He is a physician's assistant and works full-time in an emergency room and part-time in an urgent care clinic. He's told me that he is wearing protective gear and taking precautions and he tells me not to worry. Not worrying when I'm locked up in a box hundreds of miles away when all of my loved ones are at risk isn't easy."

The inmate writes that it is frightening to watch the world go through such drastic changes that he thought were never possible in his lifetime. But still, he writes, “Despite all of the changes that are happening right now the important things will stay the same: seasons will come and go and life will go on.”

How do you write final exams in prison during a pandemic?

“Some of the students write wonderful things,” Guerrero-Murphy says. “Such as ‘There is a general feeling of anxiety and chaos, not that different from the usual,’ which is darkly humorous. Others are naturally worried about being able to finish a course or degree program.”

Final exams for prisoners in education programs are coming up. Typically, they are proctored by an outside person. An incarcerated student in Nevada was negotiating how to get his final exam proctored, but a top official at the prison just tested positive for COVID-19 so his prison is on complete lockdown. He called the situation “grim.”

“I would be eternally grateful for an alternate assignment in place of my final exam,” he writes to a professor. “Please take care of yourself. I'm worried about you and your well-being. These are mad times we live in, mad times I tell you (a line from Harry Potter.) At least you have your work to stimulate your mind. ... Anyways, please stay safe professor.”

But Adams State has created alternatives to exams because of the prison lockdowns.

“We want to do all that we can throughout this crisis to help our students achieve their higher educational goals,” said Matthew Martinez, director of the Correspondence Education Program at Adams State University, who has encouraged instructors to be flexible with the students throughout this outbreak.

If proctors aren’t allowed to enter facilities, a Department of Corrections staff member can proctor. If that’s not possible, instructors can provide an alternative assignment to substitute for exams. “If an instructor is unable to provide an alternative assignment, we will grant an extension until the lockdown lifts,” Martinez said.

Over the coming months, prisoners will continue to be at extreme risk of infection with few ways to protect themselves. But the inmates in Adams State University’s prison education program will continue to painstakingly shape and reshape their writing, each new draft necessitating one new stamp.

The California inmate writing about whether overcrowding during a pandemic violates the Eighth Amendment also writes that keeping prisoners locked up in close quarters has cost lives, and continues:

“No prisoner should have to pay that price morally or legally.... No matter what people may think of prisoners, let’s not forget that they are human beings. Most will reenter society someday and be neighbors and coworkers.”

Editor's note: This story has been corrected to clarify that the writings in this story were provided by Adams State University and the program's instructors in compliance with privacy laws. The author of the first poem authorized the use of his name.