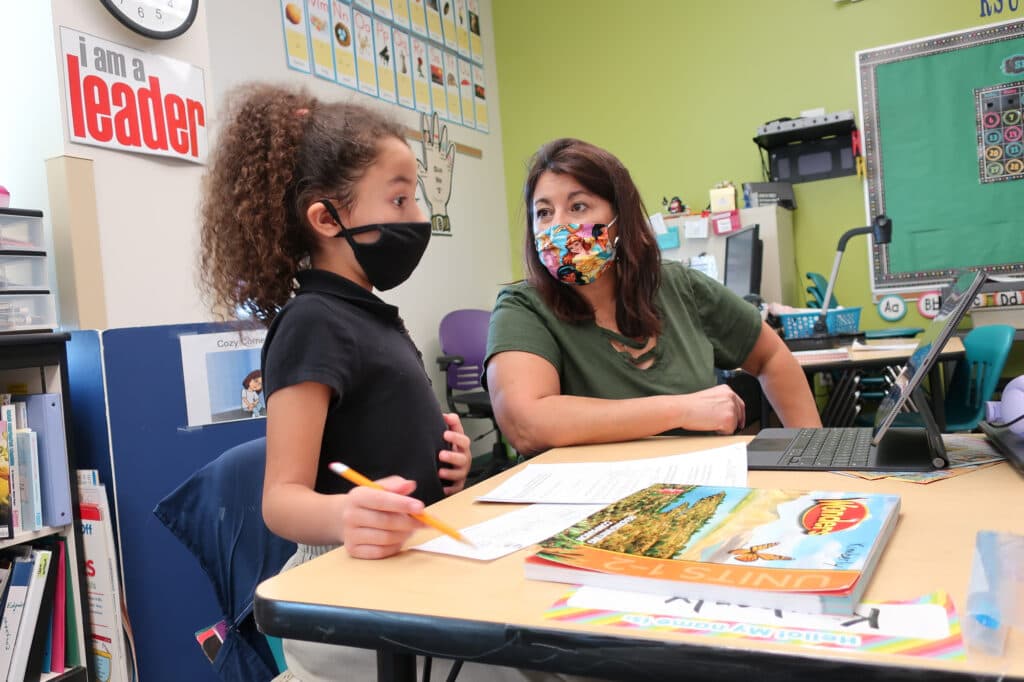

This is a continuing series on one of the first classrooms to go back to in-person learning – Renea Sutton’s Level 3 classroom, Room 132, at Josephine Hodgkins Leadership Academy in Westminster Public Schools.

The year of COVID-19 presents herculean challenges for schools.

But for teacher Renea Sutton in room 132 in Josephine Hodgkins Leadership Academy, it presents big opportunities to teach kids how to move forward when things aren’t easy. She’s had to create a community even when everyone’s wearing a mask and stays an arm’s length apart, squeeze in extra time to learn computer skills in case her class has to pivot to remote learning, and integrate new students into her classroom as they trickle in from virtual learning.

“Change is very hard,” she said. “There are people who like to know the end, like ‘This is how it's going to go.’ And you can't this year. That’s out the window.”

Students are getting back in the swing of learning after five months out of the classroom, from math equations to writing paragraphs with proper indentation. But the pandemic still promises to bring tumult to the classroom, starting with recess.

There’s a big fat problem sitting in front of Sebastian.

The 8-year-old sits next to me under a tree. I ask him why he doesn’t go join the other kids who are running around in the field, where there are no soccer balls or footballs to be found.

“Well, it’s just that since there’s nothing to play with out on the field, there’s nothing to do,” he said with a world weariness beyond his years.

Here’s an 8-year-old who has been sitting at home since March and now, finally, with a green field stretched out in front of him, kids bursting with energy all around him, there are no balls to play with. It’s like getting a bicycle with flat tires.

This issue is a big sore spot with the students of Room 132, another sign that things aren’t back to normal. Another set of kids is on the playground, using the slides, swings and monkey bars, and Room 132 is stuck with the field.

“We never get on the playground!” shouts Jordynn. “We’ve been on the field for four days!”

“Four days and I want to get on the playground,” says pig-tailed Balentina, angrily. “I can’t because…because….we can’t.”

It seems like we’re headed for a full-scale third-grade rebellion.

“It’s just weird,” says Sebastian, looking wistfully at the playground. “I want to go back to old life where all of us go on to the playground.”

Their teacher would be proud: The girls are already plotting how to solve the problem. One of Sutton’s major goals is to get kids problem-solving and advocating for themselves.

“We could rotate,” says Balentina, as the kids file back into the school from recess. “One day yes, one day no.”

Sutton is in the midst of a predicament of her own, one with big implications for the class.

She’s a little more than a month into this grand experiment of teaching in-person during a global pandemic, and she might have to leave. She has found out that her daughter who lives out of state needs surgery. There’s no one to care for her afterwards.

“Then what happens, does that put a burden on somebody else who has to now pick the slack because I have to leave?” she wonders. “You know, that piece is just so hard. I don't want to burden anybody else.”

If she had her druthers, Sutton would teach her class remotely from out of state. But that still takes a body to supervise the kids in class. Those are scarce, and so are substitute teachers. The timing at the beginning of the year isn’t the best either.

“You're just established routines with kids. You just built your community. You're just getting into the groove of things. And every teacher is different, how they do things.”

Still, she decides to go on family medical leave for four weeks to take care of her daughter. It’s like Principal Amber Sweickowski says: Teaching is what Mrs. Sutton does, it’s not who she is.

“Is it an ideal situation? No, it’s not an ideal situation. But we care for one another. When it came to the decision of what do we do with Renea’s class, her teammates stepped up — no questions asked.”

Two of her colleagues will be each taking half of Sutton’s class of 13.

On the Thursday before she leaves, at morning meeting, where kids sign up to share something about themselves, Sutton also shares.

She tells her students it wasn’t an easy decision to leave but she wants them to be leaders while she’s gone. Rowan agrees.

“Just because we’re leaders in this classroom doesn’t mean we can’t be leaders in the other classroom,” he says.

“Absolutely!” Sutton responds. “We can show we are leaders wherever we go … maybe we understand Empower (computer learning platform) a little bit better and maybe we can be those leaders to help the classes understand Empower better. You guys have a big job.”

She asks them how they feel about the change.

Like most in the class, Rowan has mixed emotions: He’s excited because he can maybe make new friends but he’s sad that Sutton will be gone.

“I like that you said you could make new friends,” Sutton responds. “It’s pretty normal to have different feelings. You can have mixed feelings but I know you guys are going to be just fine. You’re going to step up and continue to learn.”

Kids pepper her with questions: Do they need to bring their chairs into their new classrooms? Why does her daughter need surgery? Will she take a nap on the plane ride? The meeting ends and the whole class walks back to their desks, pretending to be sloths, and gets down to writing practice.

At lunch time, munching on corn dogs and chicken wings, the kids open up a little more about their teacher leaving. For the most part, they’re pretty relaxed about it, but there are some worries.

“That I won’t make new friends,” Balentina says.

A couple of students have health concerns. Monsi says she hears about positive COVID-19 tests on the news all the time.

“I don’t know if I’m going to be safe in the other classes,” she says. “What if there’s a test positive in Ms. Cornella’s class? That’s what I’m afraid of.”

Justin, with a sweet nature and bright blue-framed glasses, is new to Room 132, and he’s nervous.

“I’m not familiar with other classmates and the class I’m going in was quarantined and I don’t know if they touched anything. I feel more scared.”

It’s true, the class he’s going into is coming back from two weeks in quarantine. I explain to him that it means it’s safe now, and they’ve deep cleaned the classroom. Justin is happy he’ll know a boy in the class but worries he won’t have too many other friends. Rowan, sitting next to him, gives him some sage advice.

“I would say it’s OK to feel scared and you should just tell people your feelings to see if they can help you with anything you’re feeling scared about.”

Justin had enough of online learning and didn’t want to do it anymore. Westminster Public Schools offers both in-person and online options.

“I had a rough time with online,” he explains. “I couldn’t do any work so I just moved to in-person.”

That is something teachers are having to adapt to: incorporating new students who trickle back in from the district’s online program.

Principal Amber Swieckowski says a few weeks ago, a couple of kids a day in each class were transitioning back. She said typically either the parents felt it was safe now or they just couldn’t manage any longer having kids at home along with their own work. Enrollment has stabilized now. The school has set the maximum number of kids per classroom at 25. The new classes for Sutton’s students will have about 20 students each.

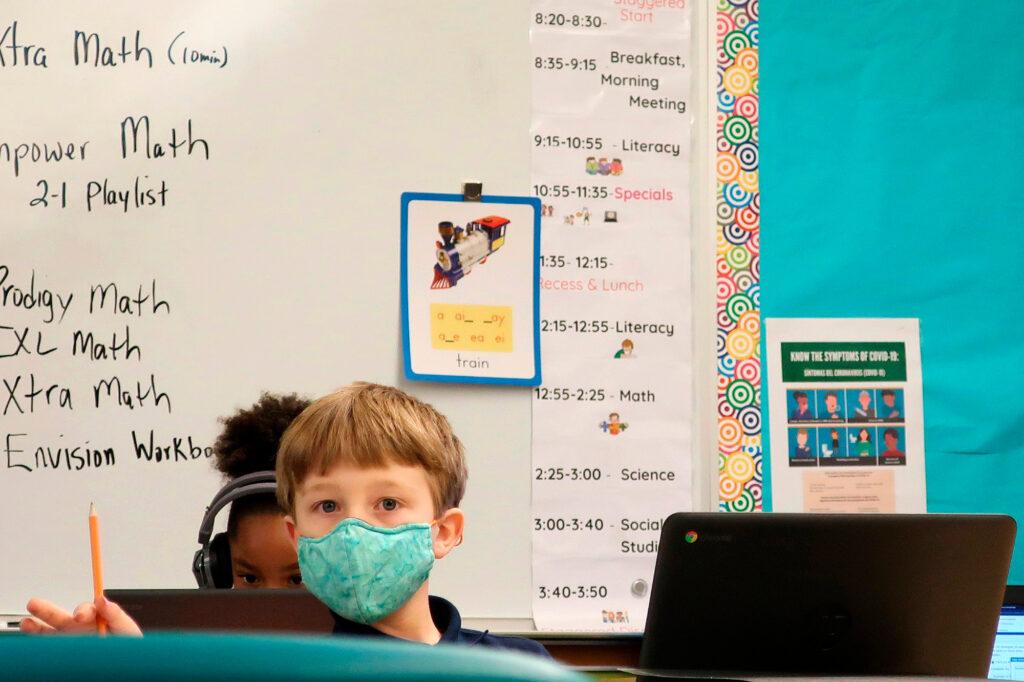

Today for math, Sutton has one online student, along with her 13 in-person students.

He’s on a laptop positioned so he can see the math work on the classroom whiteboard. Sutton begins the math lesson talking about patterns. If she has one pair of gloves, how many fingers is that?

Five, says one student quietly. Five, says another a little more loudly. Five, someone repeats.

Ten, someone finally says. That confusion cleared up, Sutton challenges the whole class to take the pattern higher.

Three pairs of gloves? Thirty! Four pairs of gloves? Forty! Five pairs of gloves? Fifty!

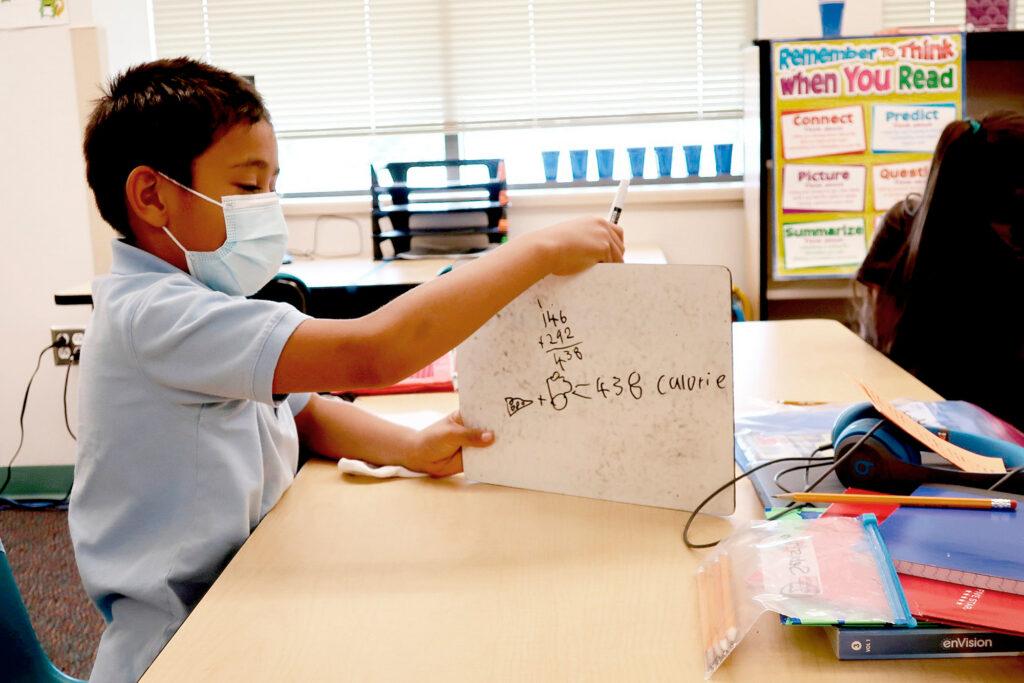

But things quickly get harder. The class is a little stumped when Sutton asks them what the word “equation” means. They’re being asked to read a chart to find the total number of calories in a slice of pizza and a cup of milk, an addition problem.

One boy starts writing all four equations for the problem — add, subtract, multiply and divide. And when the question asks students to draw a picture showing their work, some are drawing a picture of a piece of pizza and a cup of milk.

“That’s not what they’re looking for,” Sutton says. She knows some kids will need some review, like how to draw base ten blocks or group objects.

Math is going to be tough this year. There is a new curriculum that’s heavy on word problems. Word problems can hurt the brain, and, says Kimberly, other parts of the body.

“In second grade it was just so easy, and in third grade it got ...” She pauses.

“It got one step harder,” her friend Jordynn finishes her sentence.

“It got painful,” continues Kimberly, “and my arms hurt.”

By the end of the day, the class has earned a video dance break. Everyone is dancing including Sutton.

She says that doesn’t happen every year — sometimes, students hold back and she’s happy with how engaged everyone is.

“Make a pattern, make a pattern, let’s make a pattern,” the video animators sing, reinforcing the math lesson on patterns from earlier in the day. The kids sing along, shaking their hips and waving their hands.

“LOUD. LOUD. Quiet. Quiet. LOUD. LOUD. Quiet. Quiet!” they shout.

It’s been a good day, and the kids scored another victory too: They got to go on the playground.

The students took their case to Sutton, and school leaders got involved. Now there’s a daily rotating system, instead of weekly, still keeping in line with health precautions.

And when they’re on the field, they have a ball now. With COVID-19 in mind, each class must keep track of its own equipment in a mesh bag.

Then Sutton’s last day comes.

Around 3 o’clock, a visitor comes to the door: teacher Tresa Townley, who'll be taking over some of the students while Sutton is out.

“Some of you guys are going to come see me,” says Townley. Some of the kids squeal with delight.

“That’s good because we have candy for breakfast.”

It’s like someone just said the Earth is flat. There are shouts of disbelief and a bit of pandemonium.

“What! Do you believe her!!?” Sutton says. “NO!” some students respond.

Townley takes half of Room 132 into their new classroom. They choose their new desks. She explains that she does some things a little differently than Mrs. Sutton, like how she takes the kids’ temperature.

The kids troop back in Sutton’s classroom, to wrap up.

She finishes up preparing Room 132 for how things will be in the other classroom. She’s actually been getting them ready for a while now: loading up their computers with lessons that can work on if they move ahead and meeting frequently with the other teachers to ensure a smooth transition.

“Is that teacher going to do things the same way I do?” she asks them.

“No!” the kids shout.

“Probably not,” Sutton agrees.

And with that, she gives them a final goodbye. No hugs. Just air high-fives to say, “See you in four weeks.”

“Who’s ever sad that Ms. Sutton is leaving, raise your hand,” Jordynn says quietly, as she grabs her backpack and heads out the door.