The First Union Depot: 1880 To complete Walter S. Cheesman’s dream, Kansas City architect William E. Taylor was hired in February 1880 by Denver’s four railroads and Jay Gould, a New Yorker who financed the project, to develop plans for one terminal station to serve them all. The architectural plans were ready on March 20, 1880. Less than a week later, the Union Depot and Railroad Company of Colorado began construction on the new terminal. Ground was broken on the foundation of the new depot on May 10, 1880, after ninety-six lots were purchased for just under $100,000, while another $164,000 was paid to constructor James A. McGonigle of Leavenworth, Kansas. Architect Taylor chose the Italian Romanesque style for this grand depot to be built at the far end of town. 002 Local materials, such as sandstone from Manitou Springs and stone from Morrison, were used. Rhyolite, a rose-colored volcanic stone, was chosen as one of the building materials because it weathers well. The Molly Brown Mansion and Carriage House on Pennsylvania Avenue, Castle Marne Mansion on Race Street and two churches—the Trinity Methodist downtown and the First Unitarian at Fourteenth and Lafayette—were all constructed using rhyolite quarried just south of Castle Rock. 003 The new depot opened on June 1, 1881, as the largest building west of the Mississippi and was not only significant in size but also in cost. Compared to the construction costs of the county courthouse ($360,000); the Windsor Hotel, complete with fine furnishings ($400,000); and the Masonic Temple ($250,000), the depot’s construction costs were significantly higher, reported as between $450,000 and $525,000.

A Leadville mine superintendent, headed to Chicago, purchased the first ticket from the newly opened depot. The Second Structure: 1894

A fire caused by wiring for the ladies’ waiting room chandelier quickly spread to the second floor at the southwest end of the depot. Although the electrical spark was the initial cause of the March 18, 1894 fire, there were many other contributors to the total damage. Flames spread quickly as the conflagration ran along the electrical wiring that filled the garret (attic/loft space under the roof) running the entire length of the depot.

Baggage and express men quickly moved luggage, over eight hundred trunks, as well as mail and express baggage, out of the way. Railroad clerks tried to save records and office equipment, either by carrying the equipment to a safer place in the depot or, on the other extreme, recklessly tossing papers out the window. Flames could be seen burning through the tower framework. Lack of water pressure severely hampered the Denver Fire and Highland Hose No. 1 firefighters as they tried to put out the blaze. Flames weakened the framework and support for the 165-foot clock tower. The weight of the Castle Rock lava stone clock tower eventually caused it to fall through the second floor, crashing into the Rio Grande dispatcher’s room below. The Barkalow Brother’s barbershop and the dining and lunchrooms in one of the depot’s wings were losses. Smoldering pies were found on the lunch counter, but the cash registers were salvageable.

The property damage, primarily in the southwest end of the structure and the second floor, was reported to be between $125,000 and $200,000.

Van Brunt and Howe of Kansas City were selected as the architects to rebuild the center section of the depot after the fire, reusing existing walls that were not damaged. The replacement tower was designed in the Romanesque style with a lower roofline for the wings. The central clock tower again would have four fourteen-foot-diameter clock faces for the public’s viewing but was about forty feet taller than the previous tower. Construction was completed in about a year, and the building would remain in this form until it was demolished for the larger third structure. Blizzards

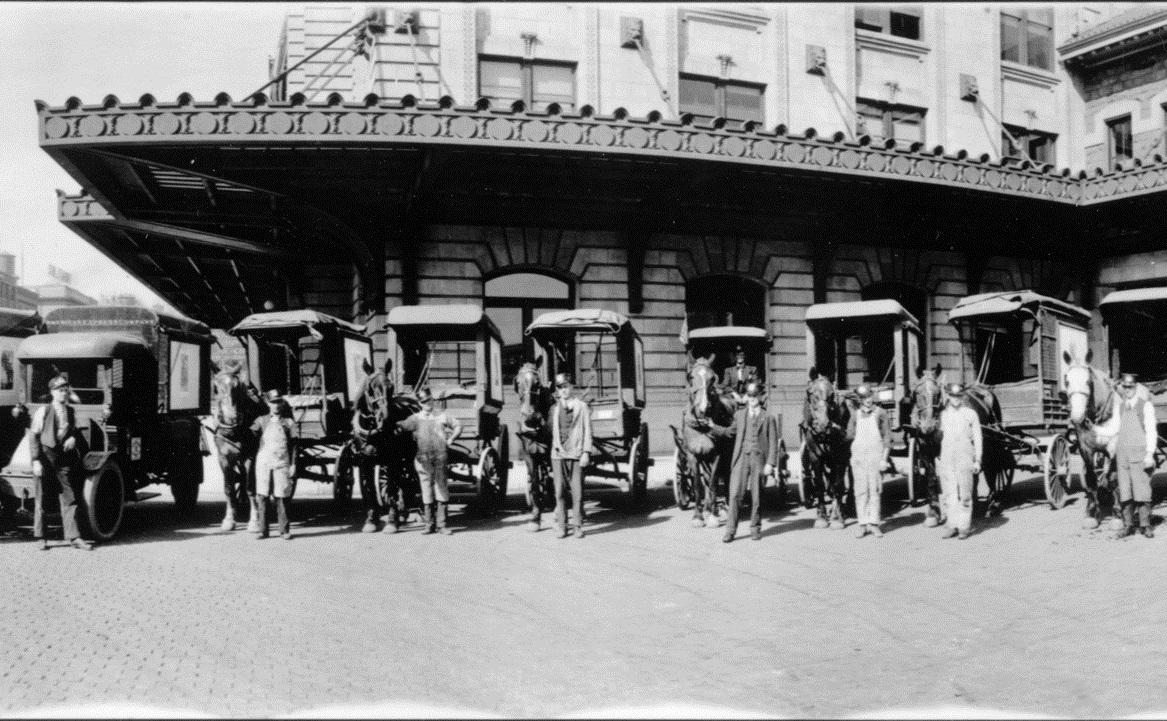

Denver’s largest snowstorm to date came in the first five days of December 1913. During that early December snowstorm, 45.7 inches fell. Cleanup and snow removal took almost as many days. Snow was shoveled into horse-drawn wagons and dumped in Civic Center Park. On December 4 alone, Mother Nature dumped 63.0 inches on Georgetown, just west of Denver. This snowstorm closed down the depot, but not for as long as other businesses in the city. The snowstorm had a tremendous impact on the city’s infrastructure as most roads were blocked by drifts.

Headlines for the Denver Post on December 5, 1913, read, “Denver in Mantle of Shimmering White, Stops Activity and Everybody Jollifies.”

The City Auditorium, jail and movie theaters all gave shelter to those who were stranded. As it was for the trains, the streetcars were halted. Anyone needing work could help the Tramway Company with snow removal for $3.50 per day. Rain and More Rain

As had happened before in Denver’s early history, a heavy rainstorm on July 15, 1912, caused Cherry Creek to rise and begin flooding the city. Carts were used at the depot to move baggage, mail and express packages off the flooding floors. The basement flooded with as much as two feet of standing water. Train passengers waded through the muddy water to higher ground or were trapped at the depot until the water subsided.

The biggest flood happened twenty-one years later when, south of Denver, the Castlewood Dam broke, sending a wall of water into downtown Denver. Water flowed into the station’s large waiting and baggage rooms, filling the passenger and baggage subway system and basement areas. The high-water mark in the basement of Union Station was six feet. Although with pumping equipment the employees were able to clean up and reopen rather quickly, the station’s damages exceeded $14,000. The Third Structure: 1914

Soon, the increased population and travelers outgrew the 1894 structure and rail yards. By 1912, Denver needed a bigger station with expanded passenger platforms and baggage subways and a larger waiting room. Several plans for a larger depot were offered for consideration, including relocating and building in the vicinity of Eighteenth or Nineteenth and Larimer Streets or near Colfax, Champa and Speer Streets. Costs prohibited such relocations. The least expensive proposal was to work with the original building at its current location.

Denver hired Gove and Walsh to design the third and final center portion of the depot. Aaron Gove and Thomas Walsh were the designers of many warehouses and commercial buildings in lower downtown (LODO), such as Morey Mercantile Warehouse on Sixteenth Street, Littleton Creamery, Beatrice Warehouse, J.S. Brown Mercantile building on Eighteenth Street and the Edward Wynkoop Building/Spice Warehouse.

Popular from 1893 to 1915, the current design of the depot is considered Beaux-Arts Classic, the same style as the New York Grand Central Terminal. The style is made up of symmetrical coupled columns with baroque details. Architect J. Jacque Benedict, the first architect to be trained in Beaux-Arts, designed many fine Denver homes in this style.

Demolition of the old central portion began in September 1914. Passengers were redirected through the station, and railroad offices were relocated to the wings while the twenty-year-old stone clock tower (post-fire) was dismantled.

Granite obtained from Argyle Quarry, near Foxton, in South Platte Canyon was used.

Foundation walls and steel erection began before the year’s end. In early January 1915, the old center section was completely excavated, allowing the first floor, 475 cubic yards of concrete, to be poured. The exterior terra-cotta walls reached third-story height two months later.

Interior scaffolding was erected in April to allow lathing and plastering of the main waiting room. By May, marble floors had been completed for the restrooms and barbershop. After the roof was completed in early June, the main waiting room plastering began. Belgium black marble was the chosen stone for the ticket counter, trimmed in Yule marble. The American Fixture Company furnished and installed the main waiting room seats.

On April 1, 1915, the Denver Union Terminal Railway took over the station from the former owner, the Union Depot Railway Company.

All the while, new track was being laid in the yard. The new tracks were connected to the existing main track, and the entire roof of the center section had been completed by June 1915.

The public was able to use the new waiting room by Halloween 1915, but work continued on the express and baggage subways and remodeling of the baggage room. By December, over thirty thousand feet (fourteen thousand ties and 761 gross tons of CF&I rail) of track had been laid, and both the new express and baggage subways, lined with white enameled brick, were in operation.

General contractor Stocker & Fraser, along with other subcontractors, built the 1914 center section. Labor, material and furnishings for the new center section exceeded $3.8 million. From September 1914 until January 1915, the old center section was completely excavated, approximately eighty-five feet from the roof to the bottom of the footing, with some material recycled and reused for the new ninety-seven-foot expansion of the express rooms on the east wing. Each floor of terra-cotta walls took one month to erect, using over nine hundred tons from the Terra Cotta Company.

The new center section was constructed with terra-cotta that was textured and colored to look like granite. Granite from near Dome Rock was quarried for the front face, while stone from Fort Collins was used for the back-track side of the station. Lyons provided the red sandstone.

Although the exterior sides of the new station followed the pattern of the trackside and front entrance, only the rear and front clock faces were used.

The original 1880 wings with their 1894 lower roofline flank either side of the new central section. The interior clocks, at opposite ends of the waiting area, were bordered by marble slabs with adjacent plaster scrolls. A master control system was designed to synchronize the interior clocks to ensure that passengers would not miss their train departures.

The Sixteenth Street viaduct had to be rebuilt to allow trains to pass beneath it, with subways for the passengers, mail, express and baggage underneath it all.

The new look of the station warranted a new name, so the new owners renamed the terminal Union Station, as we fondly refer to this grand historic landmark today. Reprinted from Union Station in Denver by Rhonda Beck with permission of The History Press, Charleston, South Carolina. Copyright (c) Rhonda Beck, 2016 |