Wondering what to get that special someone in your life you hate the most when they die?

Maybe this story will help:

Gerald Phipps owned the Denver Broncos from 1961 to 1981. Most of those years, the Broncos weren’t very good, until the late 1970’s when “Broncomania” took off and the Broncos, led by their ferocious Orange Crush defense, finally started to win some games against their archnemesis, the Oakland Raiders.

The man behind the Silver and Black, Al Davis, owned the Raiders beginning in 1972. The Raiders were one of the most dominating teams in the NFL during that era.

The Broncos and Raiders would become one of the fiercest rivalries in football.

And the two owners, Phipps and Davis, didn’t like each other at all.

“Al Davis sent black and silver roses to my grandmother's funeral,” said Vickie Owens, Phipps’ granddaughter.

Wait, what?

“Oh, (Davis) and my grandfather hated each other — I mean hated each other,” she emphasized. “Oh God, yes.”

So yeah, the Broncos and Raiders rivalry has been intense for decades. And for a long time, Al Davis was at the center of the feud.

This month marks the 10-year anniversary of Davis’ death. The man won a lot of games, and made some blue-and-orange-colored enemies along the way.

And boy howdy, did Davis and his “Just win, baby,” motto get under the skin of Broncos players.

“There was something about the Raiders and the ‘Just win, baby’ phraseology, ‘Just win, baby, and you can do whatever you want.’ And they did,” said Broncos Ring of Fame linebacker Tom Jackson. “They were an outstanding team, outstanding. But they were out to let you know it. And their arrogance would fit better in this age and time than it did back then.”

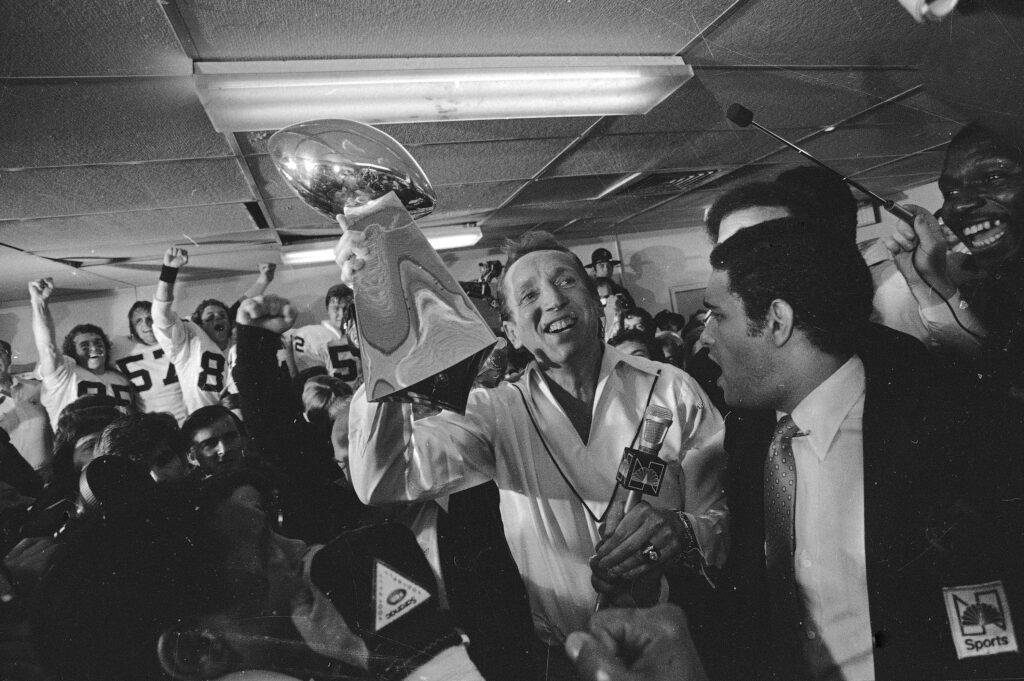

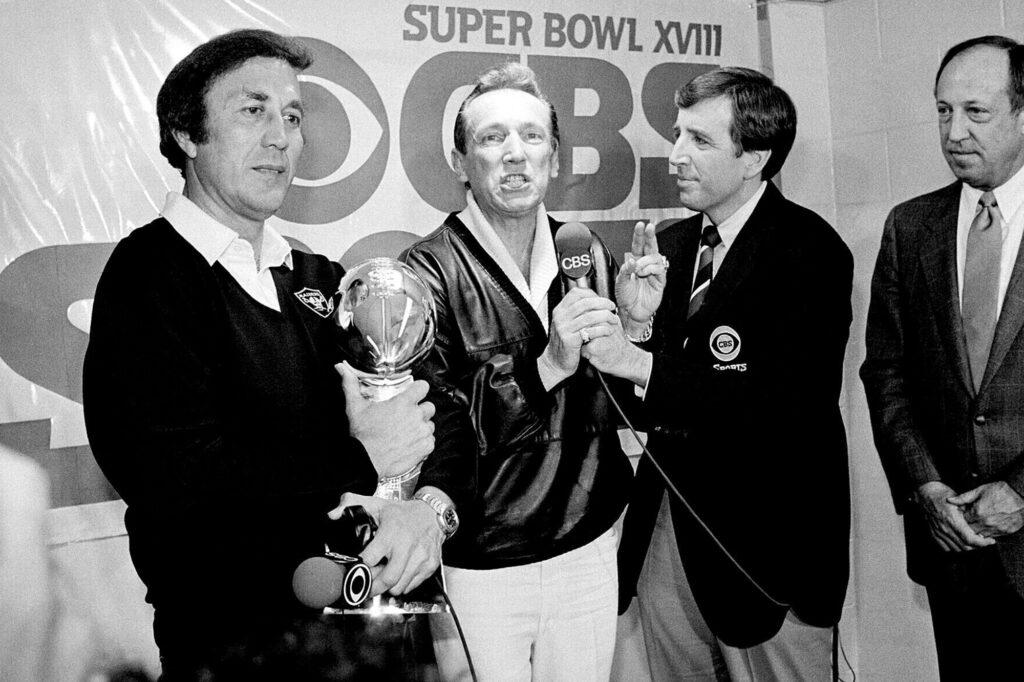

Jackson was part of the Broncos tremendous Orange Crush defense of the 1970s and 80s, a time when Al Davis’s Raiders dominated football. Between 1967 and 1985, the Raiders won 12 AFC West titles and three Super Bowls — all while Davis served as the team’s owner or part owner.

It wasn’t just Davis’ Raiders winning a lot of games that bothered opponents — it’s how they won, and how they behaved as an organization.

There’s an old poem titled “Pirate Wind '' that was rewritten by NFL Films President Steve Sabol, “The Autumn Wind,'' that became the battle hymn of Raider Nation.

That was Al Davis’ Raiders.

“Al Davis is this guy on the sidelines dressed in black and kind of a snidely, whiplash character of football and they beat you all the time — I mean they beat you all the time,” said Jim Saccomano, who led the Broncos public relations department for more than 30 years. “And they had these characters who were tough guys, like the name, fitting of the name Raiders: pirates. Take no quarter, give no quarter.”

Under Davis, the Raiders had a notorious bad boy image. While many NFL owners might think twice about hiring players with bad reputations, Davis was the opposite. His rosters were often filled with malcontents.

“This was an organization owned by a man, Al Davis, who gave people second chances, and in many cases third chances, fourth chances, and in many cases more chances than others thought players should be given,'' said former Raiders CEO Amy Trask. “He would give chances to those who other organizations had labeled behavior problems or worse.

“And that struck a chord with me. In kindergarten I was labeled a behavior problem and that label stuck with me through high school. And most people who know me know the label is still appropriate.”

Davis was one of the most controversial owners in the NFL. One one hand, he was a champion for civil rights and created one of the most loyal fan bases in all of sports. On the other hand, he was often involved in legal battles with the league and sometimes clashed with his own star players.

“I would say there are examples politically, and you can figure it out yourself,” Saccamono said of Davis’ tell-it-like-it-is attitude. “Some people just go along and they’re gonna be polite, but some people say, ‘No, no, I’m gonna do this and you can't stop me. I’m just gonna do it, that’s all.’”

Roots of a rivalry

During the 39 years Davis owned the Raiders, his team and the Broncos were involved in many high-stakes battles. But the 1977-1978 season is when the rivalry really took off. The Raiders were defending Super Bowl champions while the Broncos were in the playoffs for the first time ever. The two teams met in Denver for the AFC Championship on New Year’s Day 1978.

The Broncos won that game and went on to play in their first Super Bowl, which they lost to the Dallas Cowboys. But Al Davis didn’t handle losing to the Broncos well. And in the offseason, he lobbied for a new NFL rule that would forever change the way the game is played.

“The rule (at the time) was you could bump receivers all over the field until the ball was in the air,” said Jackson, who played in that 1978 AFC title game. “Our coach told us no one will ever be open. No one’s ever gonna be open. Because if you let us hit everybody on the field until the ball’s in the air, what we're gonna become expert at is disrupting every route.

Broncos defenders’ manhandled Raiders receivers that game, taking away Oakland’s top weapon — speed. But in the offseason, Davis fought for a rule change that benefits offensive players. And that led to the so-called “chuck rule” that’s still in effect today, which prohibits defenders from making contact with receivers beyond five yards of the line of scrimmage.

That season was the start of Broncomania. And for the first time ever, the Broncos felt like they were on equal footing with their archrival.

“(Former Broncos coach) John Ralston had told us during his tenure as head coach that if you wanna go to the Super Bowl you're gonna need to beat the Oakland Raiders,” Jackson said. “He was very blunt about it. That turned out to be true. And that win, I won't say it put us on the map, but it was a monumental leap.”

From that point on, the Broncos and Raiders would embark on many back and forth battles for AFC West supremacy. Between 1977 and 2005, both teams won two Super Bowls, while the Broncos have had the upper hand in winning more division titles and having more playoff appearances.

“There were many elements that created a very personal animosity between the teams,” Jackson said. “And of course a rivalry isn't a rivalry until both teams have success. And when we finally started to have success against them those feelings started to intensify.

Show Mike the money

Now, every coach will tell the media that it’s just another game when they’re about to take on their rival. But that’s just not true with these teams.

“Absolutely not,” said former Broncos wide receiver Rod Smith with a hearty laugh. “It was nowhere close to another week.”

Smith was involved in a lot of heated clashes with the Raiders during his 14-year Ring of Fame career with the Broncos, but he’ll never forget his first time experiencing the rivalry. Smith was drafted in 1994, the final year the Raiders played in Los Angeles.

“It really was like a movie,” Smith said of the sea of silver and black inside the Los Angeles Coliseum. “Everyone’s wearing black and is carrying anything you can think of in terms of hanging Broncos, or anything that was orange or blue. There were axes with some blood on it. It was cool to see how they loved their team and how they hated our team.

“That was my first experience with the team. And then coach (Mike) Shanahan comes in the next year and that put a whole new spin on it.”

Indeed it did. Shanahan was a former Broncos assistant coach when he left Denver to become the Raiders head coach in 1988. But Davis and Shanahan clashed from the get-go. And, just four games into his second season in Los Angeles, Shanahan returned to Denver as the Broncos quarterbacks coach in 1989. That’s when he and Davis became involved in a public spat over money.

Shanahan claimed that Davis owed him $250,000 in severance pay and that Davis told him he would not pay Shanahan if he took a job with the Broncos. The matter was taken up through NFL arbitration and the league ruled in Shanahan’s favor. But Davis refused to pay his former coach, claiming that the Raiders loaned Shanahan money when he was hired and considered that an offset.

“The money actually carried weight because I’m like, ‘Dude, $250,000? I’d hurt Al Davis myself for $250,000,’” Smith said. “And Mike would just smile about it with a little Cheshire Cat smile Mike had and he would be like, ‘I’m gonna keep burying them in football games before I get my money back.’ And I would say to Al Davis in the press, ‘If you give the guy his money, we’ll stop beating you guys.’”

Sometimes Smith would have a little too much fun reminding Davis about the money.

“We had this little warmup that we do (before games),” he said. “It just so happens one of the footballs almost hit Al Davis. I'm not gonna say any more than that. I'm not gonna say who threw it. All I know is every time we played, and he was in the area, the football almost hit him. And you would see him jump every time, like, ‘Dude you haven't figured this out yet? The football literally is coming at you every time you play here.’”

Trask stands by the Raiders assertion that the loan given to Shanahan was considered an offset to the severance pay, saying, “It’s a much, much longer, in-depth story than the sound bite most people use to say.”

A rivalry renewed each year

It just seems like every time the Broncos and Raiders meet a fight breaks out, sometimes even before the game starts.

“You come down the same tunnel at the L.A. Coliseum,” Jackson recalls. “There were a couple of times when we almost came to blows just because you’re leaving the locker room at the same time and you're coming down the same tunnel.”

Sometimes it’s a physical fight. Sometimes it’s a snowball fight.

On Nov. 22, 1999, several fans at the Broncos stadium (which was called Invesco Field at Mile High at the time) were arrested for throwing snowballs — some of which were packed with batteries — at Raiders players. Raiders offensive lineman Lincoln Kennedy, who was hit in the face with a snowball, went into the stands to confront Broncos fans.

“I'm right behind Lincoln and I'm like, ‘Oh I better go in and help Lincoln!’ Like I’m going to help Lincoln Kennedy at my size, all 5 foot 3 of me,” recalled Trask. “But he was heading into the stands and he was my teammate and I went right into those stands with Lincoln while the Broncos fans were throwing snowballs at us. And I remember a bunch of our players yelling, ‘We gotta get Amy out of there!’ But I was there to protect Lincoln from those Broncos fans.”

Raiders fans sometimes behave badly too.

“They would hurt people, like people in the stands,” Smith said of Raiders fans whenever the team would travel to Oakland or L.A. “I saw people get beat up wearing Broncos stuff and we’d be winning and the next thing we know that dude’s bloodied. And you're like, ‘Damn dude, leave! Wear neutral colors, wear green or something. Don’t wear orange and blue or you're not gonna make it out of here. If we win you're definitely gonna beat up and if you lose you're gonna get beat up, so why in the hell would you wear … ? And you would see some Broncos fans say, ‘The hell with it, I'm going there, prepared to fight or whatever dude.’ It was nuts!”

Davis’ legacy an exercise in the complicated

So, Al Davis’ teams certainly brought out many strong feelings from Broncos players and Broncos fans over the nearly four decades he owned the Raiders.

But looking back at Davis’ legacy, It's also important to note that Davis was a trailblazer in many areas. He was a fierce defender of racial justice. In the 1960’s Davis refused to play in any city where Black and white players had to stay in separate hotels.

Davis hired the first Latino head coach in NFL history, Tom Flores, and the league’s first Black head coach in Art Shell. Both are now in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He also hired Amy Trask, who was the first woman to ever run an NFL team.

“He hired without regard to race, gender or any other individuality, which absolutely has no bearing on whether or not you cannot do a job,” Trask said. “You can love the Raiders and you could have loved Al or you can hate the Raiders and you could’ve hated Al. But if we're all being intellectually honest, we will acknowledge together that he did something decades and decades before others thought to do it.”

Even Broncos players who hated Al Davis on the field admit that the late Raiders owner was one of the most socially progressive owners in NFL history. When Davis died on Oct. 8, 2011, Rod Smith wrote a tribute to Davis for the Raiders website.

“Al Davis was instrumental in hiring some of the first Black players, the first Black head coach in the NFL was under Al Davis, so I gave him kudos,” Smith said. “He had a hand in building the league the way it is today. For me it was an honor that he did what he did. I just give him that much credit and my respect.”

For Trask, talking about Al Davis still brings a wave of emotion — even on the anniversary of his death 10 years ago.

“Well when you just said those words I got covered with goosebumps, or chills that washed over me. And I actually have a little bit of a lump in my throat right now,” Trask said.

“Here’s a man in the early 1980s — and a lot of your listeners weren't even born then. And I share that to focus people on how long ago that was — took a chance and hired a girl. And yeah, I was a girl then. I was in my very early 20s. He never ever cared about my gender, he cared only that I could do a job. And the significance of him doing that at a time when others weren’t doing that could not be overstated.”

And even when Davis would rub people the wrong way, he was still charming in his own way. When Tom Jackson retired from football, he took a job covering the NFL for ESPN. One of his first assignments was to cover Raiders training camp. But when he and his crew showed up to do their job, Al Davis wouldn’t let them in.

“And Al says, ‘Tom, I know you're disappointed, but I'm not comfortable with you covering the Raiders after how personal it was when you played (for Denver),” Jackson recalled.

When Jackson told Davis that he posed no threat because he would be fired from ESPN if he told the Broncos what he witnessed at Raiders camp, “Al looked at me and goes, ‘Tom, let me put it this way. If you were a Raider and you retired from football and went to work for ESPN, and you go to the Broncos practice, I'd expect you to come back and tell me everything they did.’”

“And I said, ‘Now there’s a man that’s brutally honest,’” Jackson said with laughter. “He’s just brutally honest.”