Going into this year’s election, state Senator Kevin Priola of Henderson was a top target for Democrats. Priola is the legislature’s most moderate Republican, and with his district shifting increasingly blue, he was also looking like possibly its most vulnerable Republican incumbent.

But Democrats, who otherwise had a good election cycle in Colorado, didn’t succeed in taking Priola’s seat. And his political survival could highlight one path forward for Republicans in a state that has in recent years elected Democrats to its highest offices.

Priola likes to joke that his district, which covers much of Adams county northeast of Denver, has it all... other than a beach and a mountain.

“There are dryland wheat farms in my Senate district. There are urban neighborhoods, suburban, bedroom communities, commuter communities,” he said.

That diversity includes a lot of voters who favor Democrats. In 2018, when Priola wasn’t up for election, the district narrowly voted blue for statewide Democratic candidates, including Gov. Jared Polis. While precinct level results aren’t yet available for the recent fall election, president-elect Joe Biden won Adams County overall by nearly 13 points. Democrat John Hickenlooper received about the same margin in his U.S. Senate race against Republican Cory Gardner.

Priola’s race was much closer. Preliminary results show him defeating his Democratic opponent, kindergarten teacher Paula Dickerson, by just over 1200 votes.

“I've been impressed with Priola and I'll be honest, I didn't vote for him four years ago,” said Blaine Nickeson, one of the split-ticket voters necessary for Priola’s victory.

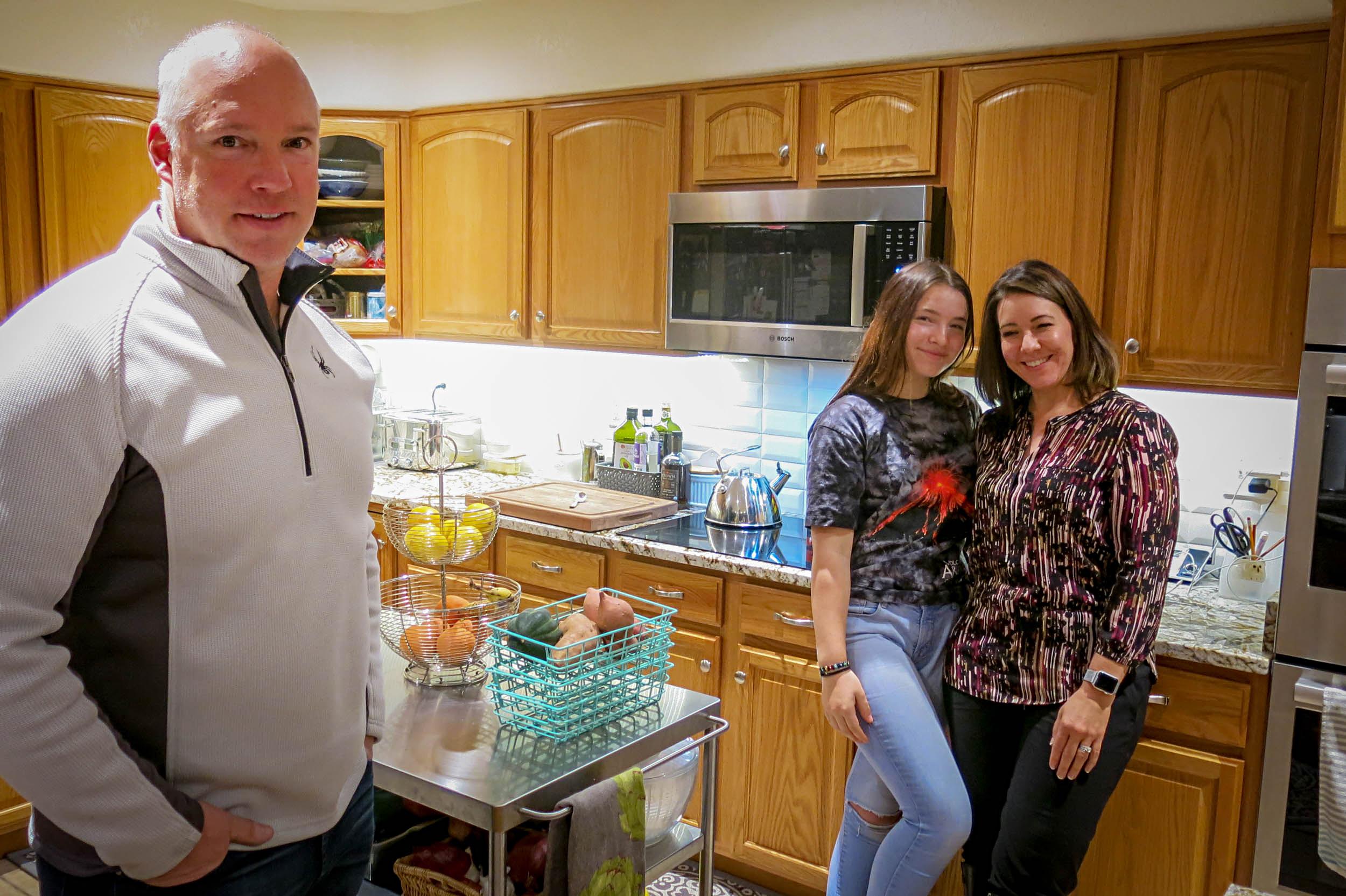

Nickeson and his wife are Democrats and live with their young children in Brighton. He serves on the local school board and also manages the University of Northern Colorado’s response to COVID-19. He considers himself a policy wonk and says when it comes to education, human rights and racial justice, he’s liberal. Priola is the first Republican he’s voted for in 16 years.

“I felt like it was important to sort of practice what I preach, you know,” he said. “If we're really going to value bipartisanship and people who are willing to work with other folks, we need to back that up with supporting people who are sort of walking down that middle line.”

It helps that Priola has a long history in his district. He was born and raised in Adams County and has served in the state capitol for a dozen years, first as a Representative before term limits led him to move over to the Senate four years ago. He married his high school sweetheart and they are raising four children.

Around the capitol, Priola is known for bucking the GOP on controversial issues, which often brings him a lot of grief from the more right-leaning members of his party.

In recent years Priola has supported a safe injection site in Denver for drug users and signed on to a ballot proposal to let Colorado keep extra tax money for education and transportation. Both of those ideas did not come to fruition. He’s also worked with Democrats on measures aimed at preventing opioid abuse, and simplifying health care billing.

But while Democrats often relish the bipartisan clout his name provides when he agrees to co-sponsor one of their bills, that didn’t protect him this election cycle. Even if Democrats like working with him, he was still at the top of their list to defeat.

Ian Silverii heads ProgressNow Colorado and used to work with Priola on education policy issues when Silverii served as chief of staff to the Democratic House majority. Silverii gives Priola credit for successfully making the case that his bipartisan record is still a good fit for the district.

“If you were a candidate that was able to fend off what is obviously a big blue wave in Colorado: congratulations,” Silverii said. “But it is very clear that the state is moving in a very progressive direction.”

Priola says he went into things knowing this would be his toughest campaign yet. He started going door-to-door in May to talk with voters. It was a lonely effort, since he said help was hard to come by due to the pandemic. On his own, he knocked on doors five to six days a week, usually from 1pm to 7 in the evening.

“It’s just about building relationships and finding common ground and understanding, listening to them,” said Priola, of his approach to connecting with constituents. “I asked them what's on their mind. I don't roll up and tell them how right I am, [how] smart I am, on all these issues.”

Priola’s one-man ground game even had an effect on other races on the ballot. Democratic county commissioner Eva Henry said she stepped up her own re-election efforts in the part of Adams county Priola represents. She was concerned his campaign might help boost her Republican opponent.

“Kevin is a really good campaigner. He works hard and he works hard for his district, is the reason why I think he won. And he's very relatable. People can relate to Kevin.”

That same mix of personal appeal and more moderate policy positions also helped another Republican state senator narrowly hang on: Bob Rankin of Carbondale, who won by 990 votes.

Rankin’s sprawling mountain district covers much of northwest Colorado. More liberal voters in towns like Silverthorne, Steamboat Springs, and Glenwood Springs increasingly offset the region’s redder rural areas. That made Rankin’s seat another target for Democrats.

While Democrats did manage to flip an open state senate seat in the southern Denver metro from red to blue, Priola and Rankin’s victories prevented the party from doing much to widen its majority in the state senate. In January the balance of power will be 20-15.

“They march to the beat of their own drum,” said former state senator Josh Penry, now a Republican political consultant who runs EIS Solutions. “If Republicans are looking for lessons, if they’re looking for a way to win tough elections, in tough districts, in tough cycles, Bob and Kevin point the way.”

But the future of Priola’s seat may still be blue; because of term limits, this will be his final four-years in the state Senate. After that, the party may find it much harder to hold this district, without such a familiar name on the ballot.