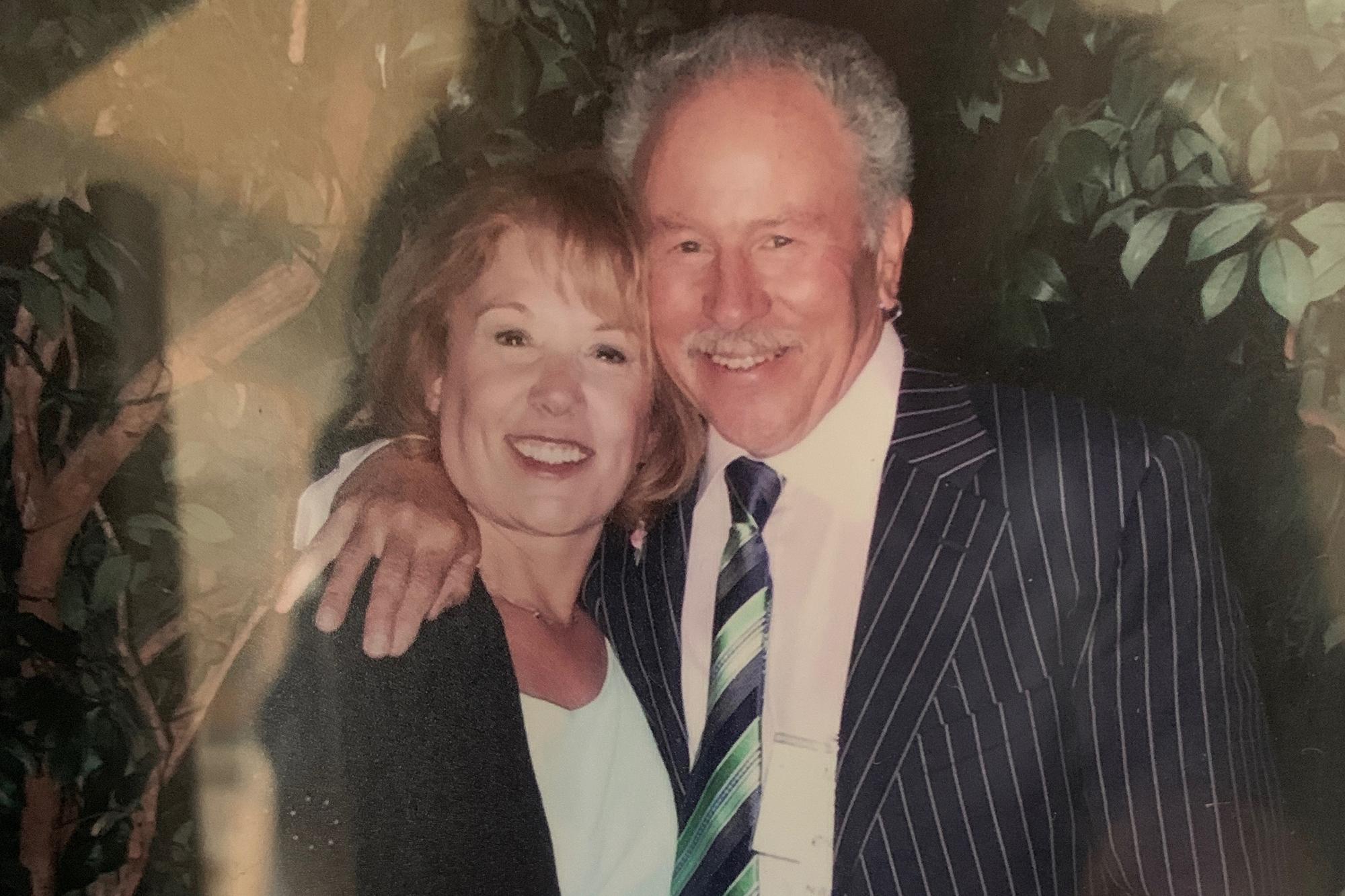

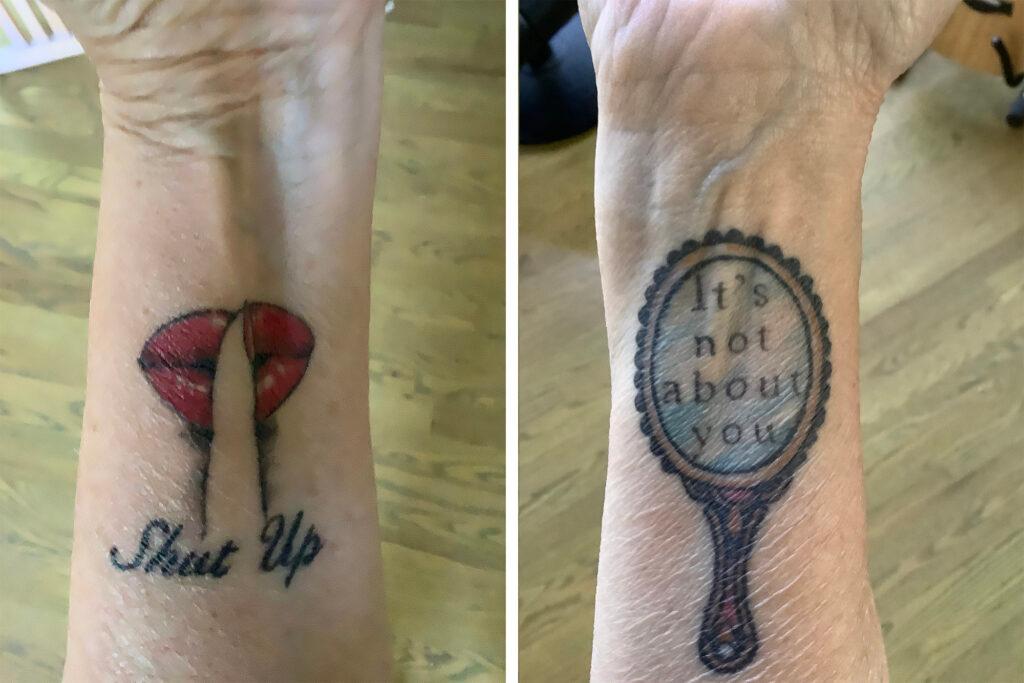

When Jaye Kephart gets frustrated by her husband, she looks at the tattoos on her wrists.

“Shut up,” instructs one.

“It’s not about you,” says the other.

Jaye’s husband, Mike, suffers from a form of dementia called Lewy body. She cares for him at home. The tattoos remind her not to take offense when he forgets something or makes an unkind remark.

“I need to remember not to take it personally,” she said.

Those reminders are needed more frequently during the pandemic, which has been hard on people with dementia, and their caregivers. Jaye and Mike felt isolated before, but at least they could get out of the house to run errands, go to exercise class and see friends. Mike went to a day center once a week. Now, because of fears of contracting COVID-19, all of that is gone.

“I mean, I can't have anybody in, and then if I did have somebody in, where am I going to go?” Jaye said. “Am I going to go sit in the bedroom while they spend some time with him? I can spend time in the bedroom anyhow. So it's definitely different, and difficult.”

It’s not just the isolation. Shutdowns can make dementia worse

Lewy body is the second-most common type of dementia after Alzheimer’s, which afflicts more than 76,000 people in the state, according to the Alzheimer’s Association of Colorado.

For many, things got worse when shutdowns forced a sudden change in routine.

“People with dementia, like Lewy body and also Alzheimer's, are looking for a routine so that they can be successful in their day,” said Amelia Schafer, executive director of the Alzheimer’s Association of Colorado. “They rely on it because they're not able to form new memories. To be able to form new routines is really, really challenging.”

Emotional outbursts are a common reaction. That’s what Denise Bandel of Broomfield has seen in her mother, whose assisted living facility shut down most activities, communal meals, and visiting hours in the name of safety.

“I'd say after a couple of weeks of my mom being very isolated, there would be days where they would call and say my mom's crying and they don't know why. And she couldn't tell me,” Bandel said. “But the tears and the crying have become almost a daily event. So emotionally it has affected my mom greatly.”

Dementia sufferers often lose the ability to regulate their feelings.

Mike Kephart is experiencing increased delusions, which are typical of Lewy body disease. His wife Jaye said that since social distancing began, her husband has started seeing workers in the house who aren’t there.

“He even wears his mask sometimes all day in the house because he doesn't want to give them the virus,” she said.

Pandemic shines a spotlight on racial disparities

The coronavirus pandemic is bringing to light inequities in U.S. health care. Death rates from COVID-19 are higher for Black and Hispanic people than for white people. It’s a pattern familiar to people who work with dementia sufferers.

Black Americans are two to three times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than white people. Hispanics are up to two times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than whites.

“We know that systemic inequities, social determinants of health — where you live, work and play — can make an extreme difference,” said Rosalyn Reese, director of diversity and inclusion at the Colorado Alzheimer’s Association.

Higher rates of diabetes and high blood pressure contribute to the likelihood of developing dementia. Lack of regular access to health care makes it worse.

“Hispanics are also less likely to be insured. And this really keeps our families from seeking a diagnosis, considering that they will have to cover these costs out of pocket,” said Marlene Franco, who works in outreach to the Hispanic community for the Alzheimer’s Association.

“We're also seeing a distrust of the health care system in these communities, and many of these are driven by language and cultural barriers," Franco continued. "You know, not being able to communicate with your doctor in your dominant language, or having a family member serve as an interpreter rather than a trained healthcare professional.”

Where dementia sufferers and caregivers can turn for help

The Alzheimer’s Association of Colorado runs nearly 90 support groups across the state, all of them online for now. Their website lists warning signs to help individuals and their families pursue a diagnosis.

Amelia Schafer, the Association’s executive director, said a diagnosis can be a relief.

“Imagine living with all the symptoms we’ve talked about and yet not having a diagnosis,” she said.

Schafer also encouraged caregivers to consider bringing someone into the house for a few hours, despite COVID-19 worries.

“I think we're all figuring out how to be as safe as possible, but also how to continue to live, because our emotional wellbeing is important as well,” she said. “The depression and anxiety we're seeing, that's something we have to address. There are some ways to do this that can be safe and can be a much better experience for the person, the caregiver and family.”