This story is a part of Understanding Southern Colorado's Groundwater, an occasional series from KRCC about groundwater resources. Read more stories here.

As more people move to parts of Southern Colorado, there’s growing concern among some farmers, residents and others about the demand placed on the region’s aquifers. Those are the groundwater resources found near the earth’s surface or even deeper in fractured bedrock.

KRCC’s Shanna Lewis spoke with hydrogeologists Lesley Sebol and Matt Sares with the Colorado Geological Survey to learn more about the aquifers in this region.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Ogallala Aquifer, also known as the High Plains Aquifer

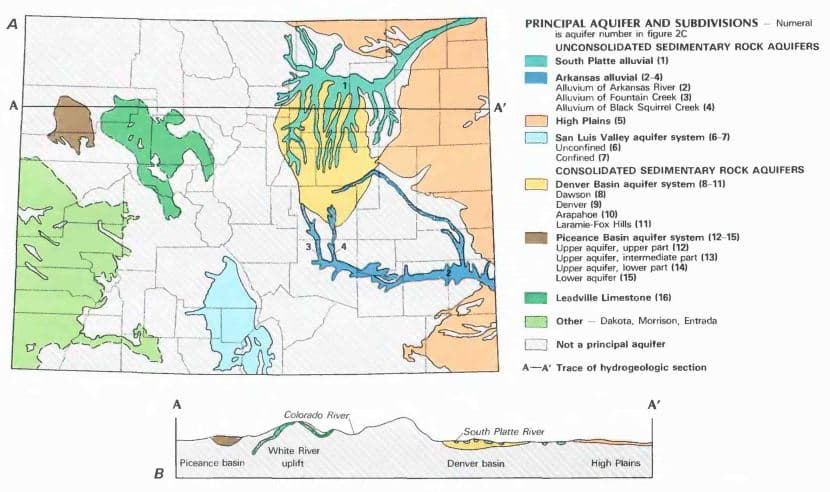

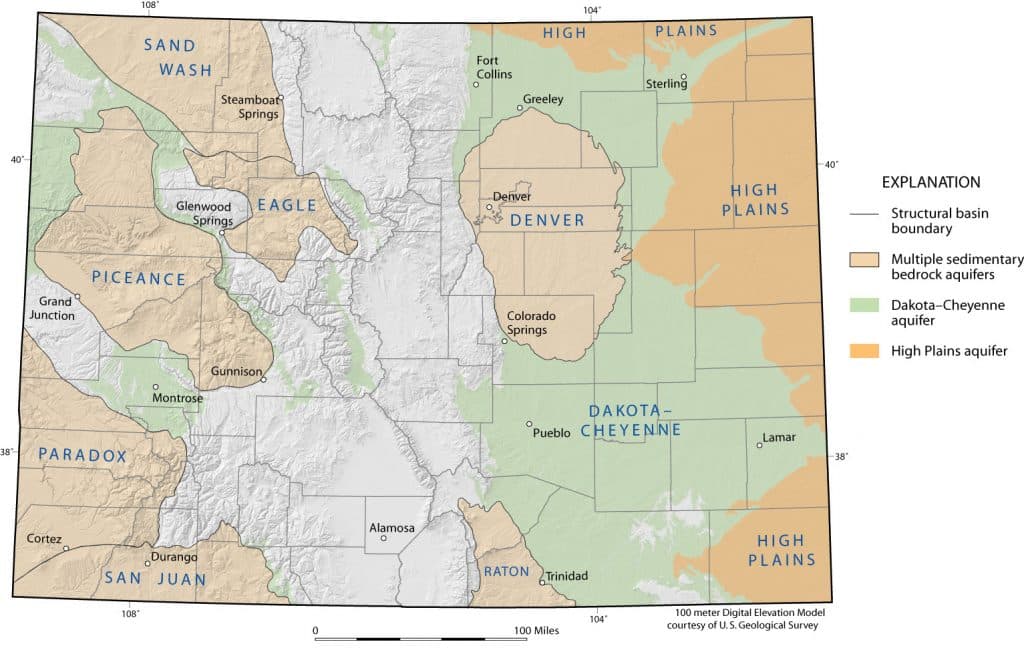

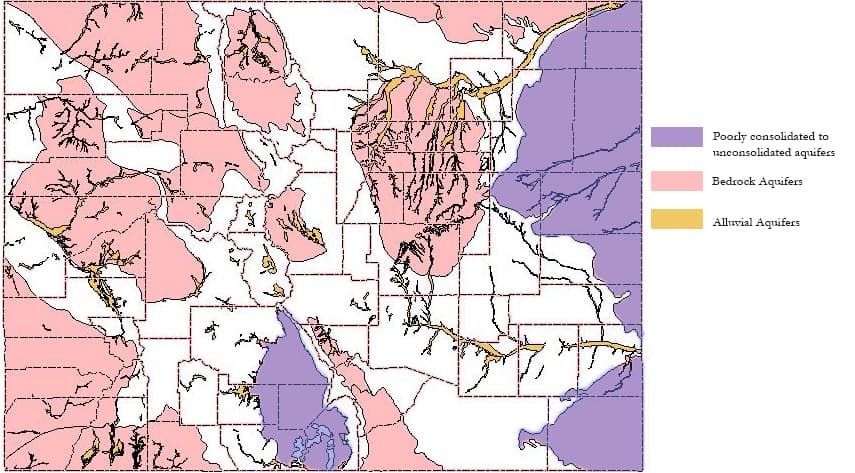

Matt Sares/CGS: Generally in southeast Colorado, towards the southeastern corner of that area, we're looking at primarily the High Plains aquifer. Some people call it the Ogallala aquifer. Then beneath that, you get into bedrock sedimentary aquifers, such as the Dakota formation, the Cheyenne formation. Those are both sandstones and there's also the Dockum formation, which is deeper, also a sandstone.

La Junta to the east side of the the Wet Mountains

Then if you move a little bit to the west, say between La Junta and the Wetmore area, east of the Wet Mountains, you get into an area where it's predominantly bedrock aquifers. There's the Fort Hays Limestone, which is sometimes very shallow and dry, but oftentimes if it's a little bit deeper, it'll be wet and we'll transmit water. Above the Fort Hays, there's Pierre Shale, which generally is difficult to get water out of. You can have hundreds, even thousands of feet of that Pierre Shale before you hit an aquifer, and that's going to be a really difficult area to find water.

Mountains including the Front Range, Sangre de Cristos and Collegiates

Lesley Sebol/CGS: It's granite bedrock. The granites are considered the basement rock. That's the lowest most comprehensive unit, and through faulting and plate tectonics, they've been lifted up and so along the Front Range here, the granites are exposed. That same granite goes down underneath the Plains and is quite deep, and I think the deepest is about 15,000 feet near Kiowa (east of Castle Rock), so it's pretty deep.

But along the Front Range and in the other mountains, the granites are exposed, so when you put a well in those, you're tapping directly into the granite and you're relying on the fractures in the granite to yield the water.

Wet Mountain Valley

Matt Sares/CGS: As you go into the Wet Mountain Valley, on the west side of the Wet Mountains, there's alluvial sediments, so those surface gravels and sands that are laid down by rivers and they stay relatively saturated, that's a good resource of water in the Wet Mountain Valley, but you might not actually be in an area where there is that alluvial material exists. So then again, you're going to be looking at bedrock and there are many different types of rock in the Wet Mountain Valley, and so it's very individualized in terms of where you are or what those aquifers are going to be below you.

Upper Arkansas River Valley and Chaffee County

Lesley Sebol/CGS: The Dry Union Formation is sediment that came off of the uplifting mountains that filled essentially the valley in between. The Dry Union can be thousands of feet thick in the center. It's a limited supply in the long term, but in the short term, people do have wells in it.

Denver Basin

Matt Sares/CGS:Then moving from that area to say the Colorado Springs area where you're in the Denver basin, again, you can have stream gravels. Below that, you're going to have the sedimentary rocks of the Denver basin.

San Luis Valley

Matt Sares/CGS: The San Luis Valley is a very different aquifer system. In geologic history, there was a lake in the area of the San Luis basin. When that lake was in place, a lot of fine sediments accumulated and created an aquitard or a confining unit, and then above that sediments off of the San de Cristos and the San Juans were shed on top of those fine sediments. After the lake had drained below that confining unit that was laid down by lake clays, you have the confined aquifer, and above that you have the unconfined aquifer. The confined aquifer has been dropping for many years now, and during the drought after 2002 and later it accelerated.

Lesley Sebol, Colorado Geological Survey Hydrogeologist

Matt Sares, Colorado Geological Survey Hydrogeologist

Additionally the Upper Black Squirrel Creek alluvial aquifer is located east of Colorado Springs and Raton basin alluvial and bedrock aquifers are in the Purgatorie River and Apishipa River area that extends south of Walsenburg and La Veta into the Trinidad area and into Northern New Mexico.

Editors Note: This story has been updated to correct typographical errors in several of the terms and proper names for the geological formations and in the captions of the sources' photographs.

- Finding underground water from 100 feet up in the air: How aerial sensing systems chart El Paso County's natural resources

- Many people on the Front Range depend on water from the Denver Basin. But the underground supply isn't infinite

- Study offering free well testing for homeowners in Otero, Bent, Prowers and Kiowa counties for certain contaminants

- Want to drill a well for your home? Some rules in Colorado might surprise you