In April, Dr. Abbey Lara worked her first shift treating pulmonary and critical care patients in the COVID-19 section of the ICU ward at University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora.

She counted 16 patients: two African American patients, one Filipino patient and 13 Latino patients.

“It was incredibly striking,” said Lara, the daughter of migrants from Mexico. She didn’t have a single white patient that week. “That was a personal ‘aha’ moment for me.”

It brought home the impact the disease was having on people of color in Colorado. In her sick patients, Lara saw not just the effects of a virus, but the fallout of longstanding disparities in access to reliable, affordable healthcare.

“This is a conversation that has been happening for decades: How do we provide healthcare for all? Healthcare to me is a right. It's not a privilege,” Lara said. “That's the thing that has been most striking to me is that many of my patients have not had that preventative care.”

Black and Latino residents are getting sick and dying from COVID-19 at higher rates in Colorado, and nationally. They are also disproportionately feeling the effects of the pandemic-sparked recession: 28 percent of Hispanic Coloradans worry they will not be able to afford food for their family, according to a new Colorado Health Foundation survey, and 37 percent of Black Coloradans fear losing their home because they can’t pay the rent or mortgage.

In response, activists have demanded action, and local community health centers and neighborhood groups have launched efforts of their own to fill the gaps. Systemic responses, including statewide efforts robust enough to meet the intense health and economic demands, have lagged behind, although they appear to be gaining momentum more recently.

With the possibility of a second wave of COVID-19 infections looming as Coloradans go back indoors in the fall and winter, health care professionals are wrestling with how to better protect residents in vulnerable populations, starting with Black and Latino residents.

“COVID has had a devastating impact on the Latino community.”

That’s what Veronica Crespin-Palmer has seen. She’s the co-founder and CEO of RISE Colorado, a community group based in Aurora that works with low-income families. People are “having to make really impossible choices, like: ‘Do I go back to work so I can keep a roof over my family's head and put food on the table and leave my children alone because I can't afford childcare?’”

That’s the situation Tati and Fabian, both immigrants from Mexico living in Aurora, are in. The couple, who work with RISE, are in their early 40s, with three sons and a daughter, the oldest who is in high school. She works as a housekeeper, he’s in construction. CPR is using pseudonyms due to their undocumented status and worries about safety.

“Since the virus hit, we’ve been unstable and insecure,” Tati said. “The virus kicked in and my husband lost several jobs.”

All but one of Tati’s cleaning jobs dried up. Now, they’re worried about getting evicted, as their bills accumulate.

“It’s terrible,” Tati said. “Every single cent that comes into our home, we have to cherish it, like it was a treasure.”

They’ve felt pressure from every side: Fabian works with a cousin who came down with COVID-19. The couple never got it, but they worried about it constantly. Fabian has diabetes, thyroid problems and asthma, Tati has high blood pressure, and two of their kids have asthma. They don’t have health insurance, though Medicaid covers the children. On top of that, they’re trying to manage remote learning for four kids at once and worries about safety in their neighborhood.

“My body is going through a lot of stress,” said Tati.

She’s had panic attacks. Tati said families like hers would benefit from more government assistance.

“We work hard, we pay taxes,” she said.

Undocumented immigrants were excluded from all federal coronavirus aid.

Crespin-Palmer said groups like hers have stepped in. They do everything from connecting families with food supplies and mental health support to providing direct cash assistance.

“Many in the Latino community are not receiving the support they need due to their immigration status,” she said. “To me, this is a really important part of the untold story.”

Some of the families live in multi-generational homes where multiple family members caught the virus.

“They're still having to work two or three jobs,” said Jim Garcia, CEO of Clinica Tepeyac, a community health center in Denver’s Globeville neighborhood. “Typically those are in the frontline, higher risk, type of jobs.”

New research found working in the food service sector is a risk factor for Latinos in the US. For Black residents, risk factors include using public transportation at high rates, breathing a lot of air pollution and living in certain facilities, like nursing homes, or being imprisoned at disproportionate rates.

In Colorado, Black residents make up roughly 6.5 percent of deaths and 10 percent of hospitalizations despite being 4 percent of the population. Hispanics are 22 percent of the population, but have a much higher percentage of cases — 38 percent, according to the state’s COVID-19 data. At one point in May, more than half of COVID-19 patients were Hispanic, according to data released by the state health department.

Whites make up almost 68 percent of the state’s population, but just 37 percent of cases, and 41 percent of hospitalizations. (Note: demographic information is unknown for 15 percent of hospitalized patients.)

The state’s picture echoes the national story. In July, data showed Latino and African-American residents had been three times as likely to get infected with the virus and twice as likely to die from it than white Americans.

When Dr. Jandel Allen-Davis, president and CEO of Craig Hospital in Englewood, began hearing about the emerging health disparities, “my somewhat realistic and cynical comment was ‘This surprises you, why?’” she said. “We’ve got to actually focus on the social determinants of health,” the root causes.

Some hope the pandemic, which has now claimed more than 190,000 lives in the US, serves as a tipping point in awareness about the heavy toll of health disparities.

“This time of incredible loss of life can not be for nothing,” Crespin-Palmer said.

At first, Community Health Centers were swamped with patients and had little support

The pandemic caught many local health professionals, public health officials and political leaders by surprise. It took time for decision-makers to realize how heavily Black and Latino residents were impacted. But given the historic realities, doctors and health advocates say that could have been anticipated.

“It was a very slow response. We had a lot of challenges,” said Dr. Pamela Valenza, the chief health officer with Clinica Tepeyac. The community health center serves Denver’s Globeville neighborhood. It was swamped with patients, including staff members, who had COVID-19 symptoms. They needed testing and treatment, but “we didn’t have the testing swabs,” Valenza said.

Instead, they told patients to stay home and isolate or go to the emergency room. She said they needed health guidance in Spanish, and more support for treating patients “who might not feel comfortable going to areas outside their clinic based on immigration status.”

“I think overall there was a general lack of coordination in the response, a general lack of leadership,” Valenza said. That left health centers, and business owners, to figure out how to deal with staff, processes and practices to keep businesses open.

Garcia says they didn’t have enough personal protective equipment. He said support from the state and Denver’s public health department “was on the slow side to start,” but has improved in recent months. He said local foundations also stepped up with substantial philanthropic help.

In the early weeks of the pandemic, communities of color and top national physician groups pushed the Trump administration and states to release more detailed racial data. Colorado’s health department began collecting it in May; now the state has it for the vast majority of COVID-19 patients treated in hospitals.

In mid-April, Gov. Jared Polis established the COVID-19 Health Equity Response Team, headed by the office of Health Equity. Its mission: to ensure racial and ethnicity COVID-19 data are “accessible, transparent and used in decision-making,” determine proactive measures to prevent the virus’ spread and “help curb health disparities” related to it.

“The very first piece to addressing this is shining a light on it,” Gov. Jared Polis said at a mid-August press conference as he unveiled a revamped COVID-19 website, with easier-to-access data on disparities. He said those health gaps “are a result of the long tail of systemic racism.”

Pressed by staff, in July health department director Jill Hunsaker Ryan told the Denver Post the state would declare racism a public health crisis, in response to demonstrations over racial inequities and police brutality and disparities underscored by the pandemic.

In August, Polis issued an executive order to make the state government's workforce of over 30,000 more diverse and inclusive. It outlines measures like hiring procedures and mandatory training on “implicit bias, historical injustices and trauma.”

"This has been a long time in the making, I’m excited to see what comes of it,” said Web Brown, who directs the Office of Health Equity. The executive order asks agencies to adopt new guidelines using existing budgets. That means there's no new money for now, but agencies can request more in future years.

Around COVID-19 testing, "it's a trust issue"

Community health groups stepped into the void that a lack of federal and state planning left, and have taken the lead on planning for potential future waves of infection. Clinica Tepeyac now partners with the state health department to offer a free, drive-up test site at the Globeville Community Church right next door.

“We're doing it by appointment, trying to control the flow of traffic in the neighborhood,” Garcia said. “We want to make it available both to our patients and to the broader community.”

“The big testing sites like at the Pepsi Center, I would say that for communities of color, that may not be the optimum,” he said. Garcia lists language barriers, cultural barriers, “immigration challenges” and transportation as obstacles to getting tested.

“It's a trust issue. I think a person's going to be much more comfortable going to a small community health center like ours,” he said. “They're going to be comfortable sharing information and knowing that we're going to protect that information and protect that relationship that we have with our patients.”

In recent months, the state health department increased testing availability and access, with more than 50 free community testing sites. It created guidelines for a public health response for people with limited English proficiency and provides translations of critical materials on the state’s COVID-19 website in Spanish, as well as Vietnamese, Simplified Chinese, Arabic, Nepali and Somali.

The governor, who speaks Spanish, has a Facebook page in Spanish, social media posts and press releases are translated, and his COVID-19 press conferences are translated into Spanish and posted to the Facebook page.

Members of the state’s health department participated in a 100 percent Spanish town hall with Univision Colorado, Polis, and other state agencies. The agency also hired Spanish-speaking contact tracers and case investigators to provide “culturally competent” disease investigation.

Meantime, Clinica Tepeyac is now seeing about 40 percent of its patients via telehealth, which seems to be working for most.

“We're trying to look at unique ways to serve the needs of the community right now,” Valenza said.

The clinic has also become a critical source of other health services. Staff have given out free blood pressure monitors and glucometers, for diabetics to check their blood sugar, and wellness bags with lavender oil and information about behavioral services. They’ve started drive-up service for patients who have uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes. It’s the kind of preventative care Lara, Allen-Davis and other health professionals emphasize.

“The clinic is a very safe place to be,” Valenza said. “We have a small waiting room, so we're trying to think outside of the box about how we can serve as many patients as we can.”

In North Park Hill, a diverse neighborhood with a large Black population, the Center for African American Health, a community group, is taking a similar approach. On a recent Friday, a steady stream of people lined up in their cars to get the nasal swab and find out if they have the virus.

“I think it's a very good thing,” Aurora retiree Barbara Goree said.

She’d been hospitalized in March with double pneumonia; a test revealed it wasn’t COVID-19. She came to the center to get tested again, out of an abundance of caution. She once again tested negative, giving her peace of mind.

“I’m still cautious,” Goree said. “I think that more people should take advantage of it.”

Deidre Johnson, its CEO and executive director, hopes to see concrete changes.

“I think the system is starting to admit it, but the question is what's being done about it? I think that varies,” said Johnson, who sits on the state’s health equity response team. “Some recommendations are being worked on, but to be honest, the real work that nourishes my heart is action.”

When the pandemic hit, unemployment, evictions and food insecurity all spiked.

“You name the kind of area of life, we are feeling it,” she said.

The center was able to raise and give out $82,000 to families who needed rent and food assistance, prescriptions and emergency money to pay bills.

Johnson said economic opportunities are critical.

“If we don't do things really fundamental to change how our systems work, we'll keep having these disparities. And then the next COVID will wreak the same havoc,” she said.

At Denver Health, a large safety-net hospital that has treated many COVID-19 patients, Dr. Cory Hussain is also thinking about how to get people of color to see doctors more frequently, to try and control pre-existing conditions and maybe avoid the worst of diseases like COVID-19.

“These are conditions that are chronic, and they're managed by a physician who can, first of all, diagnose these and second of all, monitor and treat them,” Hussaid said. “These patients are being admitted to the hospital, have these conditions that are not very well managed due to access to healthcare.”

That access to healthcare has to do with financial stability and insurance. But it also has to do with distrust stemming from decades of mistreatment by the medical establishment. One infamous example is the Tuskegee study, which involved doctors allowing Black men to die of syphilis.

Patients who are people of color tend to go to the hospital when they are severely ill, but not before that, Hussain said.

“It's kind of laid bare for even us physicians the systemic issues we have with systemic racism and access to care,” he said.

For non-English speaking patients, access to care starts before they even enter a hospital or doctor’s office.

“How do you just pick up the phone when you don't speak Spanish or English? How do you get information? How do you make an appointment? How do you get directions to get to a hospital?” said Hussain, who is Pakistani.

At Denver Health, flyers with information about care and how to get to and navigate the hospital are available in multiple languages. But more work has to be done to reach people who are scared to go to the hospital.

“Especially with the current administration and the fear of deportation, I try to explain to them, like you still need to come to the hospital and it's not an unsafe place for you,” Hussain said.

As a person of color, he was not very optimistic at the beginning of the pandemic. Then things started to change.

“Now I am fascinated because all my colleagues who are fighting for racial justice, especially around COVID are all cisgender, white, male and female,” he said. “And they are so committed to changing this conversation and really pushing our organization to go in a different direction to address these shortcomings. It gives me hope.”

Dr. Terri Richardson, with the Colorado Black Health Collaborative, said partnerships with other community groups, health departments and the state’s insurance exchange are emerging. The groups have worked together on webinars, chats and email blasts to provide education and awareness about COVID-19.

One collaboration, with Denver Health, aims to educate the community about vaccines.

“We know we will have some work to do in that space as well, because that’s going to be one of the things that’s going to help,” Richardson said.

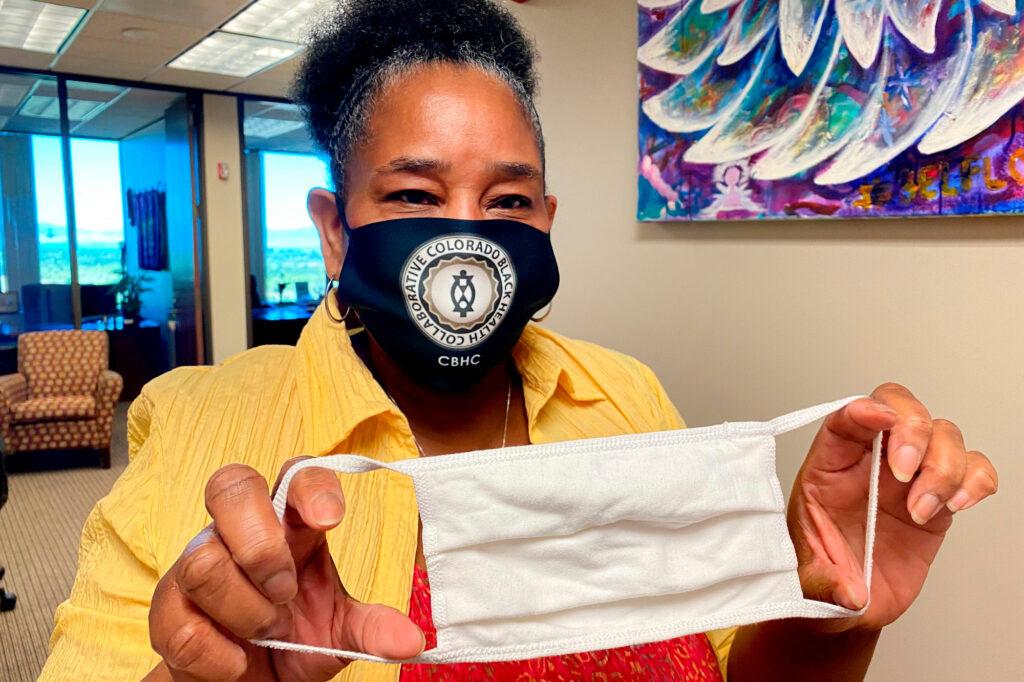

And the group is working to get more masks out into the community — a preventative measure. Inside its Aurora office, project coordinator Tracy Gilford wore a mask with the group’s logo on it. She pulled out a plastic-wrapped package with white cloth face masks, five in each pack. Donors paid for them.

“It’s amazing the number of people that you see running about that don’t have a mask on,” she said. “But when you give it to them, how appreciative they are, especially those Black mothers that I’ve seen out there with children that don’t have masks.”

She said since early July they’ve passed out 600 packs or 3,000 masks, including at churches. One volunteer has given out 400 as she travels around town via the city bus. Now, they’re just awaiting a new shipment.

CPR's Claire Cleveland contributed reporting to this story.

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Dr. Pamela Valenza's surname.