Updated 12:31 p.m.

Colorado Republicans will soon have a new leader at the helm as they try to chart a path forward following several years of steep election losses.

The five candidates vying to head the state’s Republican Party are making their final pitches before the election on March 27, 2021. And as one candidate bluntly put it when asked about the party's losses, “we are in a horrible, bad, no good, very lousy place.”

The outgoing chair, Rep. Ken Buck, decided not to seek reelection to the two-year position, opening the door to a diverse slate of contenders. While just a few hundred party activists will select the next chair, their choice will have ramifications for how Republicans make their case to the broader electorate as they try to reverse some of the gains Democrats have made.

“They are the person that is quoted on a regular basis,” said Republican political consultant Tyler Sandberg. “They are the face of the Republican Party when there's not a legislative debate happening, or candidates that have been nominated. They speak for the party to the unaffiliated voter, to the average consumer of news.”

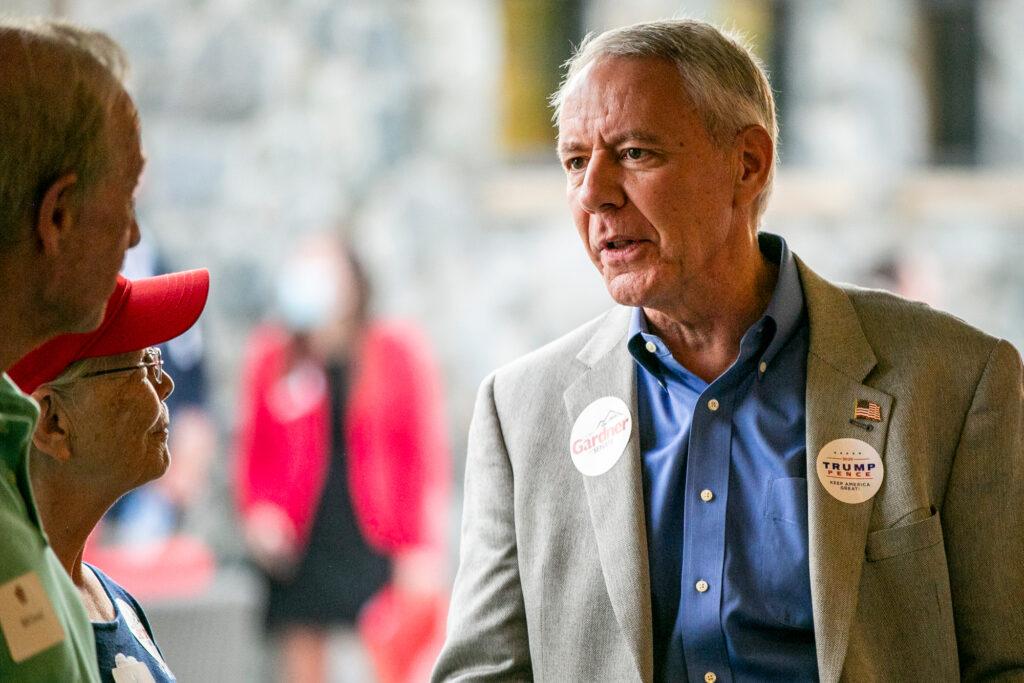

The frontrunners in the race are former Secretary of State Scott Gessler and current party vice-chair Kristi Burton Brown, who first rose to conservative fame as the author of Colorado’s failed 2008 personhood amendment. The field also includes former congressional candidates Casper Stockham and Rich Mancuso and political consultant Jonathan Lockwood.

The field is diverse both ideologically and demographically. Stockham is African American. Lockwood is gay, and strongly opposed the reelection of President Donald Trump, to the point that he voted for the Biden-Harris ticket.

A focus on party growth, and election doubt

The candidates made their cases at a recent forum hosted by the Colorado Hispanic Republicans.

“No one like me has been elected to lead the Colorado Republican Party,” said Burton Brown. “Since before I was born, suburban moms like me, who are lawyers, who have children, are Democrats in Colorado.”

“If we do not win unaffiliated voters, members of our minority communities, suburban moms and millennials like me, if we do not win new kinds of voters and bring them into our party, we will not win in Colorado,” she said.

To do that, Burton Brown argued the GOP needs to focus on ‘micro-targeting’ and local issues. “This is what happened in the Georgia Senate race. The Democrats ran on local issues that the swing voters cared about. The Republicans campaigned on national issues, which are absolutely important, but not what the swing voters often care about.”

Gessler agreed that the party should be grounded in bread-and butter-issues, to “be relevant to people's lives.”

“We need to talk about conservative solutions to people's problems. We need to hold Democrats accountable for the massive unemployment we face in the state, the loss of children's education... the attack on our industries and jobs.”

Yet as much as the candidates have said the party should focus on everyday concerns, the race itself hasn’t been divorced from national politics. In an echo of national Republicans, most of the candidates say election integrity — specifically overhauling some of Colorado’s voting laws — is a big priority.

For Gessler, who served as the state’s top election official during the time Colorado moved to all-mail ballots, this topic requires a bit of a balancing act.

At a state legislative hearing on Colorado’s election security last December, he defended Dominion Voting Systems, the Denver-based company that Trump and his allies on the right have accused without evidence of switching votes to Biden. Dominion, one of its employees, and another company, Smartmatic, have since filed numerous defamation lawsuits, saying their reputations have been destroyed.

Dominion technology “generally performed very well in Colorado,” Gessler told the legislative panel. However, in his run for chair, Gessler has called the results of the presidential race into doubt and emphasized his work with the Trump campaign to challenge the vote in Nevada.

“There are real concerns about this election and I understand those completely,” Gessler told CPR News. “I do think we need to get to the bottom of some of these questions.”

Lockwood said he feels like Gessler in particular has been “all over the place” when it comes to election fraud. For his part, Lockwood would like Republicans to move on from the 2020 election but acknowledged that’s not easy.

“It is probably leaps and bounds above all other issues, the number one issue to a lot of the people voting in this chair race,” he said. Lockwood’s message to those Republicans? “Joe Biden won the election. It's time to move forward. And when mainstream voters hear the words, ‘election integrity’ from a Republican's mouth, they hear ‘election denial.’ And that is not a good thing for the party.”

Lockwood describes himself as an unconventional disruptor and an innovator. He believes the next chair needs to connect to all of the suffering people have faced during the pandemic and have ideas on how Colorado can rebuild.

“We also need to spread the good news and tell people it's not all doom and gloom. You can be self-determined, you can succeed. You need to start planning for success, not for failure.”

Mancuso noted the next chair will have the difficult task of reaching out to the different factions within the GOP: those that want to move on from the Trump era, and those who think the establishment never backed him enough.

“We lost a lot, a few years ago, (of) the ‘never Trumpers,’’ he said. “Now we're losing the ‘forever Trumpers.’” He said the party needs to create more opportunities for people to listen and share their perspectives. “I wrestled in school. I boxed golden gloves, and it's going face-to-face, nose-to-nose. It's explaining to them where we're coming from, to bring them back in.”

For Stockham, growing the party means taking action now. After the 2020 election, he formed the group America First Republicans, with the goal of training grassroots candidates, particularly young people of color.

“What I've been asking (the Party) to do for eight years is to show up in the communities more, the Black and Hispanic community. They've been ignoring those communities, thinking that they didn't need the vote,” Stockham said. “But now it's evident that in order to win statewide, we have to have that vote. It's not a question of, ‘it'd be nice to have.’”

The gender, age and racial diversity of this group of candidates stands out when compared to the makeup of Colorado’s elected Republican officials. At the Colorado capitol, the GOP caucuses are overwhelmingly male and white, with just one Republican woman serving on the Senate side, and no members who are openly gay.

Both of the candidates vying for the party’s vice-chair position are women of color.

Republicans see opportunities, in spite of headwinds

Colorado has traditionally been a purple swing state, but in the last few cycles, it’s looked increasingly blue. Democrats now control the legislature, all major statewide offices and both U.S. Senate seats. However, former Republican Congressman Scott McInnis told CPR News he thinks Colorado may just be naturally due for a pendulum swing toward the GOP if the party can capitalize on opposition to Democratic policies.

“The Democrats in Colorado are overreaching,” he said. “So I think there's going to be some momentum for a change in the future if you keep going the direction on some of the extreme positions they've taken.”

The last time Republicans wielded significant power at the ballot box was 2014 when they took control of the state Senate. That same year the GOP flipped a U.S. Senate seat from blue to red and won the races for Attorney General, Secretary of State and Treasurer. The previous year Republicans recalled two Democratic state lawmakers after the legislature passed several gun control measures.

Yet, nearly a decade later Colorado’s demographics have changed significantly. Unaffiliated voters now make up the largest percentage of the electorate. Over the past five years, the state’s Democratic Party has surpassed the GOP in registration, adding 222,018 active voters, while Republicans only grew by 70,336. More recently, in the week after the U.S. Capitol insurrection, nearly 5,000 Colorado Republicans left the party.

Faced with those numbers, all of the candidates for GOP chair talked about the need to raise more money, improve communication with local officials and be more innovative.

“We're the incredible shrinking party,” Gessler said. “We focus on a few candidates, usually federal candidates, and leave everyone else to try and swim on their own. I would say the party raised $285,000 for state funds the entire two-year cycle. That's almost nothing. Our communications strategy is not relevant. It is not inspirational. It's oftentimes not even heard.”