Faculty and staff are calling for more transparency from University of Colorado Denver administrators about a recently announced $12 million budget shortfall.

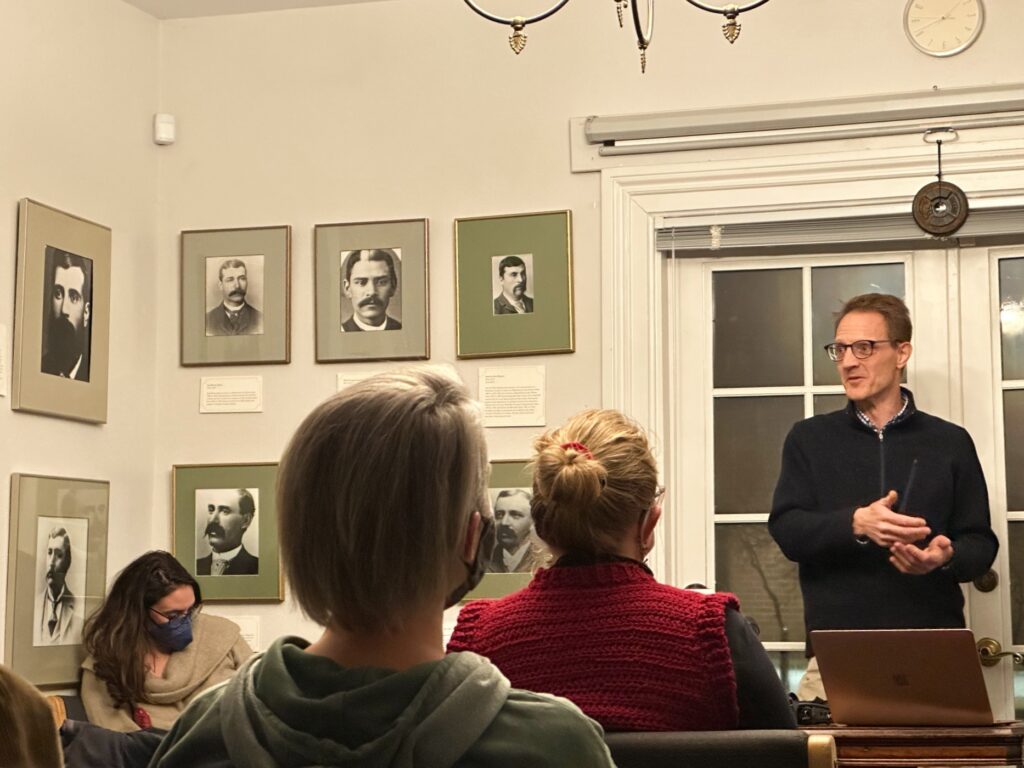

“We have a crisis,” said Marty Otañez, chair of CU Denver’s anthropology department who helped lead a “teach-in” Wednesday evening to highlight employee concerns and questions about the budget deficit. Faculty and staff from the University of Colorado’s other campuses also made a pitch to attendees to join the union, the United Campus Workers of Colorado.

“The current mood is bleak. People are concerned. They're dissatisfied. There's a lot of anxiety.”

An enrollment dip, inflation and the higher costs of doing business have left the University of Colorado Denver with the budget shortfall that must be erased by the 2024-25 fiscal year. Over the next few years, officials at the urban campus will be engaged in a university-wide “budget realignment and growth initiative.”

This year’s fall enrollment at the 15,000-student campus was 1.2 percent under budget. University officials said they can balance that reduction with one-time funds through June next year. The following fiscal year additional cuts will be needed to balance the budget as the university tries to innovate and increase enrollment.

“We need to focus with greater clarity and intentionality on student recruitment, persistence, retention, and graduation, which is core to our mission and the most important aspect of all of our work,” chancellor Michelle Marks wrote in a faculty and staff letter this month.

The university, which celebrates its 50th anniversary next year, said there are no plans for furloughs but some positions may shift and some may be eliminated.

“We need to carefully consider each position on a case-by-case basis,” a website dedicated to the realignment stated. It notes that in the past, some budget cuts were across the board. Reductions this time around will be more targeted.

The university has asked administrative departments to propose plans for 4 percent reductions and school and colleges must plan for three percent reductions for next fiscal year.

“It’s going to be heartless and it’s going to be painful,” said Otañez, who will be involved in deciding reductions in his role as a department chair.

At Wednesday’s meeting, faculty shared concerns about changes already underway. Course sections are being cut, class size caps are increasing, open positions are not being filled. There is also a push to move classes online, and low pay for graduate teaching assistants.

Katy Mohrman, an associate professor in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, said the college is cutting 60 courses on the spring calendar.

“We keep hearing there’s no money, but we don’t hear any more than that,” she said.

Mohrman said she was told the university would be reinvesting in some areas and divesting in others.

“What areas are you divesting from? What does that mean? What does that look like?”

Michelle Comstock, associate chair and associate professor in the department of English said she’s getting emails weekly from distressed staff.

“People are scared, worried they won’t have classes in spring or next year,” she said, adding that students are hurt too, when classes aren’t offered. Lecturers in some departments have been told they’ll only get one class next semester.

The prevailing question at the meeting was, with several years of declining enrollment, why are employees being told about this now.

“I’m shocked we haven’t had this conversation sooner,” said one nontenure-track faculty member, who didn’t want to be named for fear of losing her job. “It makes it hard to plan for the future. Will I have a job in 10 years at this university?”

She didn’t realize when she moved to Colorado to take the job that the state spends the second least in the nation per student. In 2021, it was about 65 percent of the U.S. average. Approximately 75 percent of CU Denver's budget comes from student tuition and fees, and a little less than 15 percent comes from state funding. She’s worried the situation will get even worse, with a coming demographic cliff for college-age students.

Faculty want transparency from administrators, input into budget decisions, an analysis of how much is spent on administration and more state support.

“The structural deficit we’re facing now as an institution is very much tied to state support,” said Keith Guzik, incoming chair of the Sociology department.

Guzik was there to explain to employees the university’s budget system. Some say part of the blame is a new incentive-based budget model that they say penalizes large colleges like liberal arts. They argue that though the college brings in the most money through student credit hours, the system rewards smaller departments that see incremental growth in credit hours.

“The budget model only works if there’s not a crisis,” said Guzik. “We’re in a perpetual crisis. “

Working over the next 18 months, deans and chancellors will identify reductions, innovative ideas and redesigns to save money and plan for growth. The process will involve the whole campus community, along with outside advisors specializing in financial strategy and change management.

The university points to several factors for why it's in the situation it is. It hasn’t met enrollment targets in recent years, state funding for research institutions hasn’t kept up with inflation, and costs for employee benefits and running the university have gone up significantly. The university said it has worked hard to keep tuition and fees affordable, while continuing to pay employees competitively and equitably. Employees will get merit raises this January and beyond, it said.

A special committee starting next spring will identify “academic issues and structures” that are either helping or hindering CU Denver’s growth.

“I know that the next few months — and, frankly, the next few years — will be hard as we move through this process,” Marks wrote in her letter to employees. “By working together, across our campus, we can and will lift ourselves out of this challenge.”

At the same time, the university is working on an ambitious 2030 strategic plan. More than 50 strategic planning initiatives will continue but some initiatives may take longer to achieve, it said. The plan lays out goals for CU Denver to be a nationwide model for teaching diverse learners and erasing demographic gaps in graduate rates. The plan includes an innovation district downtown, featuring a new engineering building where students, faculty and entrepreneurs will interact. It has a goal to increase enrollment by 10,000 students.

Some at the meeting questioned why the university is focused on growing when they believe it should focus on sustaining and stabilizing.

“How do you realign a $12 million budget shortfall?” asked Wendy Bolyard, a nontenure-track teaching professor. “We’re somehow magically going to recruit 1,500 more students a year for next seven years all the while class sections are being cut, favorite and long-term lecturers are being told they are no longer needed, graduate workers stipends, which are already dismal, are in jeopardy.”