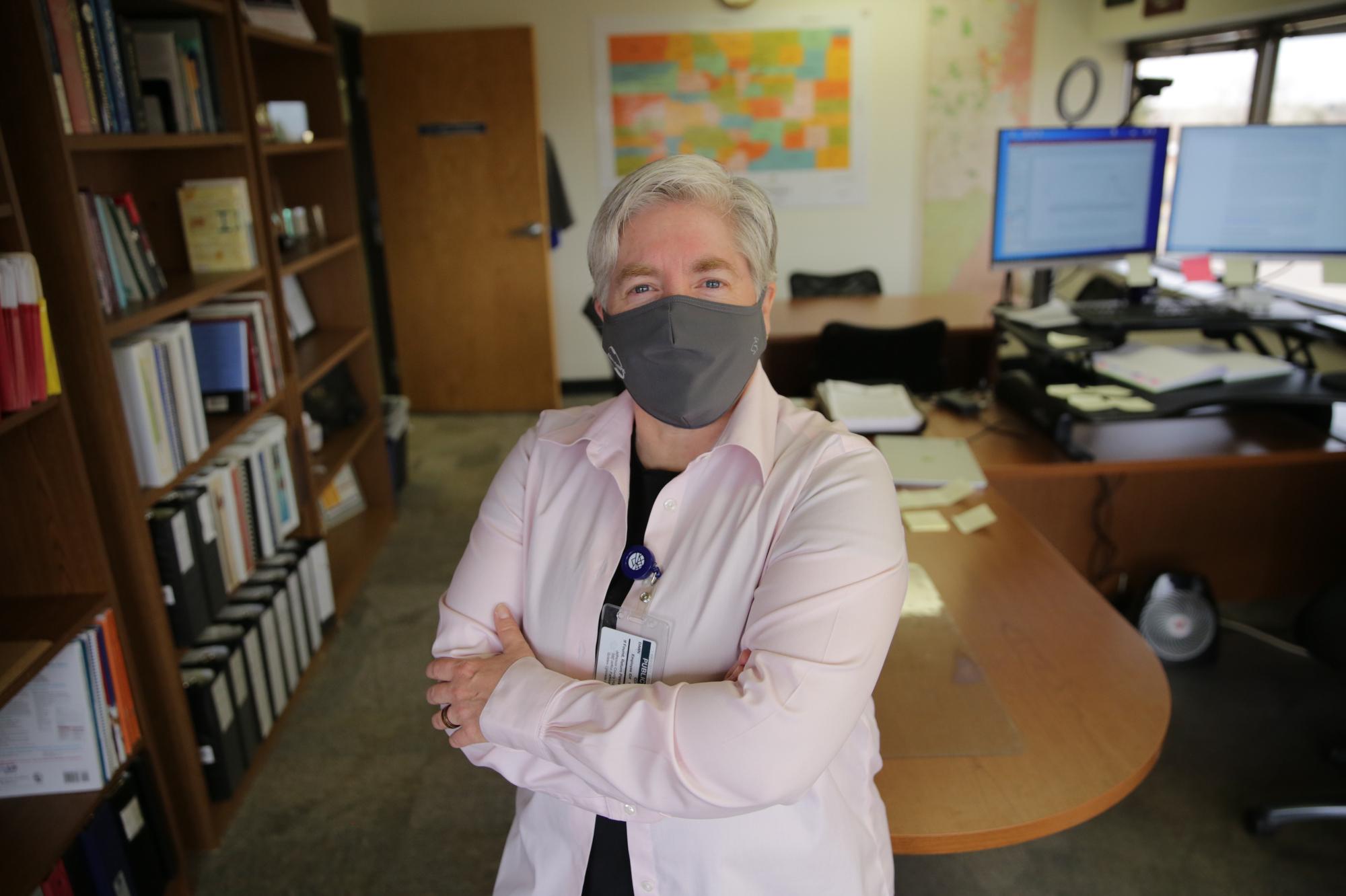

Dawn Comstock thrived as a tenured full professor at the University of Colorado Anschutz in Aurora. She taught. She researched and published peer-reviewed studies on things like concussions and injuries in high school sports. In many ways, it was a dream gig.

Then, the pandemic hit.

“I just felt that I had something to offer and I couldn’t sit on the sidelines anymore,” Comstock said.

Comstock jumped out of academia and into the fray, as Jefferson County’s new public health director. Her move came at a key time. Her counterparts faced threats for their work, with some picketed at home. More than 20 in Colorado, and 190 nationally, have quit, been fired or will leave soon as the pandemic goes on.

Those realities are not lost on Comstock.

“I tend to like a challenge, I guess,” she said.

Last year, as the worst public health crisis in a century hit, Comstock was teaching students the discipline that’s all about how diseases spread: epidemiology.

“We were hearing about the first cases in Wuhan, China,” she said. “We used the data from the different provinces of China to demonstrate how to calculate case fatality rate.”

She and her students watched slack jawed as what had been purely theoretical became the real thing. That’s when she decided to make the leap.

“It just became a growing pull on me, this need to help, this need to do more,” she said.

Trading academia for public health, and new challenges.

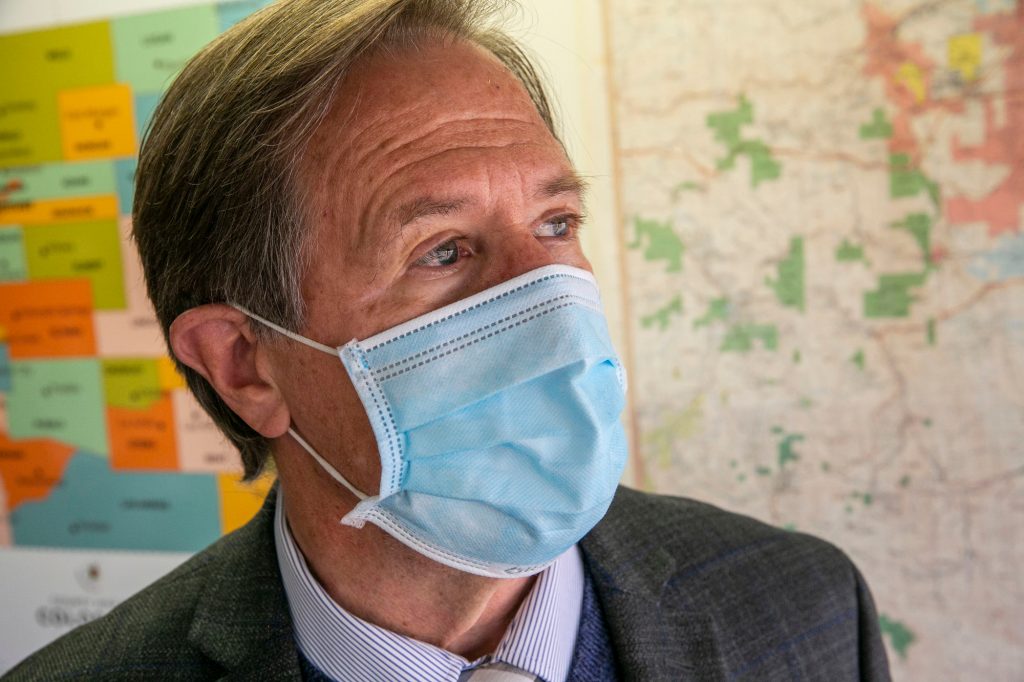

The person she is replacing said she is a welcome reinforcement.

“I think Dawn is an excellent public health person, who loves public health, loves epidemiology,” said Dr. Mark Johnson, a 30-year veteran of public health.

Until the pandemic, he’d spent much of his career dealing with more ordinary things like food-borne illnesses or outbreaks of flu or measles. Then last March, as cases started popping up globally, he told his staff “this is a pandemic. And it's going to hit every county in Colorado. We realized this was the big one and that we were going to have to deal with it.”

Dealing with it meant issuing mask mandates and tough restrictions, like on the number of people who could be indoors in businesses like gyms and restaurants. That led to tensions, most notably over an anti-mask rally and legal fight over social distancing requirements at Bandimere Speedway. Hundreds gathered there over the 4th of July weekend in open defiance of public health rules and a judge’s order.

Johnson said he received threats, but none that were direct.

“I did get threats,” he said. “‘You better watch out, you better watch your step, you're going to lose your job. You better watch your family. You better watch out. We know where you live.’ Those kinds of things.”

Law enforcement deemed them credible enough to add patrols around his workplace and parked a police car outside his home.

“It would be hard to say I wasn’t unnerved, but I think it was harder on the family," Johnson said. "You begin looking over your shoulder more, or you start driving different ways to work.”

Johnson will now continue to work for the county as its chief medical officer. He says top JeffCo leaders supported his department throughout the pandemic. And Comstock got a clear view of the job, since she’s also been serving as a member of the county’s board of health, to which Johnson reported.

“So throughout the whole year, she knew that the stress we were under and the challenges we were facing,” Johnson said.

Dr. Jon Samet too thinks Comstock is prepared for the pressures of the job. He heads CU’s School of Public Health and leads the state’s COVID-19 modeling efforts. He said Comstock’s academic background will serve her well in setting local public health policy.

“I always think it's great to see people jump from academia into practice and back and forth,” Samet said.

Public health work during a pandemic is often personal.

Other local public health leaders say the crisis exposed many struggles and challenges to improve the health of Coloradans. In Durango, San Juan Basin public health director Liane Jollon has herself been a target of protesters over public health restrictions.

“We're happy for the fresh legs and happy to get some subs,” Jollon said. “There's a tremendous amount of work to do in public health in general, regardless of this pandemic.”

Comstock, 54, said she hadn’t personally felt the full impact of the pandemic like many families.

“I've been incredibly lucky. I have not lost a close family member or an incredibly close friend yet,” she said.

But true to form, for her new position, she thinks that may in part be “because I have relentlessly harassed all of my friends and all my family members” about following all the public health guidelines like wearing masks, avoiding large social gatherings and washing hands.

She did recently get some insights about the challenges of getting vaccinated. Her 80-year-old mother-in-law lives in St. Louis and had to drive three hours away to another part of Missouri and back to get her first vaccine shot.

“It's real to us. And we're working very hard at Jefferson County public health to address these issues,” she said, noting supply has increased and many more people are now getting shots.

But “we hear stories like that from right here in Colorado as well."

After the pandemic winds down, Comstock is eager to show the community how important public health still is.

Comstock won high praise from former student Vrishank Bikkumulla. He’s a freshman at University of Colorado Denver and took her epidemiology course last fall.

“I think she would be great for the job,” he said.

During the pandemic, Comstock also worked for the state health department, assisting with the COVID-19 response, including case investigation and contact tracing efforts. After she told students of a job opportunity with the agency, Bikkumulla applied and got a position as a part-time contact tracer.

“It really opened my eyes a lot more to the work of public health, and I think how vital it is in our modern day society.”

Comstock too hopes to communicate to the community how vital that work is. And she says she’s ready for this pandemic to wind down, so she can set her sights on all the other public health battles “to ensure the air you breathe is clean. The water you drink is safe. The food that you consume is healthy and safe.”

“Very few people really kind of stopped to think anymore about clean water until we have something like the Flint water crisis,” Comstock said.

Or about food and restaurant inspections until a food-related outbreak hits. Or about infectious disease control until a pandemic strikes.

Comstock says your local public health department touches nearly every part of your life. That work has often gone unseen, unheard, and definitely unsung. But that was before the pandemic struck.