Ashley has seen more than most 13-year-olds. More than most people of any age.

She’s walked alongside busy, truck-laden highways and through hot, humid jungles filled with smugglers, criminal gangs, and snakes. She’s crossed through at least five countries. She’s taken buses that took her to people who made her family pay or they’d be detained or kidnapped.

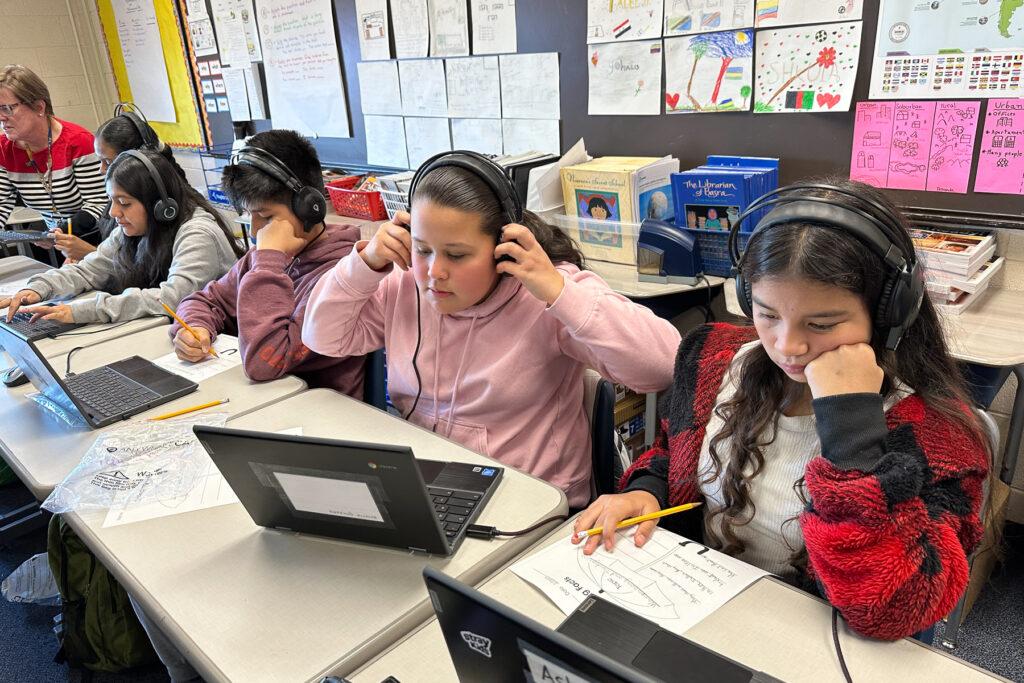

And now the Venezuelan teen with long curly brown hair is sitting, headphones on, at a desk in a southeast Denver classroom.

She’s listening to a story about the year 1621. It’s the story of how the Wampanoag people, using 10,000 years of accumulated knowledge, taught other newcomers to this continent, pilgrims, how to survive a harsh winter. She listens to the pre-Thanksgiving lesson in English.

“There are times when I don't understand, but I try to get a bit of what they are saying and then get an idea about the topic,” Ashley said in Spanish. But she said she’s just happy to be here, safe and learning, though she worries about her grandmother left back in Venezuela with an injured leg.

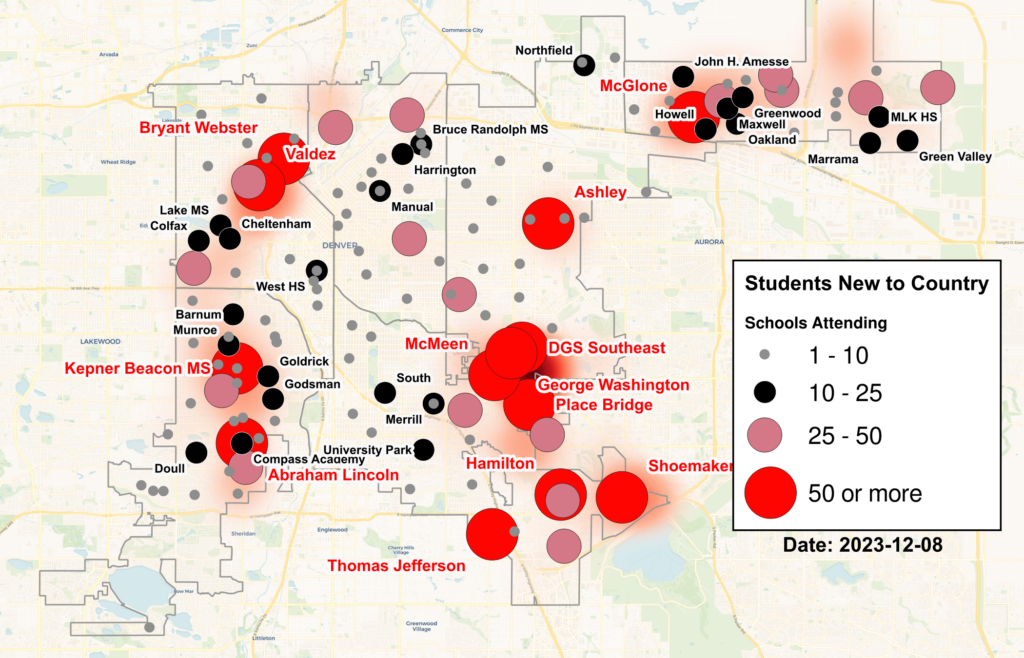

Ashley is one of more than 2,200 students who have enrolled in Denver Public Schools, along with hundreds more in other Colorado school districts, since the summer. An estimated 6,000 new migrant students have enrolled in Colorado schools since the summer, according to a tally of a dozen districts that were contacted by CPR. Some schools, lacking enough interpreters and bilingual teachers and aides, are struggling to meet all the needs of the sudden and rapid influx of migrant children.

“We’re seeing really full classrooms, and especially in a lot of our bilingual program schools, seeing in some cases classrooms that are so full, they actually can't take any more students,” said Adrienne Endres, DPS’s executive director of Multilingual Education.

Endres acknowledges that the situation is stretching the district’s resources but she also sees it as an opportunity to “do differently and be different together.”

DPS is better suited than many districts to meet the needs because it has so many bilingual programs. The district also has newcomer centers that offer small class sizes and are dedicated to catching students up on content and offering intense English.

For the most part, so far, schools are adjusting.

“This is often painted as a crisis, but these kids are bringing smiles and hugs and joy to our school, and so we're really glad to have them here and really glad to be able to support them and their families,” said Nadia Madan-Morrow, principal of one of the impacted schools.

As families search for cheaper housing, school districts outside of Denver are enrolling migrant children

While Denver Public Schools has enrolled most of the new children by far, Aurora Public Schools has enrolled 1,600 since July, with most from Venezuela, Colombia, Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala.

Of the districts that responded to CPR’s inquiry, Adams 12 Five Star has 600 students who’ve been in the country for two years or less. Of those, 225 have arrived since Aug. 1, compared to 183 in 2022. The district has also opened its first newcomer “school within a school” center. On the first day of school, 30 students were enrolled. Now there are about 100.

Westminster has 230 new migrants compared to 150 at this time in 2022. Mapleton has had about 80 new arrivals. Greeley-Evans District 6 has seen a slight increase from last year – 228 newcomers over 193. 27J in Brighton said it has very few new migrant students, and far south in Durango only 29 newcomers are enrolled.

Several mountain districts have reported more students from Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, and Central America, but some have already transferred out, unable to find places to live.

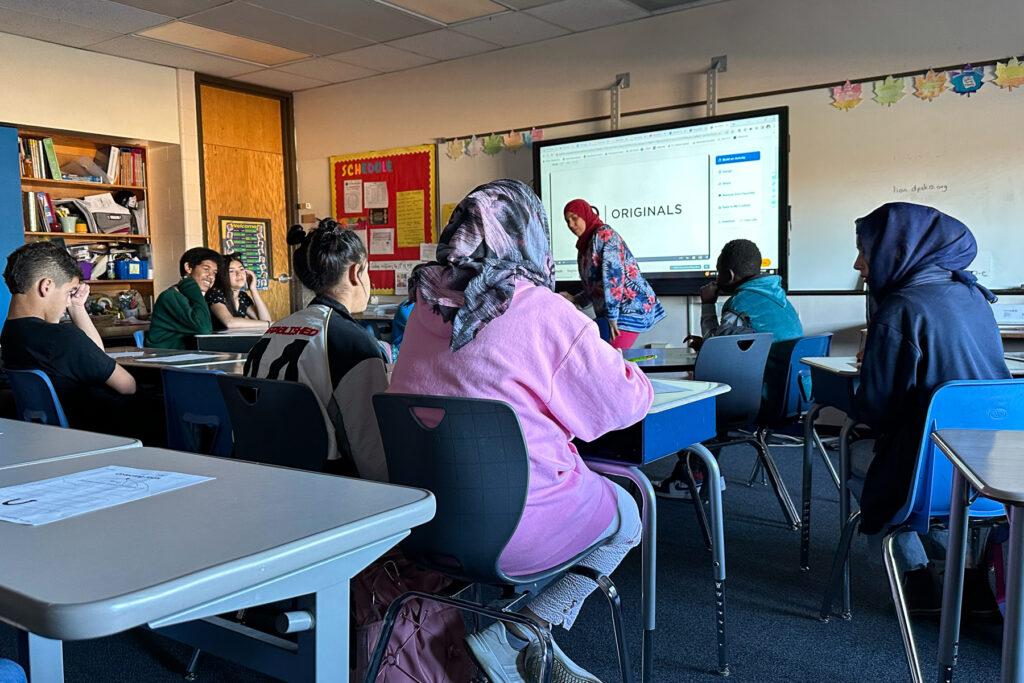

One Denver school that is more prepared than most for the new arrivals is Place Bridge Academy

The preschool through eighth-grade school is designed to provide special programming for immigrant and refugee children. Forty-seven languages are spoken in the school. But even Place Bridge had to make a series of changes to meet all the needs of new arrivals like Ashley.

On a tour, Madan-Morrow points to what used to be just a library. Now it serves as a nook for math intervention with reading intervention in another area.

“We’re working on trying to get something to break up the sound because it’s noisy in there right now,” she said.

Every bit of space in Place Bridge Academy is full right now.

“Frankly, in schools, we were really caught off guard,” said Madan-Morrow, recalling how educators watched early news coverage of migrants arriving in Denver but didn’t expect the number of children that would be among the arrivals.

Over 100 more students than the school expected showed up this fall.

It was rough at the beginning. There weren’t enough teachers.

Literacy teacher Carmen Kuri-Moeller said the teachers who spoke Spanish could immediately start modeling behaviors, teaching students how the U.S. school system works. But when the kids went to classes like art or P.E. — classes that typically have more than 30 kids — teachers often didn’t know Spanish.

“Things were going crazy,” she said. “Some teachers were overwhelmed because they didn’t know how to communicate and they didn’t understand the background of the students.”

School leaders quickly realized they not only needed new teachers but would have to reconfigure classes because something was different about many of the new students.

“Our students who are newly arrived from Venezuela, many of them have had very long journeys to get here, about two years to get here, so we have some students who have never been in school, we have some students that haven’t been in school for several years,” said Madan-Morrow. “It’s been an all-hands-on-deck type of a situation that’s required a lot of flexibility and out-of-the-box thinking.”

School leaders hustled, using every connection they had, and hired five more teachers, most from Spanish-speaking countries. Madan-Morrow hired a health technician to help the nurse because there are many students with serious health needs.

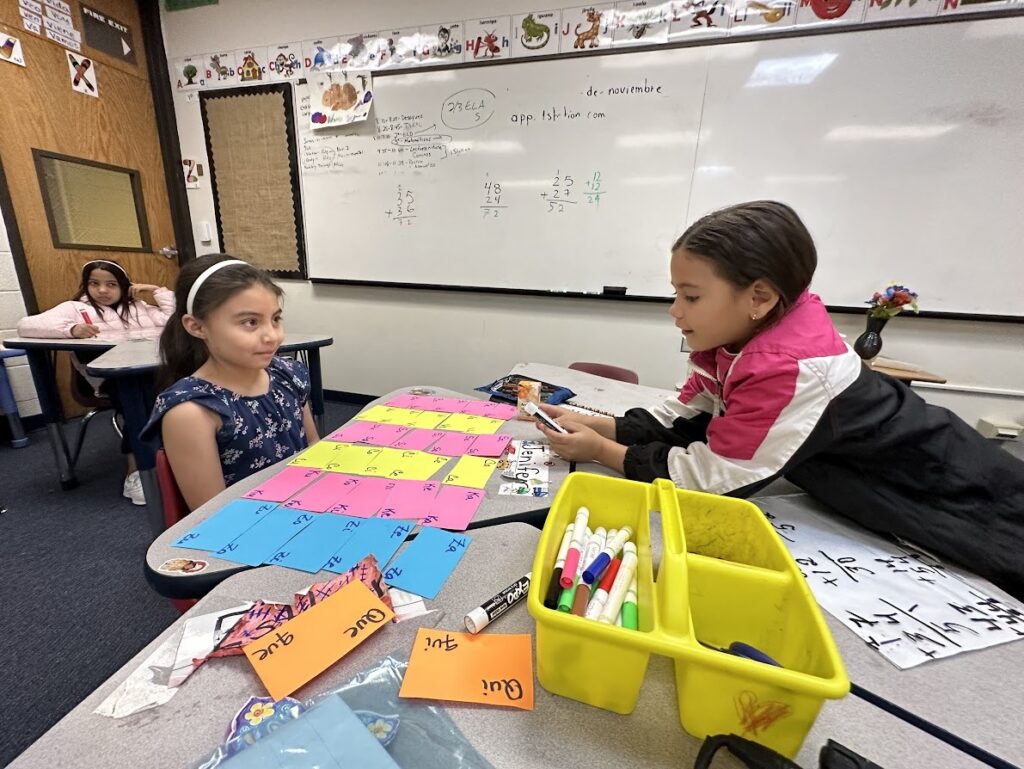

Siete, ocho, nueve, diez … We put it here, remember?

Third-grade teacher Rene Noris Fernandez, who's a new teacher from Mexico, counts out numbers on his fingers along with a student and then asks if she remembers what number to “carry” over to the ‘tens’ side.

He sits briefly with each child individually, helping them make sums out of two double-digit numbers — in Spanish. Research shows the more kids can get up to speed academically in their first language, the more quickly they’ll learn English. The class is a combined second and third-grade bilingual classroom.

“Ba” “be” “bee,” said a 9-year-old boy as he learned the letter “b” with vowels. The aide said the boy, tentative and soft-spoken, is new to the country from Venezuela has never been to school before, and doesn’t know how to read. Noris Fernandez said it’s the situation with other third graders in the class.

“They don’t know letters, they don’t know letter sounds and so that’s why we’re going over this so they can start to learn how to read,” he said.

But today, every kid is busy, working at tables, helping each other, and learning.

The basic needs of students are significant

Many new arrivals came with no winter coats, hats, or boots. Sometimes teachers fill those needs. Classroom aide Lekbira Bensabahia shows boxes of boots that teacher Janet Taggart has bought for her seventh and eighth graders.

“She (Taggart) has a good heart,” said Bensahahia, patting her heart. “She gives them coats….there are gloves and hats here!”

Taggart deflects the attention, saying there’s a classroom economy where the kids earned ‘money’ for doing extra work, and that helped make the purchases.

In the hallway, project community coordinator Marisol Chavez pushes a cart piled with a recent donation of 900 pairs of gloves and hats.

“One hat, one pair of gloves!” she calls out to students who crowd around the cart.

The students smile and thank her.

Some kids live in shelters. The city gives families 37 days in a shelter and then they must find a place to live. Some have secured apartments with two, three, or four other families. The school houses one of the district’s six community hubs to help meet family needs. There’s a waitlist to access services like food and clothing. The Denver Health Clinic at the school has a waitlist for students needing mental health services.

That’s because the journey to the U.S. for some was traumatizing

When we entered the jungle, it was like a hell. We spent six days in that jungle. Each time we took a step we felt farther away each time. (From a student essay)

For children who need it, Place Bridge Academy has more support services than most schools: two school counselors, a psychologist, and two therapists in the building. Social worker Jessi Aragon said some kids just need help with the routine and the expectations of school that they aren’t used to, while others may need some basic skills to process what they’ve been through.

“Giving them a safe space, they are allowed to feel whatever they want to feel — if they are sad, guilty, angry, just normalizing that, giving them a safe place to feel that,” she said.

Sometimes the students can be triggered quickly. They may be very excitable or they shut down, head down on the desk. Knowing many have experienced trauma, Taggart navigates and negotiates. Sometimes the classroom aide will walk a few laps with a student around the school.

You got on the bus afraid that you would end up sleeping on the street without knowing what could happen. If you ran out of money you had to find a way to get it. (from a student essay)

“All my students can trace on the map and tell you the route that they took and how many months it took them to walk here,” Taggart said.

Ashley said the jungle part of the journey was easy. Indigenous guides who live in the jungle took care of them and ensured their safety. She said the hardest thing was the utter fatigue of walking such a long distance.

“First of all, thanks to God. It was dangerous especially in Mexico and Costa Rica because bad people can kidnap you, and what I recommend to others is to always have God with you,” she said.

Ashley said the journey changed her. She said she feels braver now. Bolstered by her experience, she wants to complete school so she can become a pediatrician.

Taggart knows the level of English her students will need to succeed in high school is high

She doesn’t want them dropping out in ninth grade.

“I feel such a strong need to help them move and push them to get as much as they can in the one year they have newcomer support,” she said.

Her students in the newcomer program get extra support for one year. Newcomers are students who’ve had interrupted schooling and also limited skills in both English and their native language. There were so many Spanish speakers this year they had to split Taggart’s class in two and create a new bilingual newcomers’ class.

“I love this country … I love learning English every day and my parents are proud of me.” (from a student essay)

Some have already left after their families found more permanent housing farther away. At the time of publication, 335 students have already moved out of their schools, district-wide, as their families have found more permanent housing.

Kuri-Moeller said smaller class sizes and more time with students, and teachers have been able to establish connections. And she said students are learning and changing.

“It’s getting better.”

- Interview: Venezuelans who migrated to Colorado can start to apply for temporary legal status, but many say it’s an inadequate solution

- With shortage of local labor, farmers and advocates want Congress to create incentives for migrant farmworkers

- Interview: Here’s why so many migrants have come to Colorado, and what the next steps could be