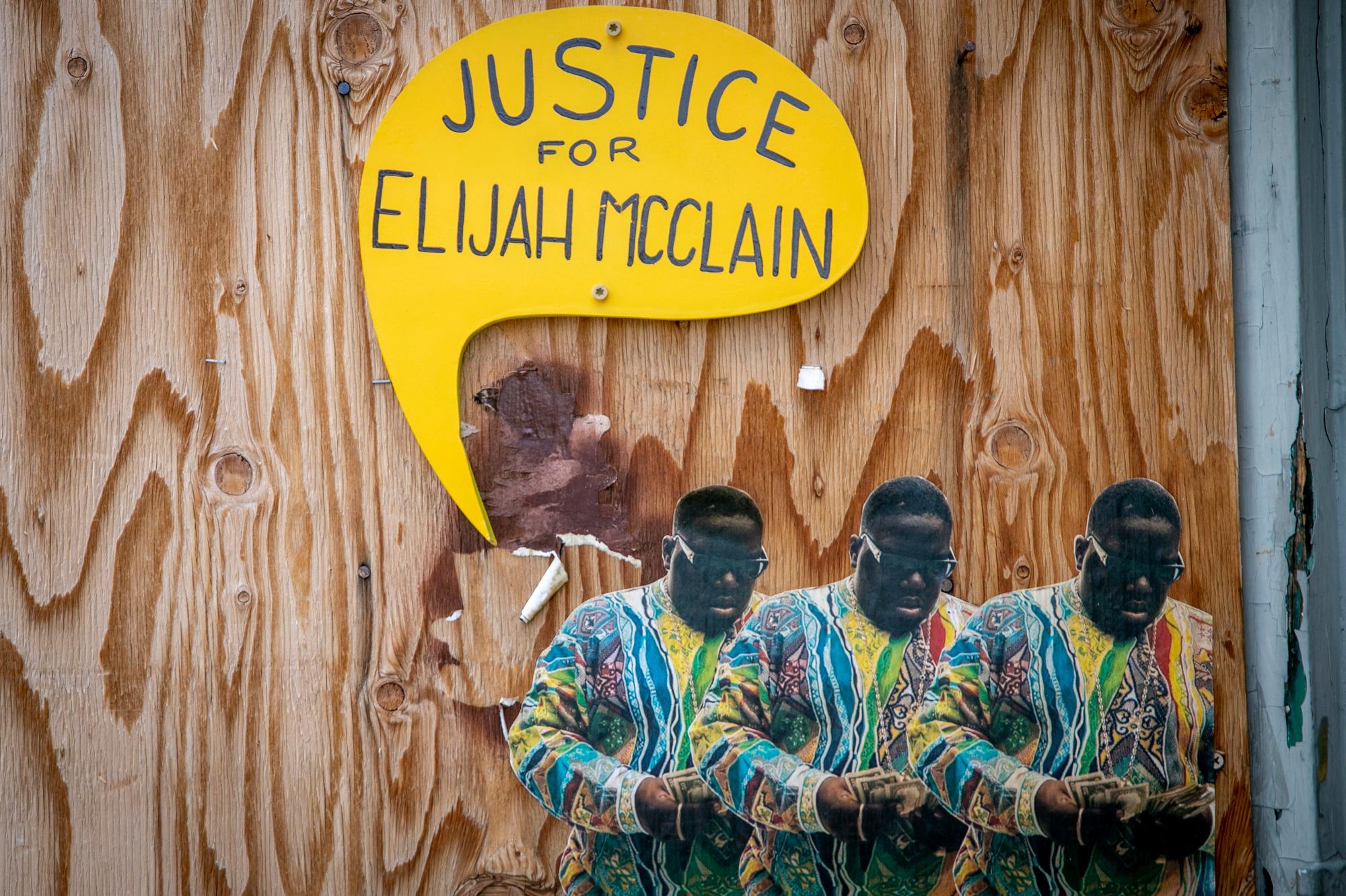

In late June, as Aurora officials held a virtual discussion about the way police had handled protests of Elijah McClain’s death, the federal government made an uncharacteristically candid disclosure.

A trio of agencies said they had been investigating McClain’s death since 2019.

Federal officials have declined to elaborate on the details, noting the standard practice is that they don’t announce the existence of ongoing investigations.

“However there are specific cases in which doing so is warranted if such information is in the best interest of the public and public safety,” according to a joint statement issued by the Colorado U.S. Attorney, the Denver Federal Bureau of Investigation and the U.S. Department of Justice.

But a case in Adams County that fell under the same prosecutor who initially probed McClain’s death might reveal how the federal government will bring charges against the officers involved in his arrest.

The Curtis Lee Arganbright case in Westminster

In 2017, Westminster police officer Curtis Lee Arganbright was giving a woman a ride home from the hospital when he pulled over, handcuffed her and sexually assaulted her. Arganbright was convicted of unlawful sexual contact and official misconduct in state court and sentenced to 90 days in county jail.

That wasn't the end of his story.

The federal government launched its own investigation into what had happened using a law applied to cases in which officers have potentially deprived people of their civil rights.

Investigations under United States Code 242 are extremely rare: In 2019, federal prosecutors brought charges in just 49 such cases across the country out of more than 184,000 total prosecutions, according to research from Syracuse University.

Last year, Arganbright pleaded guilty to one count of a Code 242 violation and now faces up to 10 years in federal prison. His sentencing, which has been delayed because of the pandemic, is scheduled for October, and he is out on bond.

After Arganbright’s plea, Colorado’s U.S. Attorney Dunn said that when federal prosecutors “see an injustice, we will not hesitate to step in, particularly when it involves vulnerable people or those in positions of power.”

If charges are filed against the officers involved in McClain’s death, a jury of Coloradans would have to be convinced that the officers had in fact broken the law — on purpose.

But from the Rodney King beating to the shooting of Philando Castile in Minnesota in 2017, juries have proven reluctant to hold officers accountable.

What happened the night of Elijah McClain's death

McClain died in August 2019 after three Aurora police officers stopped and attempted to detain him, placing him in two carotid chokeholds. McClain fainted and vomited, and when paramedics arrived, they injected him with ketamine.

In an ambulance en route to a hospital, medics noticed his chest wasn’t rising on its own. McClain had gone into cardiac arrest. He was disconnected from life support several days later, according to investigative documents and the Adams County District Attorney.

Officers had stopped McClain, who was walking down the street, after receiving a 911 call from a man nearby who said he looked “sketchy.” The caller said, “he might be a good person or a bad person.”

McClain, who had a blood circulation disorder, was wearing warm clothes and a ski mask on that late summer day. He was not suspected of committing a crime when cops asked him to stop. Police have the right to briefly detain a person based on “reasonable suspicion” that he or she was involved in criminal activity.

Body camera footage shows an officer getting out of his car, pointing at McClain, and telling him, “Stop, stop, stop, stop, I have the right to stop you because you’re being suspicious.”

Officers then quickly grabbed McClain and turned him around, telling him to “stop tensing up.” They then took him to the ground, calling for backup because they said McClain was “fighting” them. McClain was heard on body camera footage telling officers, “please respect my boundaries.”

- Hundreds ‘Keep Fighting For What’s Right’ At Car Protest For Elijah McClain

- ‘This Is Enough’: What 83,000 Emails Ask Of The Colorado Lawmaker Who Represented Elijah McClain

- Aurora Fires Three Officers Involved In Photo Mocking McClain Death

- Thousands Call For Justice For Elijah McClain In A Day Of Music And Marching

University of Denver Sturm College of Law Associate Professor Ian Farrell, who has studied bodycam footage of the incident, said he did not believe the arrest was reasonable under the law.

“They (the cops) immediately grab him, now they’re using physical force and once again, the question of whether that physical force is excessive force is one of reasonableness, the test is whether that’s reasonable,” Farrell said. “My view is at that moment, it is not reasonable. He has not resisted in any way.”

Mari Newman, the McClain family's attorney, is preparing to file a civil rights lawsuit against the Aurora Police Department for his death.

“The violation of his civil rights began at the very moment they stopped him,” Newman said. “The 911 caller made it clear that Elijah was not suspected of committing a crime, no one was in danger, and Elijah was not armed. Yet Aurora police physically seized him, tackled him, tortured him, and ultimately killed him – all without ever even having reasonable suspicion to believe he had done a single thing wrong.”

Why federal prosecutions into local police are so uncommon and hard to pursue

Federal prosecutions of law enforcement actions are rare because the bar is so high for a grand jury indictment of a police officer under Section 242. Prosecutors must prove an officer “willfully” violated someone’s civil rights.

“Mistake, fear, misperception or even poor judgment does not constitute willful conduct prosecutable under the statute,” the Department of Justice has said. “It requires that the government prove that the law enforcement officer intended to engage in unlawful conduct and that he/she did so knowing that it was wrong.”

Rachel Harmon, professor of law and director of the Center for Criminal Justice at the University of Virginia, used to work on Code 242 violations at the U.S. Department of Justice. She said the cases are complicated and “very difficult to prove.”

Harmon said that if she was investigating McClain’s case for the federal government, she would focus on whether the stop and arrest was legal and whether police used excessive force.

“Were his rights deprived? Did the officer willfully deprive him of his rights, did they intentionally use too much force?” Harmon said, noting that, generally, courts have determined that chokeholds are considered “deadly” force. “If an officer at the scene is using deadly force on a suspect clearly not dangerous, non-violent, that’s easier to establish willfulness.”

Last year, Adams County District Attorney Dave Young cleared the officers involved in the McClain case — Nathan Woodyard, Jason Rosenblatt and Randy Roedema — of any criminal wrongdoing.

Young’s office also initially oversaw Arganbright’s case. Through a spokeswoman, Young declined to comment on either case on Thursday.

The three officers told investigators that McClain was attempting to go for Rosenblatt’s gun, which was holstered. In body camera footage, Roedema can be heard saying “he is going for your gun,” according to Young's decision letter not to charge the cops.

But there are no visuals: The officers said their body cameras had dislodged from their uniforms, according to the district attorney’s clearance letter. The officers then took McClain, who was 140 pounds, to the ground.

“Conveniently, all three officers shed their body cameras as soon as they went hands-on with Elijah, ensuring that there would be no video to show what actually happened,” Newman said. “But as happens when people are making things up, they couldn’t keep their stories straight. Roedema claimed Elijah was trying to grab Rosenblatt’s gun; Woodyard later claimed Elijah had tried to grab his gun. Rosenblatt admitted he never felt anything. But one thing rings true: a peaceful young man who does not even kill flies would not have tried to grab anyone’s gun.”

Harmon said federal investigations usually take place after the state’s investigation is concluded.

But the McClain case is an outlier because there are three separate investigations occurring at once: one each from the city of Aurora, the state attorney general, and the federal government.