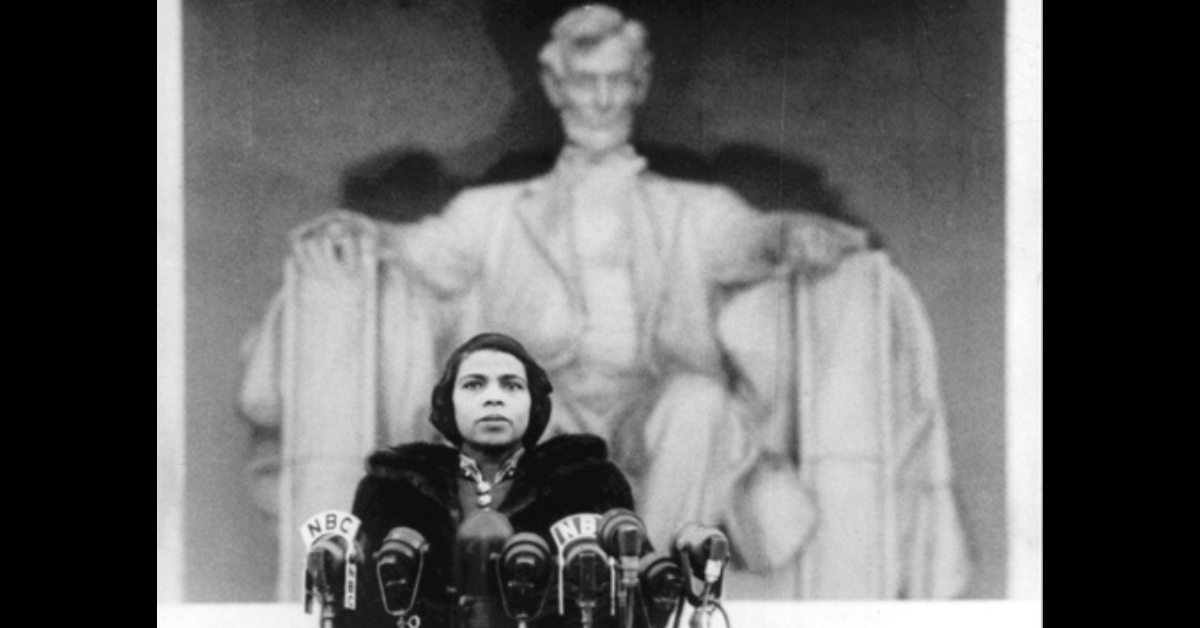

Many of us know the general story of Marian Anderson’s famous concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1939. The Daughters of the American Revolution denied her the ability to sing inside Constitution Hall because she was Black. But many may not know the significance of the final song she sang, the spiritual “My Soul’s Been Anchored In The Lord.” To grasp that significance, it’s important to understand how Negro Spirituals “evolved.”

The songs of the enslaved community are rooted in oral tradition so it’s not surprising there are different melodies, different lyrics, and different intentions to many versions, reflective of the various needs or circumstances of the community. A song may be created by an individual commenting on events, emotions, or thoughts in that moment. Anyone present may add to that song. As slaves moved from plantation to plantation, the songs could change, based on the memory of the singer or the needs of the current circumstance.

“My Soul’s Been Anchored In The Lord” was included in John W. Work’s edited collection (originally compiled in 1940), “American Negro Songs and Spirituals.”

This version of the song focuses on the singer’s commitment to Christian life. Here the singer asserts “My soul’s been anchored in the Lord,” meaning I’ve made a commitment to the Lord, and I will not stray from it. Hence, the anchor, so that the individual is planted, rooted, steady, and unmoving.

The first verse find’s the singer’s Christian faith questioned by a member of the community:

Where’ve you been, poor sinner?

O where’ve you been so long?

Been working out of the sight of man.

The community member insinuates that the singer has not been steadfast in the Christian walk and has strayed, has sinned, perhaps going where an upright person should not go. The singer insists that he/she is living right and working hard, simply not within the visual purview of the community member.

The second verse finds the singer testifying and signifying:

You may talk about me just as much as you please,

You may spread my name abroad;

I’ll pray for you when I get on my knees.

The singer accuses the community member of gossiping and spreading rumors. The retort to this slander is meant to be both literal and sarcastic. It is an indictment on the supposed character of the community member, accusing that person of less than Christian behavior by gossiping.

Now let’s consider the version arranged by African-American classical composer Florence Price for Marian Anderson’s Lincoln Memorial concert in 1939.

Anderson chose “My Soul’s Been Anchored In the Lord” to close the concert. It was a bold move.

Not only did performing a Negro Spiritual at a classical music recital elevate the music of slaves, according to ethnomusicologist Alisha Lola Jones in an article for NPR, Anderson also gave it a place of prominence at the end. The song of her ancestors was the final word in a symbolic retort to the snub by the Daughters of the American Revolution. Jones refers to this as “signifying,” an African American rhetorical device wherein Blacks communicate their true intentions veiled in hidden meaning. Additionally, Jones points out the acknowledgment of Florence B. Price’s full name on the printed program (the other composers merely had their first initial and last name on the program), highlighting Price’s gender in a space typically occupied by men. Anderson not only elevated a woman in this male-dominated arena, she also honored an African American woman.

In de Lord, in de Lord,

My soul’s been anchored in de Lord.

In the case of the Price arrangement, we see solidarity and trust among Black women. We also see commitment and trust in God, where others may prove unreliable and untrustworthy. When those who make promises and break them disappoint you, be sure to place your trust in a dependable source and drop your anchor there.

M. Roger Holland, II is Teaching Assistant Professor of African American Music and Theology at the University of Denver’s Lamont School of Music, and Director of DU’s Spirituals Project Choir.

Listen to Professor Holland’s monthly musical selections and commentary throughout the year on CPR Classical, including Sunday mornings on our choral music show Sing!, hosted by David Ginder.

- February's Spiritual - “Lord, How Come Me Here?”

- March's Spiritual - “He Never Said A Mumblin Word”

- April's Spiritual - "Ride On, King Jesus"

- May's Spiritual - "Every Time I Feel The Spirit"

- June's Spiritual - “That Great Gettin’ Up Morning”

- July's Spiritual - "God Is A God"

- August's Spiritual - “Way Over In Beulah Land”

Hear CPR Classical by clicking “Listen Live” at the top on this website. You can also hear CPR Classical at 88.1 FM in Denver, at radio signals around Colorado, or ask your smart speaker to “Play CPR Classical.”