Colorado’s Independent Redistricting Commission agreed on a congressional map at its final meeting Tuesday, just minutes before a midnight deadline. It will now go to the Colorado Supreme Court for approval.

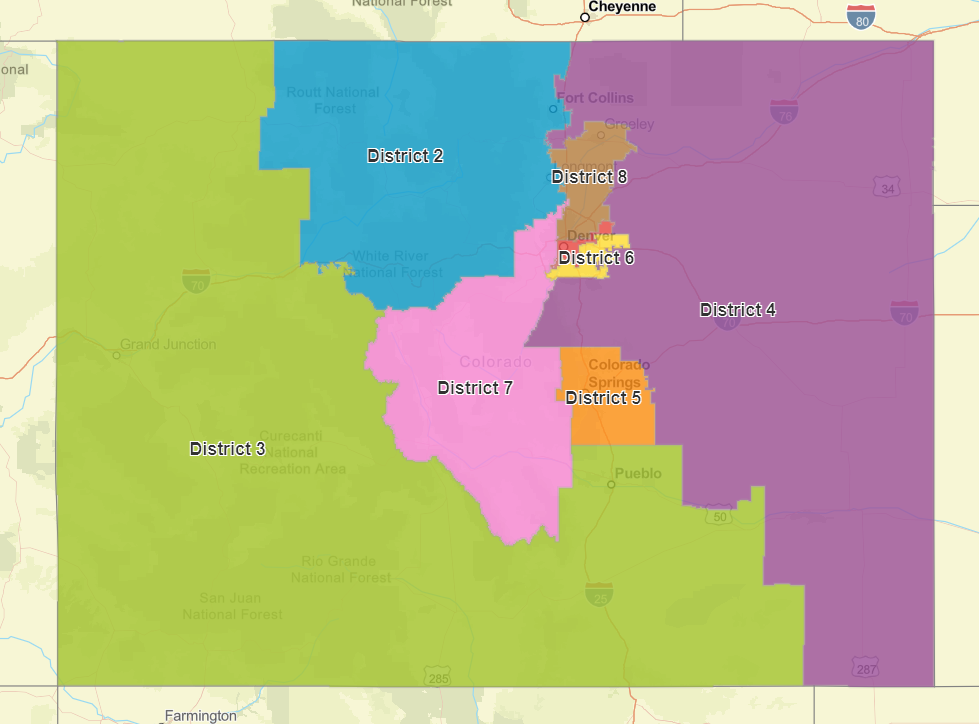

The new map is largely modeled after Colorado’s current congressional boundaries, while making room for the state’s new 8th congressional district which will sit along the I-25 corridor north of Denver.

Politically, the map creates four Democratic seats, three Republican ones and a swing district — the new eighth — that leans slightly to the left. The boundaries give all of Colorado’s current members of Congress a strong chance of holding on to their seats.

This final map was a Democratic amendment to a plan drawn by nonpartisan staff based on public feedback. In the end, it was supported by eleven of the panel’s twelve commissioners, with just Democrat Simon Tafoya voting against it.

“We have made history here in the state,” said Republican commissioner Danny Moore.

A struggle for agreement

Commissioners waded through six rounds of voting and hours of increasingly testy debate Tuesday night before reaching their final result.

For much of the meeting, commissioners were split between the map they finally chose, and other versions that made greater changes to the political lines.

“This process is a little crazy,” said Democratic commissioner Martha Coleman, after the fifth round of voting resulted in a three-way tie between maps. “I think if we really think about this clearly, we all have the desire to vote a map in.”

At times the debate became heated, as commissioners argued about whether boundary lines did the best possible job of respecting different communities, whether to prioritize making one or more districts competitive, and how many Republican and Democratic seats would fairly represent the political makeup of the state.

“I cannot move forward a map that has not one single competitive district,” said unaffiliated commissioner Lori Schell. “I cannot move forward with a map that favors one party over another by two districts. I don't care which party it is. I cannot move forward with that. Given all of this testimony we heard about competitiveness.”

At one point two commissioners said they thought the panel had hit an impasse, But unaffiliated commissioner JulieMarie Shepherd Macklin urged her colleagues to keep voting to try to reach an agreement and fulfill what the commission was designed to do.

“I’m not ready to walk away from this yet,” she told them.

What the new map looks like

The commission’s map still needs final approval from the state’s highest court, and could be challenged by groups arguing the commission failed to meet the criteria required by the state constitution. If the court does not approve this map, the commission would reconvene and hold a public hearing to try to address the Justices’ concerns.

As it stands though, here’s a break down of the eight districts:

CO-1 — Denver makes up this entire district. Because the commission is charged with prioritizing political subdivisions and communities of interest, it was never likely to change much. It’s also the state’s bluest district, with Democratic candidates enjoying, on average, a 57-point advantage over Republicans.

CO-2 — This mountain-heavy, Boulder-anchored district is the state’s second-most Democratic, with a 34-point spread in their favor. It includes Longmont and Fort Collins and then stretches west to Routt County and south to cover the I-70 corridor from Idaho Springs to Gypsum.

CO-3 — This district emerged as the great battleground of the redistricting process, with some commissioners pushing the idea of reimagining it across the southern half of the state. In the final map, it retains much of its current shape; losing some mountain territory while gaining Las Animas and Otero counties in the southeast. The district would likely stay represented by a Republican — the party enjoys an average nine-point election advantage.

CO-4 — This massive Eastern Plains district picks up the eastern side of El Paso County and the city of Loveland in Larimer County, but loses Greeley as well as communities along I-25 and U.S. Highway 87 to the new 8th district and two rural counties to the 3rd district. The district would be the reddest in the state.

CO-5 — In 2010, Colorado Springs was still small enough that the district based in the city included four mountain counties. But the new map shows how much the city and its suburbs have grown. The metro area that stretches from Monument to Fountain is now big enough to become its own district, shedding not just mountain communities but also the eastern third of El Paso County. The conservative city gives Republicans a twenty point advantage.

CO-6 — This suburban Denver district would cover all of the city of Aurora and the south metro cities in Arapahoe County, while losing northern portions to the new 8th district. It would be strongly blue, with a 15-point Democratic advantage.

CO-7 — This district will see one of the biggest border shifts, going from being entirely based in Denver’s northwestern suburbs to covering all of Jefferson County, as well as a wide swath of central mountain counties. While Rep. Ed Perlmutter won his last election by 21 points, Democrats see their advantage in the district narrow significantly, to just a seven-point tilt.

CO-8 — The state’s newest district stretches along the high-growth corridors of the northern Front Range. It is by far the most competitive seat in the state, with Commerce City and other heavily Democratic northern suburbs balanced out by conservative Greeley and nearby communities in the north.

Drawing maps in public, in a break from the past

Tuesday’s decision caps off the state’s grand new political experiment to have a public commission, not state lawmakers, redraw the Congressional and statehouse boundaries.

The statehouse maps are being approved by a separate independent commission and won't be final for a few more weeks.

In the course of its work, the commission held more than forty public meetings around the state and received thousands of public comments.

"When you think of, like, smokey caucuses, those are gone,” said unaffiliated commissioner Jolie Brawner. “We had those open meetings and I just really loved being part of the process.".

Brawner moved to Colorado from Florida in the last decade and said she learned even more about the state traveling to meetings and hearing from residents.

“I feel like I'm part of that huge group of people (who relocated to Colorado and) gave us an eighth district,” she said in the final meeting. “And I love that I am part of the process for drawing that eighth district.”

Over their months of deliberations, the commission weighed how best to represent rural parts of Colorado, and how to ensure representation for different racial and ethnic communities. Latino groups lobbied heavily for district lines that would give their community a strong political voice.

The commission’s final map envisions three districts where white residents make up less than 60 percent of the population: the 1st, 6th and 8th. The new CO-8 would be the most heavily Hispanic, at 38.5 percent.

The commission also spent significant time discussing whether to majorly redraw the state’s boundaries to create a congressional district stretching across southern Colorado.

Simon Tafoya, a Democratic commissioner who comes from Pueblo, was the lone no vote on the approved map, arguing it didn’t do enough to help people of color who live in Southern Colorado.

“I still think there was a better solution and ultimately that’s why I voted no,” he said in his closing remarks. But he added, “it doesn’t take away from the work we’ve done.”

Colorado’s redistricting process got off to a rocky start; the U.S Census Bureau ran well behind schedule to release the granular population data needed to fine tune district lines. That led to a condensed timeline for the commission to develop and agree on a final map.

But even during the closing moments of what is most likely their final meeting, commissioners from across the political spectrum praised their deliberative process and thanked the non-partisan staff for the countless hours of work. Many said they’d do it all over again.

“Together we have changed the course of congressional redistricting in Colorado, and provided an example for the rest of the country,” said Commissioner Schell.

- After 10 Years Of Rapid Population Growth, Colorado Got Another Seat In Congress. This Is How That District Was Drawn

- Redistricting Was Supposed To Be Less Partisan In Colorado. Politics Are Getting In The Way Of That

- After 10 Years Of Urban Growth, Mountain Counties Like Chaffee And Fremont Want A Rural Voice At Congress