Sixth-grade science teacher Garrett Peirce has chronic myeloid leukemia, a type of bone marrow cancer. Still, he says he’s not afraid to go back to the classroom in two weeks, when Grand Junction schools get started. But when he saw the reopening plan unveiled at a school board meeting in Grand Junction, he was disappointed.

The details he needs to feel safe just weren’t there.

“Who’s going to clean the classrooms after one period leaves in the next period's coming in? Is that going to be me? Where's that material coming from?” he asked the board.

“If we only have 50 percent of the kids in the cafeteria, who's watching them? Are (some) eating in my classroom? Who's cleaning up my classroom after that?”

He pointed out that even at the board meeting, some people weren’t properly masked.

“So if you guys aren't policing it, how am I supposed to police it in class?”

Mesa Valley School District did survey teachers about safety measures and questions they have about COVID-19’s impact on the district.

CPR reviewed teacher surveys from 25 districts and found big variations in how much districts tapped into what teachers thought. Still, Kevin LaDuke, a 30-year veteran in Grand Junction, summarized what many teachers across the state are feeling: “We were the last ones to take any survey, and we were the last ones to put our voice in. And that is wrong. We should be the first voice. We are the first in line.”

The surveys revealed that educators’ anxiety isn’t just about staying healthy, it’s about new and complex academic plans that could make teaching challenging and widen achievement gaps.

Were teachers consulted?

School districts say they’ve been working around the clock, updating plans on a weekly basis, hosting virtual question and answer sessions, fielding thousands of questions from the public, and have consulted with teachers as much as possible. Still, a review of the surveys reveals teachers were sometimes excluded from the development of reopening plans, or consulted infrequently.

Some school districts, like Poudre, released hundreds of pages of teacher comments and questions to CPR, information that gave districts valuable insight into what’s on educators’ minds. It’s unclear how much of that insight ended up into district plans. The district announced Tuesday that it’s starting with all remote learning.

Other districts didn’t survey their teachers — like Mapleton, 27J in Brighton, or St. Vrain Valley Schools — but may have included them in staff-only virtual town halls, on reopening committees or through online feedback forms. Some districts, like Greeley, conducted their only survey of teachers in May, when the majority of teachers didn’t want to return to fully online classes. A lot has changed since then.

Teachers in Durango say they weren’t consulted until July 30, after the restart plan came out, despite asking to give input multiple times.

“I think that either a (Colorado Department of Education) official should have had a pulse with different teachers around the state, as well as the local districts should have been keeping the teachers, educators, the chefs, the janitors, everybody that's going to be involved, should there should have been a voice at the table for all of this,” said Amanda McKown, a teacher in Durango.

A Durango spokesperson said teachers “were involved in the work with their instructional leadership teams, through their school leadership, and through their associations.”

McKown, who helped conduct a union survey of teachers, says teachers have concerns about students self-screening at home, a lack of air conditioning and windows in buildings, a “rushed” timeline to get lessons prepared, and how sick leave will work. The district’s draft plan offers families all three options: in-person, a hybrid model, a mix of remote and in-person, and fully remote learning. McKown says teachers don’t know yet what or how they’ll be teaching.

“Nothing has been detailed yet,” she said. Public feedback sessions are scheduled this week. Durango teachers return to work Aug. 17.

- How Will Denver Public Schools Handle Equity In Online School, And Four Other Back-To-School Questions

- High School Football And Other Sports Cement Spring 2021 Seasons As Colorado Coronavirus Cases Fall

- What Teachers And Parents Are Saying Ahead Of Colorado Schools Reopening

- What Is Cohorting? And Is It The Cure For Colorado’s Coronavirus School Worries?

- Colorado Gears Up For Online Learning With Digital Access Push — And One Victory for Undocumented Families

Other districts and school boards have tried to work more closely together.

“The education association has been a great partner so far and I really appreciate their work and I think I’m not the only one on the board who feels this,” Littleton school board member Robert Reichardt said during a board meeting when the district unveiled its recommended plan.

Amanda Crosby, president of the Littleton Education Association, said teachers sat on the LPS Restart Task Force, wrote letters to the editor and to district officials.

“I think the messages from educators are breaking through with district officials and with the school board,” she said.

Many Littleton teachers are still uncomfortable and have many questions. But the union has shared its own survey with the district, revealing valuable information to help guide school leaders. For example, teachers overwhelmingly believe that a health screening system that relies on parents and older children taking temperatures before school would be less effective than the school doing screenings on site. It revealed that teachers are evenly divided on whether they thought students could wear masks all day. And like many other teacher surveys, it revealed an uneasiness about returning to in-person learning.

“There are some people who are ready to return and comfortable, there are some that just don’t feel they can be made to be comfortable,” Crosby said. “And there are some who feel that more actions by the district and the association and their school building ... could make decisions that might make them feel comfortable.”

Aurora Public Schools met with teachers in the spring. Since then, the district has provided updates to union leader Bruce Wilcox. He, in turn, has had hours of meetings with grade-level staff and specialized staff like speech pathologists.

Wilcox said teachers have insight to tap. An early version of the restart plan would have required schools to turn away kids without masks at the school door. He said many kids in his district get up and get themselves to school because parents are already working.

“If you had asked us (teachers), we would've said this is essential, that we have some kind of support mechanism for these students when they get to school without their mask,” he said.

Some of the disconnect between districts’ plans and teachers may be due to the speed with which everything is happening. Wilcox said the plans may in fact address teachers’ concerns, but those details haven’t been shared yet. He said in Aurora, teachers were relieved when that district decided to go remote for the first quarter, to give them time to get their heads around everything.

“The more teachers we could have gotten involved, we may have been able to answer — and still may be able to answer some questions before we go back to full in-person learning,” he said.

Do teachers know what they’ll be doing this fall?

While school district staff have spent weeks putting together return-to-school plans, teachers say they haven’t had the same time to help figure out how things will play out in classrooms.

That’s widespread. A national analysis of state reopening plans said state guidance on reopenings mainly focused on health and safety practices, but lacked detail on how to engage and keep students on track in remote learning. It concluded, “the absence of clear expectations is certain to contribute to inequities across school and district responses.”

The Roaring Fork District, which includes Glenwood Springs, Carbondale and Basalt, is expected to open schools with an “enhanced” remote learning model for all students starting Aug. 17 and staying remote until at least Sept. 21.

Teachers praised board and district efforts to come up with a plan but say too many unknowns remain. Maureen Hinkle, a music teacher at Basalt Elementary told the school board on July 29 she has a lot of “nitty-gritty” questions about what school looks like day-to-day.

“As the music teacher am I going to be teaching music to the whole school or am I going to be assigned my own cohort? I need to know these questions now,” she said.

Another teacher noted that participation among her students who are learning English during remote learning in the spring was less than 40 percent.

“I just don’t want to see them get left behind so we really need to figure out how they will learn best,” said middle school teacher Krista Lasko.“My fear is that if we continue with digital learning for a long time, the gap (between them and more affluent students) is just going to get bigger. They won’t get the education they deserve.”

She said she’s willing to teach wherever she is needed but also wonders if Spanish classes are off the table for now.

“The answers will come as we all figure them out,” said board president Jen Rupert. It’s a common refrain as district leaders navigate rapid changes in the course of the pandemic and the community’s needs.

Practical health and family concerns also shape teachers’ sense of preparedness. Some districts’ surveys reveal large numbers of teachers who could be vulnerable themselves or have vulnerable family members if there are COVID-19 outbreaks. When asked if they or someone they care for puts them at a higher risk of complications from COVID-19, almost half of teachers in Aurora’s district did. Meanwhile, in Mesa County Valley Schools, the vast majority of school staff had no concerns. Teachers with chronic health conditions will have higher priority for remote assignments in many districts.

Teachers’ childcare obligations at home will also need to be accounted for. A third of DPS employees indicated they’d need help with child care for their own children if they were teaching remotely. But this too varies district to district: Only 14 percent of Douglas County teachers said they would need child care help in a fully remote model.

One teacher told CPR the district where she teaches will require her to go back to face-to-face learning with up to 30 children per classroom. Her own children go to a different district with a hybrid start with two days in school, and three days at home.

“As a single parent there is absolutely no way I can make this work without quitting my job or subjecting them to daycare/after school care,” she said.

Surveys show deep concerns about districts’ abilities to pull off remote and hybrid learning.

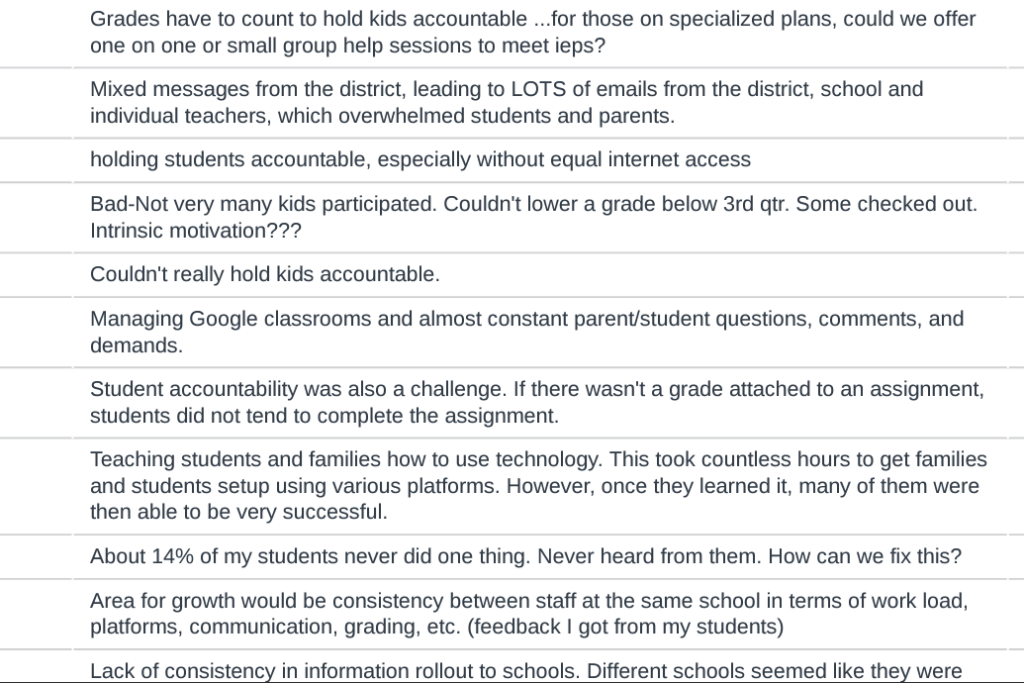

During spring remote learning, 42 percent of Poudre teachers said they had challenges using technology that affected their ability to complete their job. In pages of survey data, teachers told the district the things that worked well during remote learning: “using online tools (Flipgrid, Padlet, Gamemaker) to engage kids, daily check-ins with colleagues, weekly menus to give students choice, team meetings, and reaching out to students individually about their thoughts.”

But major problems loom, if there isn’t a massive investment in technology and training.

“When both my husband and I were running online video sessions, one or the other of us would get bumped off and that is really stressful when you teach kindergarten because it makes them cry when the teacher disappears and can't get back in,” one wrote.

The Poudre district solicited hundreds of answers from educators when asked what they’d need to continue remote learning in the fall. Teachers responded with an extensive list of needs: standardized technology, time for classroom aides to work with teachers prior to lessons, more planning time, better connectivity for some students, the ability to grade students, technology training, training on getting parents and children consistently engaged, childcare for teacher’s children, clear and direct guidelines.

One teacher wrote simply: “Just a hug from time to time.”

Steve Villareal, president of the St. Vrain Valley Teachers Association, said part of the challenge is just the uncertainty and lack of stable plans.

“Being a teacher myself, we're planners, we want to know the uncertainties,” Villareal said. “We want to be ready. We want to be prepared.”

He said districts should give teachers more time to prepare before students get back to school, and time to plan as the school year goes on and unexpected issues arrive.

Perhaps the teachers rattled the most are teachers doing hybrid learning — a mix of remote and in person teaching. One in Jefferson County told CPR she expects to have her workloads doubled. At the moment, she’s juggling hybrid learning and teaching for students who’ll learn entirely remotely. That means preparing lessons for half her class attending in-person, taped lessons for the other half at home, and lessons for students who’ve chosen all remote. The school district said it’s still determining how many families prefer which model and whether the numbers will allow schools to dedicate some teachers solely to remote learning and take that off other teachers’ plates.

- Cherry Creek Schools To Open For In-Person Classes — But Not All Students Will Return To 100 Percent In-Person

- Mesa County Public Schools Will Let Parents Choose Between In-Person Or Remote Learning When Classes Begin In August

- Denver Public Schools Will Extend Remote Learning Through Mid-October

- Douglas County Schools Plan On Hybrid Schedule To Reopen Amid Rising Cases of Coronavirus

- With COVID-19 ‘Virus Levels’ Driving Decisions, Jeffco Schools Will Start The Year Remotely For Its First Two Weeks

Virtually all teachers say in-person learning is the best way to teach the vast majority of kids.

But in a global pandemic, some teachers are more ready to go back to in-person learning than others.

In southern Colorado, plans for how to safely reopen split look very different on either side of district lines. Pueblo School District 60, which includes the city of Pueblo, surveyed its school staff in a single question survey in late June. The vast majority of staff-preferred reopening school with some form of in-person learning — either half time or fully in-person. The current plan for Pueblo School District 60 — formerly Pueblo City Schools — includes in-person learning for elementary school students, with middle and high school students in a hybrid model or fully online starting Aug. 31.

Outside the city, however, Pueblo County School District 70 will start remotely for all students for four weeks. After seeing a large increase in COVID-19 infections in the county, 43 percent of teachers said they wouldn’t feel comfortable returning to school until January or after a vaccine is found.

“The fear, the concern, is very palpable,” said Amy Spock, president of the Pueblo County Education Association, adding that chronic underfunding has left some class sizes at 35 to 40 children. “Are we going to be compromising our community? Schools were built for socializing. They weren't built for social distancing.”

Pueblo 70 also specifies that students won’t be let back into schools full time until transmission rates drop below 2 percent.

Spock said teachers worked closely with the district, giving feedback and developing plans for fall. The District 70 local teacher’s union conducted two surveys, quizzing educators and classified staff on everything from if they want Plexiglas shields to teaching students remotely and in-person at the same time.

Similar patterns emerged in metro Denver. In June, nearly 65 percent of Douglas County teachers believed students should return to school in the fall, and in a hybrid model. More than half said elementary kids should be in school five days a week. Only 10 percent agreed with 100 percent remote. Meanwhile, a few miles away in Jefferson County, only 5 percent of teachers in a local teacher’s union survey of 3,000 licensed staff would feel "moderately" safe returning to in-person learning unless the district brought in more safety measures than it’s already planned for.

JeffCo teachers recently held rallies demanding that schools go remote into October. The district’s current plan calls for schools to start remotely Aug. 24, with elementary students beginning in-person learning on Sept. 8 and older grades alternating in-person and remote learning.

Some questions highlight how impossible it will be to please all teachers, especially when COVID-19 conditions and guidance changes weekly.

In Adams 12 Five Star district, north of Denver, staff were asked what the district's guidelines should be for mask-wearing. About half said all the time. But 40 percent said only in the general public, and 11 percent said it should be the staff’s choice.

In spite of the local differences in opinion, teachers and school districts alike agree that much of the chaos stems from factors beyond their control, from mixed messages from politicians, a lack of leadership at the state and national levels leaving districts responsible for figuring this out, and scientific information that has been contradictory and at times politicized.

“That is really, in my opinion, just created this angst and this churning among teachers,” said teacher Villeareal, the St. Vrain union leader. “Who's leading this, who's the guy in charge that is going to make sure that this is going to work?”

On top of that, he says the school system lacks the resources needed to respond. Budget cuts due to the pandemic-related economic downturn, on top of decades of dwindling finances, have left school districts with few margins to respond to a crisis of this scale.

“It’s the perfect storm, unfortunately,” he said.

The bottom line may simply be that individual schools haven’t had the time to work out how plans will be executed at the classroom level. That’s amped up the anxiety for teachers — and parents. Others say however children return to school, it won’t be like it was and everyone — parents, teachers, principals and students — will have to demonstrate an extraordinary amount of patience and flexibility to make it work.