This story is a part of Understanding Southern Colorado's Groundwater, an occasional series from KRCC about groundwater resources. Read more stories here.

As drought and demand affect water resources around Colorado, groundwater from aquifers is also part of the water supply equation. Understanding what aquifers are, how they function and where they are is part of the bigger water resource picture.

KRCC’s Shanna Lewis spoke with two hydrogeologists: Lesley Sebol, groundwater program manager for the Colorado Geological Survey and Colorado Geological Survey senior researcher Matt Sares, who previously led the hydrogeology section at Colorado’s Division of Water Resources.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

KRCC's Shanna Lewis: What is an aquifer? Is it like a big underground lake that wells tap into?

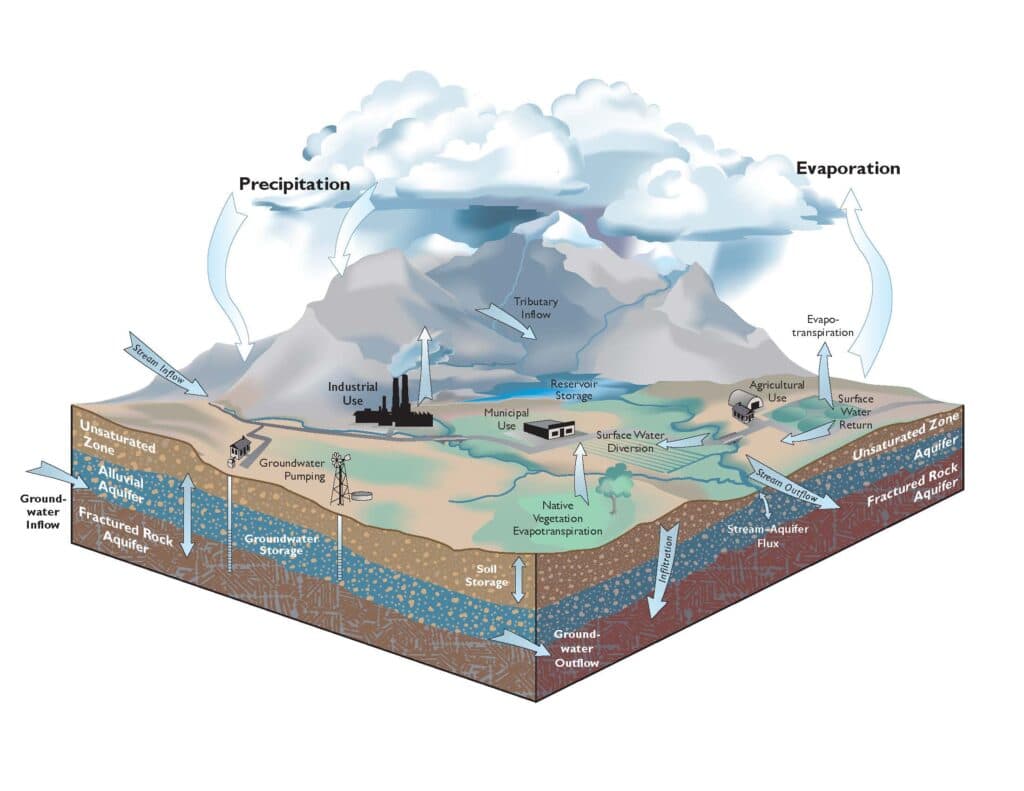

Lesley Sebol/CGS: I know a lot of people think of it as a river underground or big lake or pond underground, but the reality is it's water that's entrained in sediments or rock. What happens is precipitation, rain or snow, infiltrates into the ground. On the ground surface there is loose sediment like gravels, sands, clays, silts. The water will continue to percolate down into the subsurface and then eventually it reaches a point where the sediment becomes fully saturated and at that point it's considered the water table and that's where your first aquifer would be. Beneath that you have layers of rock. You can have different kinds of rock, but in general, think of rock aquifers as being fracture flow dominated, which means that the water's flowing through fractures in the rock.

Lewis: How long does it take for the water to get into the aquifer?

Lesley Sebol/CGS: It depends on how deep it's going. It can be very quick if it's very porous – in the order of days. But it can be weeks, it can be months, it can be years. It depends on how deep it’s going and how tight the material it's flowing through. Sometimes it can be decades or millennia, so very, very old. The older water usually isn't as good as the fresher younger water.

Lewis: How do aquifers intersect with rivers? Is surface water (like rivers) completely different from groundwater?

Matt Sares/CGS: Surface water and groundwater are connected. There's a couple of different ways to see that connection.There's alluvium (sediment deposited by flowing water like streams or rivers) at the surface that depends on rainwater or snow input to recharge those aquifers.That's a really direct connection to the amount of precipitation we get in Colorado. Those aquifers are generally right next to streams and so water from those aquifers are continually coming into the streams. As you go out east, there are also bedrock (aquifer) units that come up from depth and intersect our rivers and contribute some water to those rivers as well.

Lewis: Do all aquifers eventually run into rivers?

Matt Sares/CGS: As I said, all surface water is connected to groundwater and vice versa, but there are some geologic units that are relatively tight and don't transmit water at a great rate to surface water. There's a legal definition (for non-tributary water) in Colorado and that is if you are pumping a well and your well pumping depletes the water in a stream by more than one-tenth of 1 percent of the pumping rate, then you are tributary to that stream. That's a really high bar actually to be declared non-tributary. But there are deep aquifers that are a long way from a stream that if you pump in this aquifer at this time, the impact isn't going to hit the stream for hundreds of years and so those are the types of aquifers that are identified as non-tributary.

Lewis: Are primary groundwater sources affected by drought?

Lesley Sebol/CGS: Water is recharging into the aquifers and when there’s a drought, there's less water going in. Now in shallow alluvial aquifers that you see a more direct connection because the recharge is happening near the surface. So when you don't have that water going in, the groundwater table will start declining. Especially if you're heavily pumping it, it'll go down pretty fast. But in the bedrock aquifers, droughts may not be seen for a very long time because there's a delay. You'd need a very long-term drought to see a noticeable impact. When you're down deep in the basin, you're more likely to be impacted by how many wells are tapping into that aquifer.

- Groundwater - Colorado Geological Survey

- Colorado Groundwater Atlas

- Groundwater Resources | Colorado Water Knowledge

- Groundwater - Water Education Colorado

- Designated Basins | Division of Water Resources

- Colorado Water Science Center | U.S. Geological Survey

- Want to drill a well for your home? Some rules in Colorado might surprise you

- Many people on the Front Range depend on water from the Denver Basin. But the underground supply isn't infinite

- Study offering free well testing for homeowners in Otero, Bent, Prowers and Kiowa counties for certain contaminants