A committee tasked with handling the future of a former Indigenous boarding school in Grand Junction is considering a plan that would see the property transferred to Tribal governments.

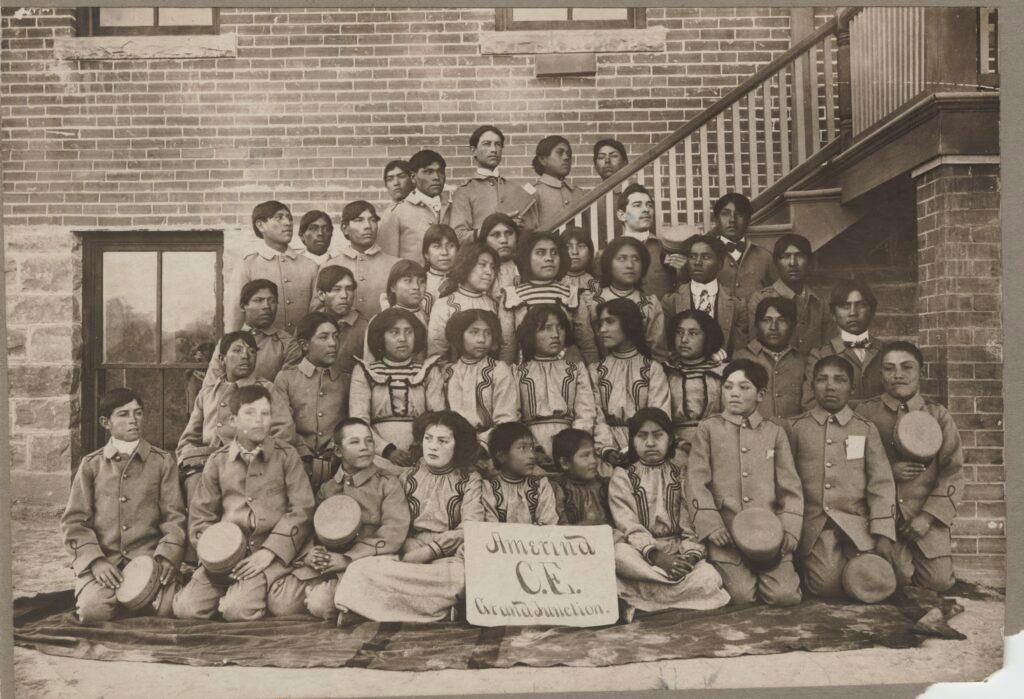

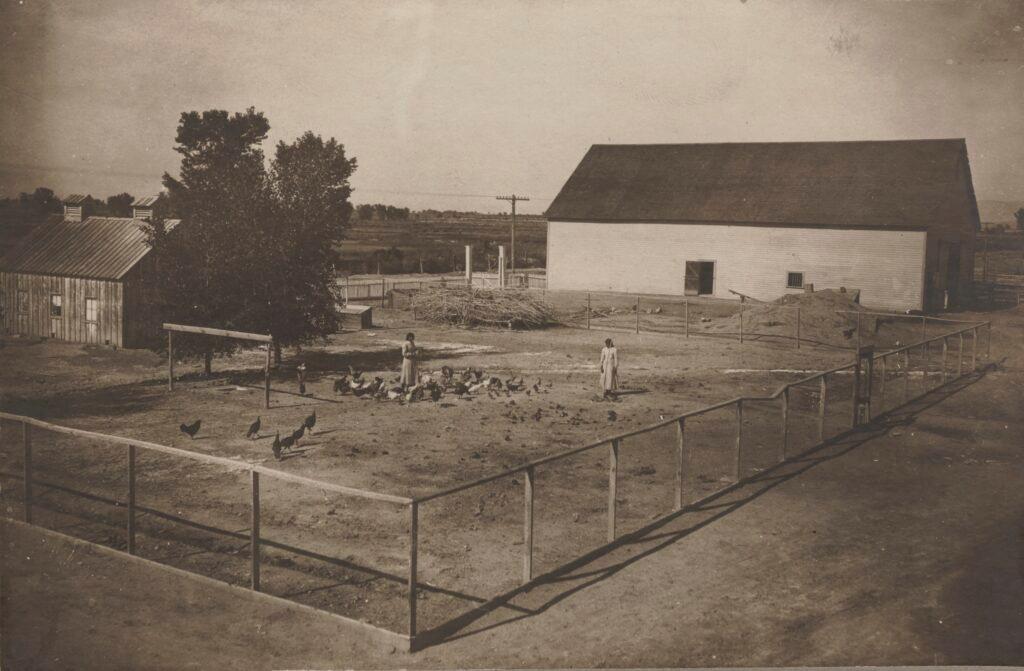

The Grand Junction Regional Center, as it is referred to presently, was previously home to the Teller Institute, which was also called the “Teller Indian School,” which operated from 1886 to 1911 and brought in children from across the west. A few years after the Teller Institute closed, the property became a state facility for housing people with developmental disabilities.

In recent years, more attention has been drawn to the historical wrongs of the federal boarding school era, which was tasked with stripping children of their Tribal identity. In many cases, grave sites of children who didn’t survive the process have been found at locations of old boarding schools.

Prompted by that, lawmakers in Colorado passed legislation that commissioned a state report on the three schools located in Colorado, and outlined a way for that property to be vacated and either sold or transferred to “a state institution of higher education, a local government, a state agency, or a federally-recognized tribe in Colorado.”

In Colorado, the Ute Mountain Ute and Southern Ute are the two federally-recognized tribes.

At a meeting earlier this month, members of the Regional Center Conceptual Redevelopment team discussed the possibility of the land being transferred to the Tribes. During that meeting, Crystal Rizzo, cultural preservation director for the Southern Ute Tribe, made the case for transferring the land to the Tribes.

“This was built specifically, initially, for Natives and I think the use for that — or maybe no use for that — should be up to the Tribes,” Rizzo said. “And I would really argue for the land and the space to be returned to the two resident tribes and then also include the Ute Indian tribe of Uintah and Ouray, because that's their traditional homelands.”

Rizzo was among a group of officials that included Tribal, county and state representatives who were discussing the next steps for the project. Grand Junction City Council Member Anna Stout agreed the Tribes should be the groups leading the effort.

“I don't think any of us feels that this shouldn't go back to the tribes. So is there any reason that we're not starting from that presumption?” Stout said.

Stout added that there have been calls in the past for the city to take over the land and use it for housing or homeless services. She said city officials were not on board with this line of thinking. In addition to preferring Tribal ownership, Stout said it would send an unfortunate message about the historic uses of the property.

“Frankly, I think it would dishonor the property, the land itself, because the last thing I think we want to do is continue to have this be a place where the community's perception is this is where we put people to not have to deal with them,” Stout said.

Mesa County Commissioner Janet Rowland echoed Stout’s position, suggesting that Mesa County, Colorado Mesa University and the city of Grand Junction turn the process over to the state to work with the tribes the rest of the way.

The land is currently owned by the Colorado Department of Human Services, which manages the Regional Center. They recently completed a yearslong effort to relocate the remaining adults with disabilities who were housed there into community housing, the model that is preferred to so-called “institutionalization.”

Before moving forward, officials must first locate any human remains on the property, a project currently spearheaded through a Colorado School of Mines Investigation. A grant-funded survey of the property has scanned the land, and the data is set to be analyzed in the search for possible remains.