Former Gov. John Hickenlooper cast himself as the “pragmatic’’ candidate in the 2020 Democratic Senate primary. Even as he has touted his experience and record he’s had to defend himself from a handful of missteps that have dogged him recently.

Hickenlooper argues his experience as an executive and business owner will serve the state better than someone who’s been a legislator. “They create these flourishes and these visions of what they can do,” he said.

“But once you've implemented large programs, like when we implemented the Affordable Care Act … you see it from a different perspective. And one of the things I want to — I really am excited about doing in Washington is being able to address how legislation in Washington affects states and affects cities and municipalities.”

His opponent in the June 30 primary, former Colorado House Speaker Andrew Romanoff, casts himself as the progressive at a time of major change in the country. Notably, Romanoff has wrapped himself in the banner for Medicare For All, an option that doesn’t interest Hickenlooper.

“Great transformations in American history are generally done by giving Americans choices, not forcing them to accept a different solution than what they, what they're accustomed to,” Hickenlooper said.

After two terms as mayor of Denver and then two as governor, Hickenlooper entered the race as a strong favorite. Since the start of June, though, he’s been on the defensive. He’s had to walk back several statements about race and faced controversy over his ethics during his time as the governor. The outcome of that was a fine by the Colorado Independent Ethics Commission for two violations of the state ban on accepting valuable gifts. The commission also cited him for contempt for skipping the first day of a hearing into the complaints.

“I take responsibility for these violations,” he told CPR’s Colorado Matters. “We did everything we could, any mistakes were inadvertent, they were unintentional.”

The candidate that both Hickenlooper and Romanoff want to unseat, incumbent Republican Sen. Cory Gardner latched on to the flap with the ethics board in a campaign ad targeted at the former governor.

Interview Highlights

On whether his climate change plan moves too slowly:

“Certainly we've got to have a fierce urgency … I believe that what we are proposing is pragmatic and practical. And my experience as a small business person where you can't just build as big a restaurant as you want, you can't just have as big a kitchen in that restaurant as you want. You have to figure out what works.”

On that time he drank fracking fluid:

Jocelyn Mullen of Grand Junction asked: “I'd like to know how he justifies drinking food-grade fracking fluid, to assure all of us that fracking is safe. He lost my respect that day (ed note: this happened in 2013). I need to understand his thought process. Does he not think we're intelligent enough to see through that? If all fracking fluid were food-grade, there wouldn't be a problem. Please justify your actions, Governor. Thank you.

Hickenlooper: “I was trying to get to A) a point that they reveal what the ingredients were in frac fluid, and that's when they produced this food-grade frac fluid. But really I wanted to get to the point where they would agree to negotiate for regulations prohibiting fugitive emissions, right? Fugitive emissions is when they vent methane or any of these oxides from tanks or pipes or batteries or leaks and no state had ever been able to get the oil and gas industry to agree to regulate fugitive emissions.

“And they didn't trust me. They thought I was a puppet of the, those lefty environmentalists. And when he (an industry executive) took the sip of this stuff, they were either going to trust me or not. That was the reason. I wasn't trying to show how safe fracking fluid was. I've got a master's in earth and environmental science. I understand the difference.”

- Amid Protests In Colorado, Democratic U.S. Senate Candidates Explain Where They Stand On Race

- US Senate Candidate Andrew Romanoff Imagines A Climate Change-Ravaged Hellscape In A New Ad. Is That Good Politics?

- National Climate Activists Kick Off US Senate Effort By Trying To Take Down Hickenlooper

- Hickenlooper Releases 1st TV Ad As Romanoff Releases Video On Social Media

- Gardner Leads The 2020 Colorado Senate Race In Cash

- What Is John Hickenlooper’s Ethics Complaint About?

On how he’d promote racial equity as a senator:

“What about the issues around the systemic inequity in housing or in health care, the systemic inequity in education and education outcomes and in jobs, just opportunity?

This country was founded under the concept of perhaps alone in the world that all people are equal and all people are created equal. And we have not lived up to that. And I think we're at a point now where we can begin to look at what are the specific things you do in terms of making sure that there is equity in housing, and where are they, how many vouchers do you need? What kind of subsidies do you need for affordable housing and what are the simultaneous ways that you can increase the earnings of African American workers?”

On the public option for health care:

“The public option done properly and that means it's a sliding scale, it's maybe a combination of Medicare and Medicare advantage, or maybe even some parts of Medicaid, but it's a public option that will be sufficiently attractive, that people will be able to afford it and will be able to use it and will allow us to, you know, finally in this country get to universal coverage.”

Read The Transcript

Ryan Warner: This is Colorado Matters from CPR News. I'm Ryan Warner. We chose a day in former governor, John Hickenlooper's life to get a sense of his campaign for the U. S. Senate. He's running against former State House Speaker Andrew Romanoff in this month's Democratic primary. We chose to highlight June 12th, in part because the Hickenlooper campaign invited us to drop in on a town hall that day about public lands. In the end, the day wound up being more of a rollercoaster than a campaign might want. It is the morning of the 12th, and you can still feel the afterburn of a TV news report from the night before.

(pre-recorded segment)

Newscaster: Just days after a deadly explosion in Firestone was tied to a leaking underground pipeline, Anadarko Oil and Gas, the company that owned the line wrote a $25,000 check to the office of then-Gov. John Hickenlooper.

RW: It's an especially fraught time for a story about corporate coziness to break because later this same day, the state's Independent Ethics Commission will decide how much to find Mr. Hickenlooper for two violations of the state's gift ban. But first, the campaign event, the centerpiece of Hickenlooper's schedule. The event is virtual, of course, that's the nature of pandemic politicking. Video chatting from indoors, even when the topic is the outdoors.

John Hickenlooper: Appreciate all of you being here today. And while I really wish I could be together with you out there enjoying our public lands, I'm glad we can do this virtually and keep everyone safe. We need to flip the Senate and beat Donald Trump to finally pass the CORE Act and stop all these attacks on public lands. Our President Trump and Senator Gardner have overseen the largest rollback of protected public lands in the history of this country.

RW: Joining the forum, the man Hickenlooper hopes to work alongside in the U.S. Senate, Michael Bennet. If Hickenlooper wins the primary, then the general, it won't be the first time they worked side by side. Bennet was his chief of staff as Denver mayor.

Michael Bennet: When I think about the prospect, the possibility that we could end up with two Democratic senators from New Mexico, two Democratic senators from Colorado, two Democratic senators from Montana, two Democratic senators from Arizona, two Democratic senators from Nevada -- all of whom not only have public lands as a huge priority, but addressing climate change is a huge priority. You can really begin to see the potential for an incredible amount of change to happen in the Senate and the House. And with a new president.

RW: You heard a reference earlier to the CORE Act, a comprehensive public lands bill that has stalled in Congress with no support from the other side of the aisle. Much of the virtual campaign event is spent pondering why many local Republican leaders embrace the legislation while those in D.C. are unmoved. Well, it's approaching one o'clock, this video conference winds down, but an arguably more consequential one is getting underway.

Ethics Commissioner: And one of the issues we've had in the commission for a long time is we worry about being used by complainants and respondents alike for political purposes and so...

RW: A meeting of Colorado's Independent Ethics Commission.

Commission Voice 1: Commission has always been on guard about, is to not be bound by tactical decisions of the parties...

RW: The commissioners are deciding how much to fine Hickenlooper for accepting gifts he shouldn't have while he was governor; a flight to Connecticut on a private jet, a fancy car ride during a conference in Europe.

Commission Chair Elizabeth Krupa: Just to clarify, the vote is for $550, correct?

Commission Voice 2: My understanding, Madam Chair, is that this is $275 doubled for a total of $550.

Chair Elizabeth Krupa: Yes.

Commission Voice 2: OK. Commissioner Johnson.

Commissioner Johnson: Yes.

Commission Voice 2: Commissioner Willett.

Commissioner Willett: Yes.

Commission Voice 2: Commissioner Leone.

Commissioner Leone: Yes.

Commission Voice 2: Madam chair.

Chair Elizabeth Krupa: No.

RW: All told they levy $2,750 in fines. They do not fine Hickenlooper for being a no show to an earlier hearing for which they held him in contempt.

Chair Elizabeth Krupa: Thank you. And I think that concludes our deliberations and I want to thank the commissioners for their time and the parties that would conclude I believe the Hickenlooper matter and the deliberations that the commission had to do. So, thank you very much.

(live interview segment begins)

RW: Some of the ups and downs in the course of a single day as former Governor John Hickenlooper campaigns for Senate with deeper pockets and deeper national party support than his primary rival, Andrew Romanoff. You can hear my in-depth discussion with Mr. Romanoff at cpr.org. Today, it's Mr. Hickenlooper, who joined me in the studio at a safe distance across our round table. Governor, welcome back to the program.

John Hickenlooper: Thanks.

RW: I'd like to start with climate change, which you've said that dealing with is a top priority. Your stated goal is to get to a hundred percent renewable energy with net zero emissions by 2050. What do you see as the biggest obstacle to achieving that?

JH: Well, like any big goal, the, you've got to get people to believe that you can do it. You've got to have a credible pathway, but obviously there's gotta be a transition to electric vehicles. Part of why we took our Volkswagen fraud money or a significant chunk of it to work with other Western states to create the foundations for a network of rapid recharging stations for electric vehicles.

We've also got to stop using coal for, to generate electricity. And again, a great model we did here in Colorado, closing the two coal plants down in Pueblo, replacing them with wind solar and batteries. So that is where you get market forces where people can get, can put in new facilities and have clean air, clean water, and they save money at the same time. But we also just, let me, I'm sorry. I'm taking too long.

RW: Well, no.

JH: I'm out of practice.

RW: I think the reason I was interjecting is you said the first obstacle is convincing people it's necessary and possible.

JH: Right.

RW: Is that convincing Republicans, is that convincing -- who's that convincing?

JH: There was a long, hundreds of millions of dollars campaign of disinformation saying that climate change was a hoax, climate change wasn't real. Whereas the vast majority of scientists agree that it is very real, a significant threat to the future of our planet and largely caused by the activities of mankind. So that's the first challenge because we've got to recognize, and again, the large oil companies are no longer funding that disinformation. And I think we're at a moment where we can begin to make real progress in letting people see a future where they can address climate change. And it's not going to be the end of the economy. It's not going to be, you know, we're not going to spend trillions of dollars and lose millions of jobs.

We do have challenges in industry. You know, concrete is a very widely used basic component of almost all of our, everything we do. And it gives off, in the process of creating concrete and then as it cures, it gives off a lot of CO2. There are ways we can innovate and find better ways of building things. Concrete's always been so easy and available that, that people haven't had a motivation, but there are a bunch of things in industry like that where we have to innovate. Same thing in agriculture. So that innovation, what I argue is that the innovation is going to create not just jobs, but whole new professions. And we're going to create many, many more jobs than are going to be lost in the transition. And in many ways, those new professions are going to transform other industries as well. Just like just like aerospace industry did 50 years ago,

RW: Your opponent, Mr. Romanoff says these goals can be reached faster. His plan would cut in half the total greenhouse gas emissions from all sectors by 2030, replace fossil fuels with clean energy to meet electrical needs by 2035 and reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2040. He favors The Green New Deal, which speaking of jobs, the outline of The Green New Deal would guarantee jobs to Americans who want them. If, as you describe, climate change is the defining issue of our time, why not push for these faster goals?

JH: Well, what I say is 2050 at the absolute latest, if we can get to 2045, 2040, you know, I've got a master's in earth and environmental science, so I spent a fair amount of time -- back then we called it, we didn't call it climate change, we called it the greenhouse effect, but we knew it was a real threat. There has been a huge amount of research in looking at what are the stages and the steps that we need to go through to get to a net zero economy in terms of how we use energy.

But certainly, we've got to have a fierce urgency, we've got to do everything we can and not just in the United States, us getting to net-zero just by ourselves, if we can't bring the rest of the world with us, it'll be a pretty hollow victory.

RW: Okay. So, speak to the primary voter who says, one guy wants to do this by 2050, one guy wants to do it considerably faster. I'm voting for that guy.

JH: Yeah, well, that's, that is the challenge. I believe that what we are proposing is pragmatic and practical. And my experience as a small business person where you can't just build as big a restaurant as you want, you can't just have as big a kitchen in that restaurant as you want. You have to figure out what works. And I think what we need in Washington is maybe not another great legislator. Obviously, legislators have become incredibly good at attacking the other side or their opponent in a primary. And they also have these, they create these flourishes and these visions of what they can do.

But once you've implemented large programs, like when we implemented the Affordable Care Act is, would be one example. You really get into the granularity that the, the weeds of the process and you see it from a different perspective. And one of the things I want to, I really am excited about doing in Washington is being able to address how legislation in Washington affects states and affects cities and municipalities.

RW: In February of 2013, you testified before a U.S. Senate panel and revealed that you'd sat around with oil executives and you'd taken a swig of fracking fluid. Listener Jocelyn Mullen of Grand Junction has a question for you about that.

Jocelyn Mullin: I'd like to know how he justifies drinking food-grade fracking fluid, to assure all of us that fracking is safe. He lost my respect that day. I need to understand his thought process. Does he not think we're intelligent enough to see through that? If all fracking fluid were food-grade, there wouldn't be a problem. Please justify your actions, Governor. Thank you.

JH: Thank you. And I appreciate the question. What I was doing in that, I was trying to get to A) a point that they reveal what the ingredients were in frac fluid, and that's when they produced this food-grade frac fluid. But really, I wanted to get to the point where they would agree to negotiate for regulations prohibiting fugitive emissions, right? Fugitive emissions is when they vent methane or any of these oxides from tanks or pipes or batteries or leaks and no state had ever been able to get the oil and gas industry to agree to regulate fugitive emissions. And they didn't trust me. They thought I was a puppet of the, the, those lefty environmentalists. And when he took the sip of this stuff, they were either going to trust me or not. That was the reason. I wasn't trying to show how safe fracking fluid was. I've got a master's in earth and environmental science. I understand the difference. What I was trying...

RW: Wasn't that the impression that it gave?

JH: It did. And I tried in every way I could to dispel it, but sometimes these myths get going. I think what's important is that sixteen months later, we had the first methane regulations in America.

RW: You were saying that the oil execs thought you were kind of lefty, and yet your critics on the left have called you Frackenlooper. And they say that you favor the oil and gas industry over a green economy. That reputation might've been bolstered by this recent investigation from CBS4 and the Colorado Sun, which found that several Colorado governors have accepted private donations to the state to fund programs and employees in their administrations. So, it is a practice that started before you and continues, by the way, in the Polis administration. But in your case, a significant amount of money, at least $325,000 in your second term came from the oil and gas industry. Some of it from Anadarko just weeks after an explosion killed two people at a house in Firestone and officials later traced that back to an Anadarko well. Does that indicate that the industry has some influence over you?

JH: No, of course not. I'm the one that got them to agree to methane regulations. They spend $60 million a year on that. I don't know what Anadarko's part is. We, our community partnerships which received this money, was run completely separate from the governor's office. They didn't ask me to make calls. They didn't tell me when someone gave money. These public-private partnerships are what you use when you're in lean times to maintain programs, you think are important for the people of Colorado.

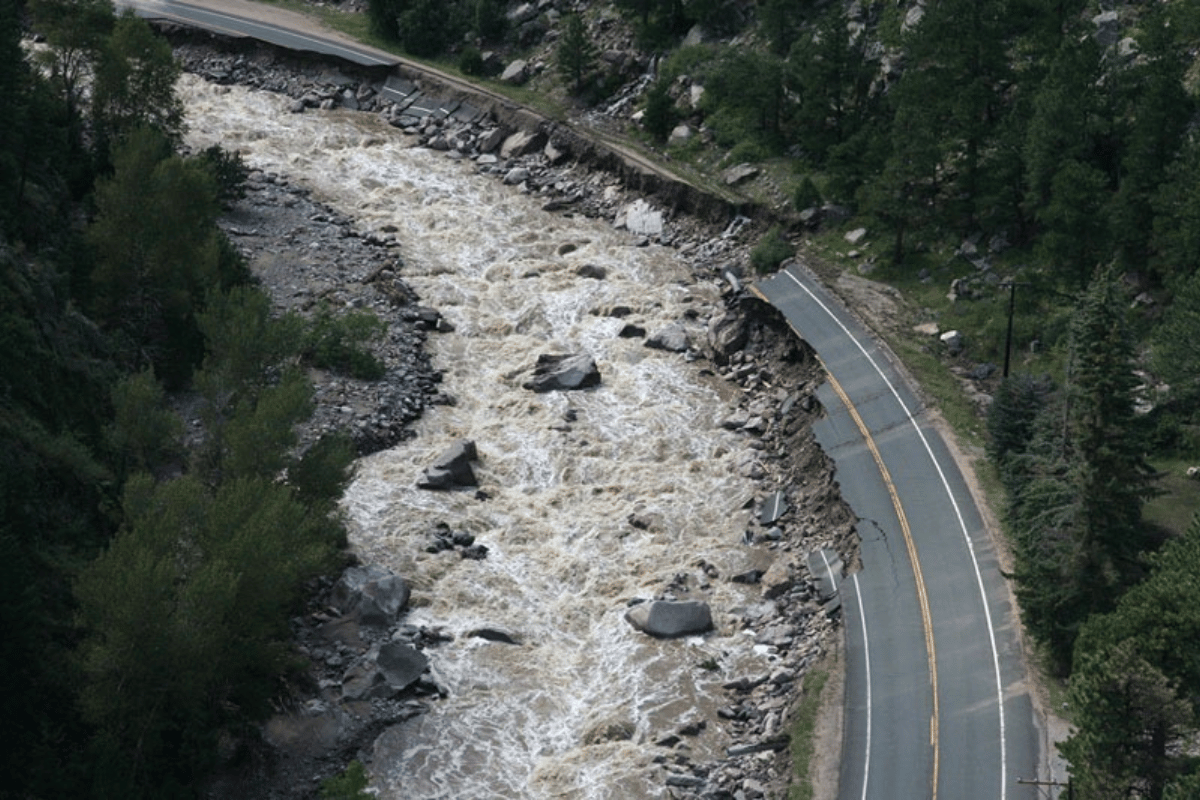

So, One Book One Colorado, you know, making sure that we provided 450,000 four-year-old kids, for many of them the first book that they'd ever owned. You know, when we had the flood in 2013, we raised millions of dollars from corporate generosity. We didn't know who, we didn't go out and ask them. We didn't know who it was, but we knew that people had lost almost everything and we had to do everything we could to rebuild them, but we made sure that every donation was on the programs, was in some sort of a news release somewhere, maybe not perfect, but we took that transparency to a new level.

RW: I'd like to talk about healthcare. This is another area where you and Mr. Romanoff are fairly far apart. So, Romanoff wants Medicare For All, you call for a public option that would ultimately get the country to universal coverage. I want to note that millions of people across the country have been thrown out of work by the COVID-19 pandemic. And Mr. Romanoff says that proves people can't rely on employers right now to provide them with insurance.

Andrew Romanoff: When not only 28 million Americans are uninsured and 44 million are under- insured, but when as many as 43 million more Americans may lose their employer-based coverage because of this downturn, surely that's a time for us to say your health insurance should not depend on your job.

RW: He thinks this is the time to scrap employer-based health coverage. Presumably by building on the Affordable Care Act, you'd keep that in place. Is this the time in place for that?

JH: Well we just don't agree. You know, Barack Obama created the Affordable Care Act, a transformational moment. You know, Andrew wants to discard it, just scrape it off and start all over again.

RW: I mean, Medicare exists.

JH: Sure. But not in the scale that again, you'd have to scrap all the other of the Affordable Care Act. And, and, and again, people's private insurance, whether they want to lose it or not. Great transformations in American history are generally done by giving Americans choices, not forcing them to accept a different solution than what they, what they're accustomed to. And I think that's the challenge here. I don't think we should scrape away and discard what Barack Obama created. I think we should build on it as a foundation.

RW: So, would the public option mean that no one is uninsured?

JH: Yes. It would allow us to get to universal coverage, I think much more rapidly. And you know, the people that lost their insurance in the COVID-19 pandemic, if they're out of work, they go immediately into Medicaid. So, there's a relatively smooth transition possible to make sure that in this system, people have constant coverage. The public option done properly and that means it's a sliding scale, it's maybe a combination of Medicare and Medicare advantage, or maybe even some parts of Medicaid, but it's a public option that will be sufficiently attractive, that people will be able to afford it and will be able to use it and will allow us to, you know, finally in this country get to universal coverage.

RW: I mean, it sounds so easy and breezy and reasonable, one wonders why it hasn't happened yet.

JH: Well, I can explain that to you. Okay. There's a political party that was so adamantly opposed to the Affordable Care Act that they proclaimed publicly, and Mitch McConnell has said this many times and Cory Gardner supports it, that they want nothing to do with improving the Affordable Care Act. They will only be satisfied if it is, you know, the, if their lawsuit succeeds and it goes to the trash bins of history. And I think that function that they're trying to achieve, the lawsuit that Cory Gardner supports by eliminating the Affordable Care Act, and they really don't have anything to take its place. In Colorado they tell me it's 2.4 million people have pre-existing medical conditions that would lose their protections if the Affordable Care Act went away. Why aren't more people talking about that?

RW: I'd like to talk about the ethics case that was against you. The state's Independent Ethics Commission found that you twice violated Colorado's ban on accepting valuable gifts while you were in office. Once on a trip to commission a submarine named after Colorado. Another time at a conference in Europe. You were fined $2,750. But at least as big a point of contention was that you skipped the first day of the hearing. And the commission found you in contempt. At one point, Mr. Romanoff suggested you drop out of the race because of this. Did you ever consider dropping out after the Ethics...

JH: No.

RW: Commission finished its work. Did it give you pause? Like maybe I'm too bruised or too damaged to move forward?

JH: No, this is an example of what politics in Washington has become. And it's clearly coming out to Colorado in this cycle. We're talking about trips I took when I was governor of Colorado, literally I said I would fly anywhere and everywhere to try and rebuild Colorado's economy. We were 40th in job creation when I started. And I literally went everywhere to talk about the Colorado Way and how we did things better and we could collaborate and we were a great place to open an office. So one trip was to a conference. It was a long way away, so I didn't want to have even the appearance of misconduct. So I paid my own airfare. I paid what I was told were all the costs of the conference, the hotel, the, the meals. Evidently there was a sponsor and so ground transportation and maybe a couple of meals weren't covered. Somehow, I, you know, I didn't know about that. The, the, my team, we have lawyers and schedulers who look at every time I traveled to make sure that it conforms with all the ethics criteria as we know them. So that was one violation.

And then the second one was a violation of going to, as you say, the USS Colorado in Connecticut, I went on the plane of the, the foundation of the board members of the company and the foundation that were helping create the ceremony and actually make sure that Colorado was supporting the sailors on this new submarine. Again, I take responsibility for these violations, but these allegations came from a dark money Republican organization, and we were found in violation of two relatively minor. I mean...

RW: Let me just say some of the claims against you had expired because of the statute of limitations. I mean, the commission found that you violated the gifts ban twice, they dismissed four other trips included in the complaint. You know, the Commissioner, Bill Leone, whom you appointed, he voted to find you in violation. What if it could be clear? And he said, quoting here, "If we allow these kind of special privately financed treatment for elected officials, it just kind of accentuates the cynicism", speaking there, about voter cynicism about politics. Do you, do you fear that this increases cynicism?

JH: Well, I certainly think that the way it's being weaponized by the Republicans will increase cynicism, but that's just where our politics has come from, or has come to. We did everything we could, any mistakes were inadvertent, they were unintentional.

RW: I do want to talk about policing, which is under an intense spotlight after the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. When you were Denver mayor, you adopted what's called broken windows policing. It's the idea that even minor criminal activity, like a broken window leads to other more serious crimes and the police should crack down on small violations. At the time researchers, some of them were skeptical. Now critics say it has increased incarceration rates in minority communities; that it didn't really cut down on crime. Do you regret broken windows?

JH: Well, it was an experiment, a brief experiment, you know, when, when Paul Childs got shot. And if you'll remember, Paul Childs was a 15-year-old African American teenager who was shot in his own front hall two weeks before I got inaugurated. And I went to his funeral with Mayor Webb, my predecessor, and his wife Wilma, and I met some of the Black Ministerial Alliance, an alliance of roughly 35 black pastors, and I needed their help to address what clearly was unacceptable. This was, you know, this wasn't the first police shooting we had that year.

And we began a process over eighteen months of major police reform. This is ten years before Ferguson, where we create an officer of an independent monitor, with subpoena powers to investigate any allegation of police brutality. We had to create a civilian oversight commission to make sure that the community could decide and have a loud voice in how their neighborhood was policed. We went to every single police officer and gave them CIT training, Crisis Intervention and De-escalation Training so that they were trained on how to talk their way down from confrontations. There's a whole long list of what we did. And I'm the first to say, we didn't go far enough.

RW: Was broken windows misguided.

JH: You know, I don't think it was successful as, or, or catastrophic. In other words, I haven't gone back and looked at the data, but my memory of it was that we were trying to find ways to engage the community in the safety of their own neighborhoods. We looked at everything. This was a time when we were trying to make our community safer, but also recognizing that we had real issues between the police department and the black community and the Latino community.

RW: I do want to talk about racial equity, noting that you've been criticized for your remarks about race at a forum in May, you were asked what the term Black Lives Matter means to you and you responded that it means Every Life Matters. You've since said, you tripped on your words then in the debate you referred to the shooting of George Floyd, and you have apologized for old video of you that emerged comparing the life of a politician to that of a slave. It's something you said in the debate that CPR sponsored this week that I want to pick up on, though, that amidst the protests. You had a realization quote, "I felt that I just hadn't done enough that I hadn't pushed myself and my team to get as much done as we should have." So, what is a step you'd take towards racial equity as a U.S. Senator?

JH: The media has been very focused on the police brutality and that's part of what I was referring to. You know, we made one of the original efforts to dramatically reduce the use of strangle holds, choke holds. But now we realize we probably should have just eliminated it. We changed the discipline matrix, how police could be punished so that even their first violation, if they lie about an incident, they could be fired. We were never able to do that before. We did all those things, but clearly, we didn't go far enough. But what about the issues around the systemic inequity in housing or in healthcare, the systemic inequity in education and education outcomes and in jobs, just opportunity.

This country was founded under the, the concept of perhaps alone in the world that all people are equal and all people are created equal. And we have not lived up to that. And I think we're at a point now where we can begin to look at what are the specific things you do in terms of making sure that there is equity in housing, and where are the, how many vouchers do you need? What kind of subsidies do you need for affordable housing and what are the, the simultaneous ways that you can increase the earnings of African American workers?

RW: Mr. Hickenlooper, there have been ways you've talked about the Senate race, the Senate seat before you actually joined the race that didn't paint the job in the greatest light for you. You said that it wasn't necessarily a job you wanted in various ways, or that you'd derive much joy from. And it just occurred to me that you ran restaurants for a long time. And I just want you to imagine that you were hiring a front of house manager, right? And there were two candidates for the job. One of whom has said in the past, I don't really want this job. It doesn't fit me. I don't think I'd be good at it. And then there's a candidate who goes, I love that job. That's the job I want. Wouldn't you as a restaurant owner, go with the guy who had never professed he didn't want the job.

JH: That person who had not wanted the job would have to convince me that they had changed and they'd have to have a compelling argument. And my argument is that I did bad mouth Washington as a broken place. The Senate was a place where good ideas go, go to die. But as I, as I reflected and discussed with my, with my wife and my neighbors, old friends, it was pointed out to me, I called a number of former governors, who'd gone on to become senators. I talked to some small business owners who'd gone into the Senate. I mean, they're only, they're only five or six people in the Senate now who've ever had any small business experience. That's probably at a historic low.

It's the same skills. What I was, if I was a restaurant owner and this person who said they weren't cut out for the job was going to explain why they were the best, I'd want to hear them say, what are the skills they've got. When I came in as mayor and I got all 34 mayors unanimously to support FasTracks, right?

RW: The transportation program in Metro Denver.

JH: Well, one of the most ambitious transit initiatives in modern American history, and the only time in modern American history where our metropolitan region got all 34 mayors, Republicans and Democrats to support a tax increase. That ability to get people who don't like each other and I changed that. And to this day, we have agreements that you can't poach, you know, offer incentives to take a business from one municipality to another. That's what they need in Washington. They don't need another person to go in and yell at the other side, or to have wonderful rosy speeches about what we're going to do. They need someone who's got a clear track record of bringing people together, finding common ground, making decisions that lead to solutions and moving on to the next project.

RW: Okay. In the last few minutes here, when Andrew Romanoff was on the show, we heard from someone who endorsed you and we presented that to Mr. Romanoff. So we'll do the same with you. I rang up former state lawmaker, Joe Salazar. He has endorsed Romanoff. I asked him why he didn't sign on to your campaign.

Joe Salazar: Well, I think it's about time that we have elected officials or those who are running for office provide clarity in terms of how they're going to represent us in either federal, state or local government. And one thing that Hickenlooper does all the time is he hedges his bets and he doesn't provide any clarity to community about anything.

RW: What do you say to someone who thinks you're wishy washy, that you test the waters a lot before you make a decision?

JH: Well, I certainly listen to on, on difficult decisions, I listen to a lot of people. I think that's a good thing. What I would argue is if you go down, go to our website, if you want to look and see the specifics of how we're going to address climate change, there's a lot more detail on our website than there is on Andrew's. If you want to look at, at healthcare, I believe we can get a lot faster. We can get to universal coverage, a lot faster through a public option than we ever could discarding everything that Barack Obama built just, you know, getting rid of it. And then starting from scratch. These are specific details about major issues where I can support the details of what is being asked.

So, I understand that it took me a long time to make up my mind about the death penalty. No question about it. It was a difficult decision and I did talk to a lot of people, but I didn't spin out the appeals processor or go beyond the time that had been allotted before I had to make that decision. I made the decision in the appropriate amount of time. And I think I made the right decision. The state now recognizes and most polling shows that people recognize that the death penalty is unfair. Oftentimes, you know, the wrong person gets found guilty and sentenced to die. It's long overdue to be, to be repealed.

RW: And it wasn't until the next administration that it was repealed.

JH: That's true. But that's the point of the process. I took the hard stand and started a statewide discussion. This is a big decision but we got to the right decision and in that process, we changed public sentiment. We had to build public sentiment and we did that and now we have a solution that the state can respect and it's not going to be a pendulum going back and forth.

RW: Thank you so much for being with us.

JH: Always a pleasure.